9. HOW THE COMPANIES WORKED

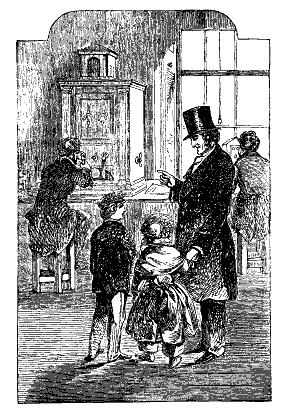

"The Telegram"

The delivery of the worst possible news to a soldier's family

by a

messenger of the Electric Telegraph Company.

Through the open window can be seen the railway station and

the telegraph wires.

A double-page, oil-print colour picture

published in the 'Illustrated London News' on February 25, 1860, from a painting by

Thomas Edward Roberts (1820-1901)

Original image courtesy of the BT Archives

The Telegraph Office

The telegraph companies in their public presence were retail concerns.

Originally they operated through their own telegraph offices at railway

stations, then eventually during the 1850s, and more often, in the high

streets of Britain's cities and towns; effectively these were all

'shops'.

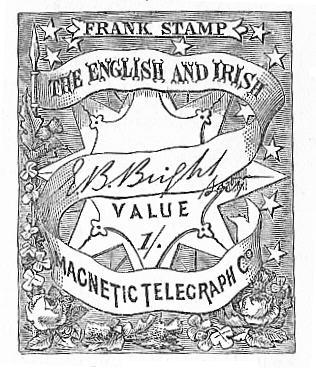

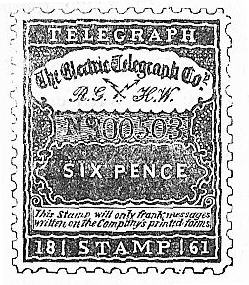

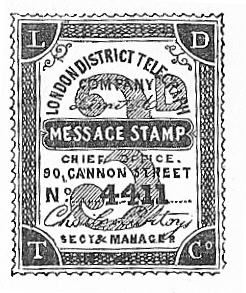

The transaction followed a common course in all of the companies. A

message, written on a form and signed by the sender, was handed in to a

telegraph office. After being pre-paid for in cash, or latterly in

telegraph stamps, the text was transmitted electrically to the nearest

station to the address in the message, where it was written down in

long-hand on another form by a clerk as received and immediately

despatched to the recipient by a foot messenger.

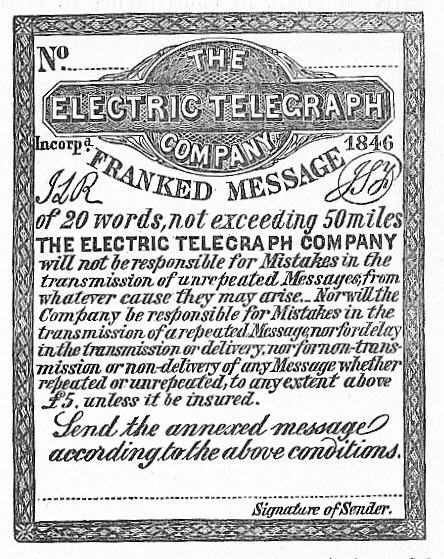

The Electric Telegraph Company sent

Telegraphic Despatches,

the early British and English & Irish companies did not give their

messages a special title, and the later British & Irish, London

District and United Kingdom companies were to use the neologism Telegram

in their businesses. The word 'telegram', originating in April 1852 in

America, began to enter the popular English vocabulary from around 1853

or 1854.

The public entered the office and handed over a

message forwarding form at

a shop counter; behind the counter were shelves with the telegraphic

instruments and the batteries of electric cells. The clerks received

the messages and worked the telegraphic instruments.

In all except the largest City offices the

instruments were visible to the public. The needle instruments were

large; contained in handsome pieces of glass- fronted cabinet-work, the

bodies mainly in mahogany or oak, or occasionally veneered soft-wood.

They were often ornamented with fine-carved scroll-work and columns.

The common double-needle apparatus was around twenty-four inches tall

by fifteen inches wide, with a six inch square box for the alarm on

top. The earliest single-needle instruments of Highton were similarly

substantially housed, in pointed-arched cabinet-quality cases about

twenty-four inches tall and nine inches broad. Dial faces were often

silvered and lacquered, later coloured enamels were used to contrast

with the blued metal needles. The needles were later enamelled in

white. Within the instrument the workings occupied a small space

unrelated to the cabinet size, especially after the alarms were removed

in the 1850s. The outward size and material quality was intended to

represent the importance and value of their function.

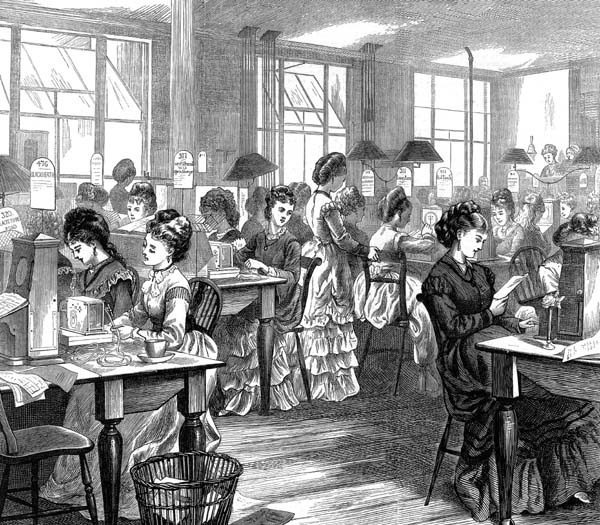

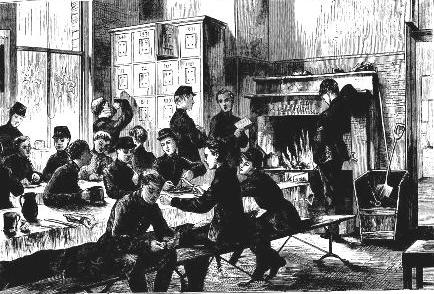

The Telegraph Office at the International Exhibition, Dublin 1862

Almost the only accurate view of local public telegraph facilities

in the 1850s and 1860s

The degree of public service was variable; for instance, even in quite small towns the company's telegraph offices were open twelve hours a day, from 8am to 8pm, six-days-a-week, but the offices at rural railway stations, not all of which on the line had telegraphs, were open, along with the ticketing offices, only at the times when trains were due. The bulk of public telegraphic traffic, estimated in 1867 as between three-quarters and four-fifths of all business, was communicated between the hours of 10am and 4pm between twenty offices in the largest cities.

The following forty-nine cities and towns in Great Britain had a twenty-four hour a day telegraph service in 1860, by either the Electric or Magnetic companies' circuits: Beattock, Belfast, Bilton Junction, Birmingham, Bristol, Broxbourne, Cambridge, Carstairs, Chester, Coatbridge, Coventry, Crewe, Cromer, Darlington, Derby, Doncaster, Dover, Dublin, Ely, Glasgow, Greenhill, Kingston (Surrey), Lancaster, Liverpool, London, Manchester, Milford Junction, Motherwell, Newcastle-upon-Tyne, Normanton, Northallerton, Norwich, Peterborough, Preston, Rugby, Selby, Southampton, Stafford, Stirling, Stratford (Essex), Thirsk, Tweedmouth, Warrington, Watford, Wolverhampton, Wolverton, Worcester and York.

By the late 1860s there were around 220 minor railway stations where the telegraph company did not maintain a separate office but the "station master might send and receive messages to oblige residents". There were in addition 350 other "auxiliary stations" where railway staff could accept messages for forwarding for an additional fee, which they kept as a gratuity.

In many towns, where the telegraph was distant, hotels and other public establishments served as "Official Agents" of the telegraph company, to transact its business. These would forward by messenger any message received to the nearest office, usually at a railway station, at extra cost.

During the mid-1850s the many railway news-stands and bookstalls of

W H Smith & Sons accepted the message forms of the Electric

Telegraph Company, passing them on to the instruments at the railway

stations that they served. W H Smith was a director of the Company.

It was not until the 1860s that the majority of telegraph offices were open on Sundays, and then only for limited hours in the morning and late afternoon. Where the service was available there was a 1s 0d additional charge for Sunday messages.

The general public only gradually frequented the telegraph; in

Liverpool in early 1854 of 4,993 messages examined, rather

impertinently, by the Magnetic company only 201 or 4% were personal or

domestic in nature, the balance were all sent on business, although 233

did relate to betting, which might or might not be personal. When the

exercise was repeated by the Magnetic thirteen years later in February

1867, with an analysis of 1,000 messages through Liverpool, 124 or 12½%

were defined as personal, and just one involved betting – indicating at

least a moral improvement? Again the balance was related to commerce.

Another survey, of a thousand messages, by the Magnetic in 1853 showed that the speed of a message from the sending counter in its stations to the receiving counter averaged from 4½ to 5 minutes.

On January 1, 1858, ‘The Telegraph

Guide’, intending to be a monthly publication, was announced, being a complete

guide to every telegraph station in the United Kingdom, with hours of

attendance and charges from London, Liverpool, Manchester, Dublin, Glasgow and

Hull to every other telegraph station in the country. With a price of 1d, a

circulation of 10,000 a month was promised by its publishers Lee and

Nightingale in Liverpool. Surprisingly, given the complexity of the national

network in that year, it was not a success.

The dependence on the commercial and professional classes for revenue is best demonstrated by the proximities of the telegraph offices in London. As well as their Stock Exchange and Royal Exchange branches, the several companies' closely-adjacent stations in Lothbury, Threadneedle Street, Old Broad Street and Cornhill were next to the banking, financial, mercantile and shipping firms in the City. Those in Mincing Lane and Mark Lane in the east of the City were for the produce and commodity markets. The legal profession, and latterly the press, were served by the telegraphs in Holborn, Chancery Lane, Strand and Fleet Street. Only the common offices in Charing Cross and Cockspur Street could be said to serve a purely 'public' market.

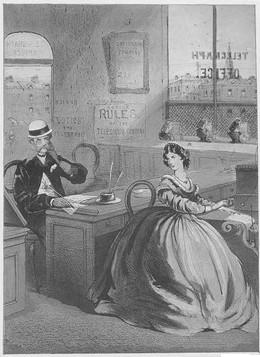

The Telegraph Office at Nine Elms 1844

Two-Needle and Dial Telegraphs at work during an electric chess match

The telegraph office front counters were all partitioned off into

spaces “from two feet to two feet three inches in width” where there

were pre-printed message- forms

on which the sender had to write their communication, along with the

customary institutional ink-wells, pens-on-chains and pencils. The

counter clerk wrote-in the charges to pay and a unique message number.

On the reverse the form listed the contractual obligations of the

Company; the form had to be signed by the sender in agreeing to these.

The larger offices

"had counters at a height suitable for writing, when standing, and

sub-divided into spaces, with fluted glass screens between each, to

prevent any person seeing another's message".

In return for the message forwarding form the clerk provided a numbered Receipt to the sender detailing the recipient, the destination station and the charges paid or payable on delivery. Pre-payment was generally insisted upon for all public messages, but regular customers were permitted a daily account which had to be settled in cash each evening.

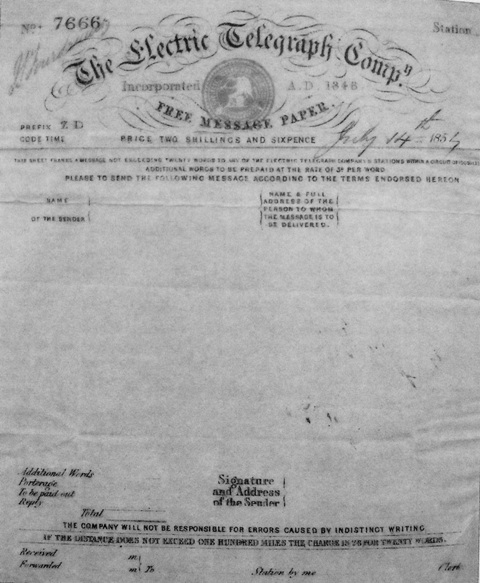

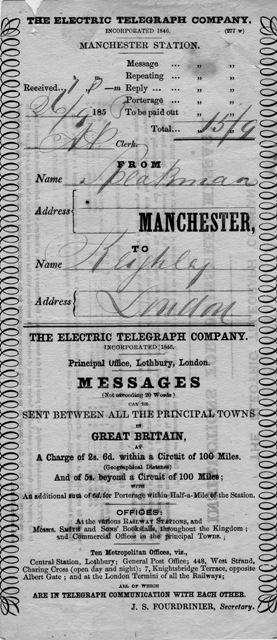

Message Receipt Form 1868

Issued at the stations of the Electric & International Telegraph Company

on sending a message. On the back is a list of the stations in London

and some of the most important towns

For people who could not write the clerk would fill-in the message form and read it back to the sender, ensuring after that they made their "mark" of recognition.

All of the telegraph companies in Britain accepted messages in foreign languages, but at the sender's risk.

The message number was entered on to a list and the form passed to the instrument. Once the message had been sent the form was returned to the counter clerk who crossed it off the list and set it aside for filing. If, by reference to the list, the message had not been sent and returned within fifteen minutes it was chased-up.

Originally no one was allowed free messages; the directors and shareholders of the telegraph companies paid the same message rate as the public.

There were two other printed forms used by the office clerks: the Message delivery form, used for received messages, and the Message transmission form, used within the larger offices for transcribing or copying messages from one circuit to another. Each sort of form was printed on different coloured paper.

Where porterage or delivery to a

distant address was estimated and paid in advance any 'overplus' was

repaid with a money order drawn

up by the secretary, cashable at any of the Company's offices. These

orders proved a fruitful source of petty theft by the less responsible

among the "boy" clerks.

Odd stationery included Advice Notes left at addresses by messengers to show a message had to be collected; an Indemnification Note to be signed by the sender if a message might render the Company liable to action; a Number Sheet that the instrument clerk had to fill-in each day logging his work; and a Transmission Note where a message had to be transcribed to another company's circuits. There was also a pre-printed Funds & Share List that just had to have the numbers added next to the appropriate stock title.

The companies distributed a Card of Rates from most large towns as part of their publicity.

Issued to message senders by the London & Provincial Telegraph Company,

the new name for the London District Telegraph Company.

There was an advertisement on the reverse.

The telegraph companies were periodically criticised in the press for errors and delays in transmission of messages. However in the mid 1850s only one in 2,400 messages on the Magnetic company's circuits was found to contain error, and two-thirds of these were due to the "indistinct writing" of the sender. Even the oft-vilified London District Telegraph Company insisted that only one in 2,000 of its messages was subject to complaint. The number of messages "lost" in transmission was, over the companies' lifetime, in single figures. Delays of over one hour in sending on national circuits were reported by messenger to the sender with the options of cancellation and a refund or sending when possible.

During 1864, after being criticised in the London news press, the United Kingdom company revealed that it received on average one complaint for every 1,729 messages sent using its American telegraphs.

However in 1853 a telegraph clerk in London incontinently added an

extra zero to a merchant's order for £8,000 sent from Manchester.

Fortunately it was questioned by the merchant's agent at the Founders'

Court station and the error immediately discovered without reference to

his distant principal as it had been recorded on the tape of a Bain

printer.

On October 7, 1846 one of the grimmer aspects of electric

communication was brought home on the circuits of the South Eastern

Railway. A man named Hutching, who had poisoned his wife, was to be

hanged at Maidstone gaol at 12 o'clock on that day. The Home Secretary

on receiving a representative of the condemned telegraphed Maidstone

with a stay of execution of two hours whilst his officials investigated

the appeal. The new evidence proved inadequate and the Home Secretary

sent another message by telegraph instructing that the execution should

proceed immediately. The clerk at London Bridge station refused to send

the message for the execution without additional authority; his refusal

was endorsed by the railway company's chairman, James McGregor. A

messenger had to be sent to the Home Office in McGregor's name to

obtain the personal written instruction of the Home Secretary. It was

received and Hutching was hanged that afternoon.

Electric Telegraph Company - Station Staffing 1860

........................Male...........Female

.......Messengers

Liverpool............21...............25................23

Manchester........28...............21.................19

Glasgow..............15.................-...................8

Edinburgh..........12.................-...................8

Birmingham.......16.................-...................8

Hull.....................9..................-..................4

Leeds...................8..................-..................6

Aberdeen............4...................-..................2

Bristol................16..................-..................6

Nottingham.........3...................-..................2

Stock Exchange...6...................-..................2

Southampton......9.................. -.................11

Central Station....6..................107.............93

The Correspondence Department, the largest in the Company, managing the message traffic, consisted of District Superintendents, Cashiers, Chief Clerks, Counter Clerks, Instrument Clerks and Messengers. In minor stations the role of chief clerk, cashier and counter clerk might be combined.

The Counter Clerk, probably the most important individual in the Company's structure, received messages, computed charges, received payments, enclosed messages in envelopes and despatched them by messenger. Except in the largest offices where there were Instrument Clerks dedicated to working apparatus, the Counter Clerk also sent the messages.

The Cashier was employed in large stations or in District offices to record income and disbursements.

The Chief Clerk, called by the Electric Telegraph Company, the 'Clerk-in-Charge', kept the diary, the complaints-, the mail- and the general order books. As the station manager he was also responsible for the Messages Forwarded Book, the Messages Received Book, the Porterage Book, the Postage Book, the Gratuities Book, the Petty Cash Book, and the Pay Bill. Each month there was a Balance Sheet to compile and summaries of the office books, as well as a Weekly Instrument Report and a Weekly Signal Report on the state of the circuits, and Monthly Returns comparing the last three months and the year-on-year figures for head office. For offices at railway stations there were also Railway Message and Railway Signal Books to maintain. Messages there were carefully divided into Commercial and Railway.

One of the more arcane functions within the telegraph office was that known as translating. This involved the rewriting of the sender's message into an abbreviated telegraphic script before being passed to the instrument; and the reverse function at the receiving end. The companies in Britain reduced each of its station addresses to two-letter codes; in addition letters, syllables and portions of words were excised, with conventionalised instrument signs introduced for full-points, paragraphs and underlining to shorten the message.

Common words such as 'the', 'from',

'and', 'to', 'you', 'yes' and so forth, and terminations such as

'-tion', '-ing', and '-ment', were reduced to signs.

As a cautionary note, the word "translating" was used in telegraphy at the time to represent several other functions including forms of electrical relay.

Early CodesFrancis Whishaw, who managed the message department from 1845 to 1848, devised a translating system for business traffic sent by the Company similar in principle to short-hand. Codes were prepared for shipping, horse racing, share lists, corn-market prices, and so on. The sending clerk signalled the code being used and the common phrases and words for that special traffic were substituted by arbitraries, as in short-hand. This translating system reduced message length on a ratio of five to three, five hours work might be done in three.

Frederick Ebenezer Baines, a former telegraph clerk, gave a description in 1895 of the earliest codes used by the Electric Telegraph Company:

“The ‘codes’ were not those used by the public for the sake of shrouding the meaning or lowering the cost of telegrams, but Whishaw’s Codes of 1846, which substituted a brace of letters for names of men or places or a group of words.”

“They were ingenious devices, but of little practical utility. Out of these, however, came IK, the code equivalent of the name of the chief station (Lothbury).”

“The double-needle apparatus of Cooke and Wheatstone was in use. The needles at first were long and heavy. They waved to and fro across the face of the dial with exasperating slowness. About six or eight words a minute was a fair working speed, so the saving or abbreviating of words was of real importance. In later years, with shorter and lighter needles, as many as 40 words a minute could be read with ease, then codes were of still less value.”

“Mr Whishaw’s codes, however, furnished a good deal of information by the use of four letters - two for principles and two for details. Thus, ZD or ZL meant a number of some sort; AM a particular number - one for instance. ZY meant a telegram of some sort, CW a private one. So in this rather cumbrous way the first paid private telegram of the day was signalled: ZD, AM; ZY, CW. [i.e. Number One; Message or Telegram, Private] A telegram in the earliest days of all was delivered to a merchant in Sheffield with these cabalistic signs upon it, much to his bewilderment.”

“CW existed until recently [1895]; amongst the old stagers it is still understood, but M has freely taken its place. ‘What caused the delay?’ would ask an official querist. ‘A very long CW to Birmingham,’ might be the answer forty years ago; or as now, ‘Derby had a good many M’s on hand.’ ”

“ZM referred to wind and weather. ‘ZM fine,’ is still a frequent entry in the office diaries, London fogs notwithstanding. DO for shipping news, and CS for Parliamentary intelligence, survived until the transfer of the telegraphs to the Post Office. Then the work of editing news was handed over to the news agencies, and many of the old codes fell into disuse. CQ, meaning all stations, still holds its own.”

“PQ was one of the last to go, as it was, in the order of signals, the last for use in a message. It was an innocent code enough, meaning only ‘end of message.’ But under certain circumstances it could goad the distant operator to fury; because, abruptly given, it might have the significance of ‘Shut up!’ ‘You’re a muff!’ and other interjections more vigorous than polite. Now, for the clerk, say at York, to be PQ’d by IK [Lothbury] in the middle of some courteous explanation of the causes of slow reading 200 miles away, was more than the best-balanced mind and strongest apparatus could stand; and it was a common occurrence for the stout brass handles of the double-needle telegraph to be broken off by the aggrieved clerk in the white heat of his passionate telegraphic remonstrance.”

“Beside IK for London, Whishaw’s Codes provided IH for Liverpool, AP for Manchester, GX for Hull, KM for Newcastle; EL for Edinburgh, FO for Glasgow, and so on. The initials did not necessarily bear any relation to the names of the places, and ultimately the codes were rearranged in order to produce some sort of connection between the two. The LY stood for Lothbury, instead of IK; and MR for Manchester, BM for Birmingham, GW for Glasgow, etc., replaced the arbitrary codes formerly used.”

Baines imagined an early conversation using the Whishaw Code:

‘Are you through to KU [Normanton]?’ might have inquired the genial manager, Mr W H Hatcher, circa 1850, of Mr [John J] Jackson, the superintendent [at Lothbury].

‘Not yet, sir; there’s a want of continuity on the stop E, and full earth on the HN’ (i.e., the left-hand wire to Normanton is broken, and the right-hand wire touches the earth).

‘What are you doing with the CW’s?’

‘Sending them to MI (Rugby) to go on by train.’

‘What is wrong? How is the ZM [weather]?’

‘High wind and heavy rain in Derbyshire. I think the linemen are shifting a pole.’

Diarial entry: ‘11.30, line right. KU reading well.’

Then an unofficial conversation by telegraph between Normanton [KU] and Lothbury in London [IK] -

‘How many CW’s at IK?’ asks KU, about 180 miles away.

‘Twenty-three,’ replies IK.

‘All right; will clear you out.’

Joy overspreads at IK the face of J M, aged fifteen. He signals ‘ZL’ (all being messages for stations beyond Normanton, otherwise he would have sent ZD), and away fly the CW’s, the double-needle rattling like the stones of Cheapside under the wheels of Mrs Gilpin’s chaise*. All twenty-three messages are taken without a single ‘Not Understand.’

‘Good! good! good! [GD, GD, GD]’ signals IK, in a paroxysm of praise.

(* from ‘The Entertaining and Facetious History of John Gilpin’ by William Cowper, 1783)

Other arbitrary early call signs used by

the Electric Telegraph Company for busy offices included KX for the Stock Exchange,

KR for Cardiff, RW for Derby, KT for Stockport and VT for Coventry.

Eventually, as Baines noted, by the

1860s, the major cities and offices adopted, officially or otherwise, more obvious

calls: Liverpool LV, Newcastle-upon-Tyne NC, Edinburgh EH, Dublin DB, Belfast

BT, for example. The other telegraph companies had different call signs for

their offices, the Magnetic used LN for Threadneedle Street, the United Kingdom

company GH for Gresham House, and the District CO for Cannon Street, all in

London. The Magnetic’s calls were commonly distinguished by being three letters

long.

As well as being used in transmission the

calls were incorporated into the india-rubber obliterating stamps used on

accepted message forms and frank stamps at the offices.

"I hope you will join the crusade against the use of the new word 'telegram'. It comes to us from the Foreign Office, I believe. Certainly, no Englishman at all aware of the mode in which English words are derived from the Greek language could have invented such a word. If it should be adopted, half our language will have to be changed."

"We shall have to say paragram instead of paragraph, hologram instead of holograph, photogram instead of photograph, autogram instead of autograph, geogrammy instead of geography, lexicogrammy instead of lexicography, astrogrammy instead of astrography, lexicogrammer instead of lexicographer, polygrammy instead of polygraphy, stenogrammy instead of stenography, stereogrammy instead of stereography, horogrammy instead of horography, ichthyogrammy instead of ichthyography, micogrammy instead of micography, metallogrammy instead of metallography, &c. In short, we shall have to retrace our steps, and entirely alter our manner of forming English words from the Greek. Have all our lexicographers been wrong? And is the author of 'telegram' the only person who is right?"

Special signs were also used unofficially between the clerk-operators by 1848 to represent emotions such as laughing and astonishment. The adaptability of human nature to this the most revolutionary of technology was remarked on at the time.

The Electric's C F Varley noted in 1859 that "telegraph working generally causes great nervous irritation, and the clerks are very prone to quarrel". He cited delays caused by impatience with repeated errors by distant colleagues leading to electrical arguments, and to clerks refusing to work with those on some lines.

Every message had a Prefix consisting of two or three letter codes.

The first was the Message Type: free, special express, government,

chairman's, duplicate, ordinary, danger, transmit on, engineer's,

urgent, insured, repeated, train report, company and private. This was

followed by two letter Station Codes, the "calls", LY for Lothbury, EN

for Euston Square, WV for Wolverton, RY for Rugby, YK for York, for

example, to identify the originating office and the destination, and a

two or three letter Time Code.

After the message was an Affix, also in the form of short letter codes usually dealing with delivery: acknowledgement paid for, answer not paid for, forward by boat, forward by cab, forward by best means, forward by omnibus, forward by train or another telegraph, to be called for, completion of address, forward by first train, forward by cab or messenger up to three miles, instructions to follow, porterage not paid for, forward by most rapid conveyance without regard to cost, forward by special express,forward by post, reply paid.

There were arbitrary responses signalling Engaged, Engaged to all business and Now Un-engaged; for Repeat all, Repeat from, Repeat word after, Repeat word before, Repeat words from/to, Word Number incorrect, Wait, which indicated an error in transmission, and All Right, when the error was corrected. There was a "collate" signal inserted into messages that indicated the next word was to be repeated back to ensure accuracy. There was also the End signal at the termination of the message, and the all-purpose Good signal (GD) which was the British equivalent of OK.

Interruption of messages was forbidden; the reason for the signalling of the Wait code from the receiving station had to be documented.

In the early days of the Magnetic company each word had to be

confirmed as it was received by the instrument clerk to ensure

accuracy.

Business customers were allowed use of commercial Telegraphic Vocabularies

that substituted words and numbers for most common phrases. These were

published with the object of shortening messages for economic reasons

rather than to conceal the content. The Magnetic company estimated that

one message out of four was encoded in 1853.

However, stockbrokers, produce-brokers, merchants, banks and betting-men used codes and ciphers, commonly called a Private Key, for their confidential messages from the earliest days. The words in their Private Key, or code book, could not exceed two syllables to prevent abuse of the tariff and confusion in sending. Banks also used an authorising code phrase that preceded the text of their business messages. The phrase changed each day. Such messages related to delicate subjects such as the returning of bills-of-exchange and the stopping of local bank notes. Remittances between banks of £20,000 and £30,000 were regularly authorised this way by telegraph in the 1850s. The banks also "enquired as to the respectability of parties" by wire in that period, keeping the "party" waiting in the bank parlour until the reply was received.

Receiving bulk traffic, news messages, for example, required two

clerks; one to read the instrument, the other to write down the script

in a manifold book of alternate flimsy sheets and carbon-paper. The

original was delivered to the recipient, the facsimile kept for the

record. The sending of such messages required considerable

concentration, flicking attention from script to instrument, sending

letter-by-letter without translation. It was this traffic that, in the

earliest days, the Bain and American writers were intended to mechanise

and render more accurate especially on long and busy circuits. News

messages having special importance or priority were sent Express or in industry vernacular as Expresses.

Apart from government traffic, which the Companies were obliged in law

to give preference, 'Expresses' of news were then the only priority

paid messages.

Whether sending or receiving, the unique number and the hour and minute of commencement and completion of each message were recorded, and signed-off by the clerk. All of this detail and the message content was entered into the books of the Company, along with the charges paid, for accounting purposes and in case of any dispute with the sender or recipient.

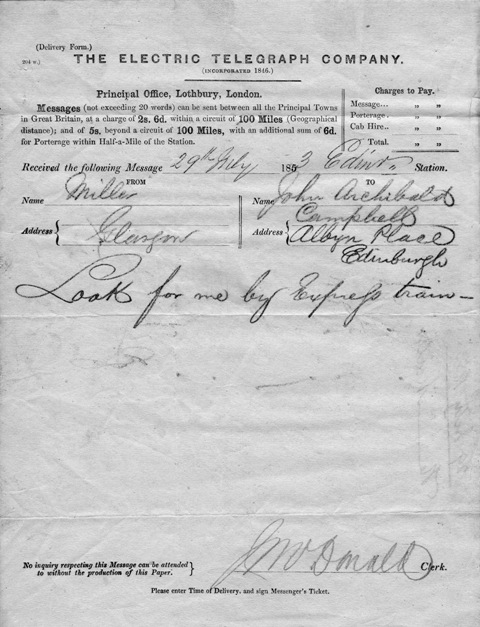

Electric Telegraph Company Delivery Form 1853

What came to be called a "telegram", hand-written by the clerk

in pencil on a "manifold writer" to make a duplicate copy

As

well as news all other messages were written out by the receiving clerk

on a "manifold writer" (i.e. copying by carbon paper) and a duplicate

copy of every message sent by telegraph was forwarded by rail to the

Central Station at Lothbury to be compared with a copy of the original;

through this process it was said that the clerks had to be particularly

accurate, and the public efficiently protected from error. The copies

were parcelled-up, placed in hampers and kept under lock-and-key for

two years before being pulped.

At the Central Station where the business was intense there was a division of the clerical work into three areas which would otherwise have been done by one or two individuals: 1] two clerks to each instrument, one to read or send the signal, one to write down the received messages; 2] registering, numbering and making an abstract of each message; and 3] pricing, folding, sealing and addressing the message.

From the earliest systematic use of telegraphy in Britain the clerk-operators could recognise the telegraphic hand of their regular sending colleagues hundreds of miles distant, and engaged with them in private, unofficial electrical banter, to management's disapproval.

A Messenger of the Electric Telegraph Company

The

frock coat was in dark-blue with a scarlet collar and scarlet

cuff piping,

the trousers were grey. The cap was dark-blue with a

broad scarlet band, originally a flat-topped military pattern, later in

the French-style shown.

ETC monogram on cap, collars and pouch.

The other principal category of employee in the office was the uniformed messenger, a young boy, who carried the received message forms to addresses within one mile of their office in, as the Company stated reassuringly, carefully-sealed envelopes. For messages received on the Hughes type-printing telegraph the printed tape was cut into short lengths and glued to the ordinary received message form, for the convenience of business people who filed them as letters, before being folded-up and inserted into the envelope; only the outer address was hand-written. In the United States the printed tape was simply put in the envelope.

In Britain and the United States messages were always sent out in envelopes. In most other countries the message sheet was folded several times, the address written on the outside of the message form and one edge sealed with a small adhesive telegraph label.

The small white envelopes of the Electric Telegraph Company carried their crest and the exciting (or terrifying) injunction “Immediate” printed in red on their face. Those of the Magnetic company were overprinted blue with its crest. The District company had demur plain brown envelopes simply marked “Telegram”.Each messenger carried a book of numbered Receipts that recorded the message's number, sending and delivery times and any charges to pay on delivery. The messenger had to obtain the recipient's signature on the receipt. No tips were permitted.

Where no messengers were employed, in the smallest offices, the

message was passed to a self-employed porter or a railway porter at the

sender's risk, or put into the Post Office mails for delivery.

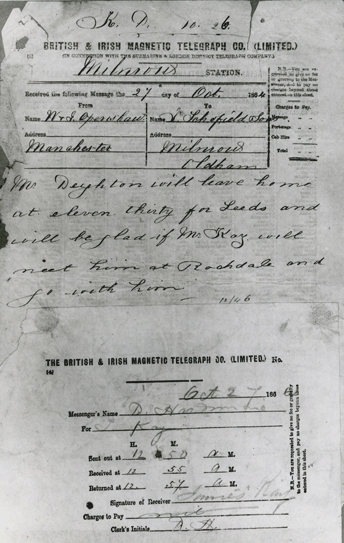

British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company Delivery Form 1864

along with the Messenger's receipt

There was a list of telegraph stations and foreign rates on the reverse

The Electric Telegraph Company issued a number of

manuals for the guidance of its staff: the principal of these were the

General Regulations.

Originally in 1850 these were in two parts, for clerks in stations and

for inspectors and linemen. But these were eventually combined into a

single 72 page volume. There were also Tariff Books,

especially for continental traffic – which ran from 37 pages in 1859 to

89 pages in 1866 as the foreign connections developed. Instrument

galleries used the 12 page General Code Book listing the

two-letter arbitrary substitutes for words and syllables. The Company

printed one-sheet Double-Needle and Single Needle Alphabets for

training.

At its busy Founders' Court and Charing Cross offices in London the Electric Telegraph Company, as a charitable gesture, allowed red-coated boys from the Saffron Hill Ragged School's "Shoeblack Brigade" to earn an income carrying messages and packages for patrons.

The common telegraph office in a medium-sized provincial town employed only two or three people, the clerks mainly young men, usually called 'boys' or young women, always termed 'ladies', and the messengers, working long 'shop' hours, six-days-a-week, in small, often shared premises.

Clerks and messengers worked either nine hour days

or eight hours during the evenings and nights. Only older, male clerks

were permitted to work at night.

The instruments and apparatus used in telegraph offices were limited in number. The assembly included:

• Telegraph – the sending and receiving instrument, commonly a single-needle instrument in circuit with the line and the battery

• Galvanometer – a small desk-top instrument for measuring the current in the line circuit; a portable galvanometer used to test battery and external circuits was called a Detector

• Bell or Alarm – in the line circuit to call the attention of the clerk to activity on a message circuit

• Relay – used in the message circuit to automatically forward messages and to maintain any loss of current by using its own battery

• Turnplates – small rotating switches used to direct circuits between instruments and between batteries and apparatus, also termed Commutators

• Switchboard – used in large offices to manage message or battery circuits instead of turnplates

• Battery – a set of chemical cells that produced the current, usually in a secure place as they contained volatile chemicals, the battery circuit ran to the telegraph instrument and to the relay

• Lightning Protector or Paratonnerre – a device in all offices inserted in message circuits between the line and the instruments

• Screw Connectors – small brass devices used to join circuit wires together

Circuits

In the simplest terms the original electrical circuits for

telegraph comprised a main and return; these were both wires until the

earth return was introduced. Other than for two-needle instruments each

circuit was then essentially a single wire.

The several telegraph stations were all, at first, connected to the same circuit. Each sending and receiving instrument had an alarm attached so that once current was applied the bell rang on all those in circuit to attract the clerks. The alarm was originally continuous and then just a series of single beats. The sending clerk would signal a short two-letter "call" message with the intended station's identification code; the clerk at the appropriate station would then acknowledge the call and take the incoming message whilst the others ignored it. The sending clerk had to repeat the call announcement until it was acknowledged.

All of the stations in the circuit could read the through traffic to other destinations.

With the coming of more intense traffic the ringing of all the bells on the circuit was an unnecessary nuisance as the ticking of the needle became sufficient and the alarm became an accessory only in branch stations. With traffic over great distances or to branch lines where there was no continuous circuit the 'call' signal would be received at a large office, acknowledged, and diverted through to another line using either simple switches or a switchboard to create a circuit. Once this was connected the 'call' signal would need to be repeated again until it was acknowledged. The message could then, after a delay, be sent.

Where no switching for a through circuit was possible the message

was transcribed, re-written, at the intermediate station and re-sent at

a later time (if pressure of work was the cause) or taken to another

instrument on the correct circuit, if no direct connection existed. The

traffic between the busiest stations soon required separate or

dedicated circuits, either a direct, point-to-point, line, or one with

only a limited number of intermediate stations in parallel with the

existing ones. The planning and constructing of these separate circuits

was a critical issue in the telegraphic business.

By 1852 the ordinary lines were divided into Divisions of between four to six stations, between two larger offices, between London and Birmingham for example. These could then only have direct internal access. The messages in or out of the Division had to be switched or transcribed at the larger offices.

One of the duties peculiar to British telegraphy was that related to the need to regularly re-magnetise the receiving needles of the instrument, which gradually lost power over time. Instrument clerks each possessed a permanent magnet for this purpose.

Electric Telegraph Company - District Staff 1860

..................Inspectors – Mechanics – Linemen – Labourers

North..................7............1..................20...............60

South West..........2............1.................10................10

London

...............4............4.................6...................-

Midland...............3............1.................7..................50

Western...............7............1.................29................140

Scottish...............5.............1................16.................?

Great Eastern.......4.............-................11.................40

North Western....10...........3................30.................58

Irish.....................3............1................16.................7

In addition there were 18 crew members on the cable ship Monarch and 108 workers in the Company's stores

An Evening with the Telegraph

This long descriptive piece was published

in Chambers’ Edinburgh Journal, on January 4, 1851:

“The spider's touch, how exquisitely

fine,

Feels at each thread, and lives along the line.”

On arriving at the ------------ station,

I found that my luggage, which was to have been sent on from town, had not

arrived. There was no time to be lost, and on applying to the superintendent of

the station, an order was given to make inquiries at London by means of the

telegraph. Impatient to get some information about the missing baggage, I

strolled to the electric telegraph office, to hear what was the answer

received. But no satisfactory information had as yet been obtained; on the contrary,

nothing at all was known about the matter. I wanted another message sent up to

town, but on working the needles, it was found that the telegraph was engaged

in corresponding with some intermediate or branch station.

The clerk, with whom I continued chatting

through the little opening where all communications are given and received, was

very young; but there was something in his manner that prepossessed you

favourably, and, moreover, there was a total absence of that abruptness of

speech and quickness of manner that seem to have become a second nature with

our railway officials. At last he invited me to enter his office - the very

thing I had been manoeuvring for and longing to do - for as I squeezed my head

through the small opening, and looked into the snug room, warmly carpeted, and,

although it was the beginning of August, with a fire burning in the grate, I

could just catch a glimpse of the small mahogany stand and dial of the

telegraph, with which he had been talking to the people in London about my

trunks, and was very desirous of seeing a little more. Books were lying about

the table, which seemed to indicate a taste not only for literature, but for

its more imaginative productions; and so, then, as we sat over the cheerful

fire, our conversation taking its tone from the volume into which I had dipped,

we chatted about authors, style, and such matters.

“You would hardly believe,” he said, “how

such an employment as mine teaches one curtness: how one gets into the habit of

saying what one has to say in as few words as possible, and yet with perfect

clearness. I write occasionally little articles, and I find that in them I

unconsciously avoid all redundancy of words, just as when transmitting a

message. You have no idea what a lengthy affair the messages are which we have

given us to transmit, with so many useless expressions that make the inquiry,

or whatever it may be, nearly twice as long as necessary. In delivering it, we

cut it down about one-half, and yet our version tells all that is to be said

quite as intelligibly as the original.”

“The cause, no doubt, is, that those who

want to give some information about a missing thing are anxious to describe it with

all exactness, in order to make as sure as possible of its being recognised.”

“But the details on such occasions,” he answered,

“are really without end. Now we, for our parts, seize on the salient features:

we give the necessary marks or tokens, and these only. For nothing is the

telegraph so often put in requisition as to inquire about ladies’ dogs that are

missing. Hardly a day passes without such inquiries. And such descriptions! A

perfect history of the animals’ habits and virtues: it seems they never can say

enough. I have often thought how they would be shocked did they but see how all

the long history of their favourites is condensed into a couple of lines. And

yet it answers the purpose as well.”

He here turned round to the dial-plate of

the telegraph, and after a moment's watching, looked again into the volume, the

leaves of which he was turning over.

“Was any one speaking to you ?” I asked.

“Not to me; they are talking with the ------------

station.”

“But how did you know it ? - what made

you look up?” I asked.

“Because I heard the wires.”

“That's very strange,” I observed: “my

hearing is unusually fine, yet I heard nothing.”

“'It is habit; besides, perhaps, you

heard the vibration too without knowing what it was. My ears are alive to the

sound, that, as I sit here reading, the instant the hands of the dial move, I

hear them. That low click-click attracts my attention as surely as the bell.”

“There is an alarum, is there not, which

sounds when the clerk's attention is required?”

“Yes,” he said; “this is it.” And so

saying, he touched a wire, and instantly a hammer struck upon a bell, making a

slow, penetrating, long-continued noise. “But I generally stop the communication

with it, for it is so loud, that it is extremely disagreeable to be disturbed

by the ringing of that thing at one’s shoulder. Besides, I hear the other just

as well, let me be never so immersed in what I am about.”

I now heard such a snap as takes place

when, on putting your knuckles to an electric machine, the spark is produced.

It was repeated, and on looking up, I saw the needles reeling to and fro. The

clerk observed them for a moment, and then rising, went to the machine. Backwards

and forwards they went, to the right and to the left, then with a jerk half-way

back again - left, right, left - left, left - jerk, jerk - right, left, jerk,

and so on; while the clerk, who held two handles hanging from the instrument in

his hands, every now and then would also give a good rattle with them, and pull

them right and left, and give an answering jerk. All the time, of course, he

was looking fixedly at the dial-plate, as he would have done into the

countenance of a person who was speaking to him, and whose character he fain

would learn from his looks. Jerk, jerk, jerk - rattle, rattle, rattle - all was

done; and writing down the message on a slate beside him, he copied it

afterwards on a paper to give to one of the porters. It was about some boxes

sent on to ------------ by the last train.

“I know what clerk sent down that

message,” he said. “It was ------------ .”

“But how do you know which clerk it was ?”

“By the manner of his handling the

needles, and their corresponding movements. I am as sure who is working them as

if I saw the person with my eyes. You of course would not detect any difference

in the vibrations, yet there is a very great difference. There may be timidity,

indecision, flurry, or firmness, in their movements. You see quite clearly if

the person speaking to you is master of what he is about; if he does it with

ease and decision, or if he is spelling his way, and anxious about getting

through the matter well. And it is not only the quickness of the delivery that

shows whether the person is skilful or not, but his very character communicates

itself to the wires, and shows itself in the movements of the needles.”

“How strange! - and it is really

possible?”

“That in a man’s movements much of his

character is shown, you will allow. Well, as he takes hold of the handles to

work the telegraph, he does it in a way corresponding with his own particular

individuality. That is communicated to the wires, and here on the dial-plate I

see the inner man before me. The person I just mentioned is a very good fellow, but

cautious, undecided - never sure whether what he does will be quite right or

not. He is always hesitating; as soon as his hand touches the instrument, I

know it is he instantly. There go the needles slowly from one side to the

other, as if not quite certain about going across or not; they never go back

suddenly, but always take their time, and move right or left hesitatingly, and

with no decided swing. It is as like the man who is moving them as it is

possible to be. It is quite a reflex of his mind: there is the impress of him exactly

as he is. And it is very natural it should be so. The least hesitation or doubt

communicates itself involuntarily to the hands as you hold the handles working

the telegraph; and so fine and sympathetic is the conducting power - so

sensitive are the wires- that every passing shade of feeling is felt by them.

On the dial-plate it is all betrayed. Just as the mind of him at the other end

of the wire is wavering, exactly so the needles are wavering too. Now he feels

more sure; and yet that very same instant the change that has gone on within

him is marked there also: the needles swing directly with sudden decision.”

“This is really very interesting,” I

said; “and it is besides, to me at least, a new wonder connected with electric

communication. That one should be able to talk with a person a hundred miles

off, as if they were both face to face, is certainly extraordinary; but that

the affections of the mind and their sudden varyings should be instantaneously

transmitted such a distance - perhaps even before the individual himself was

aware of them - this is assuredly very much more wonderful!”

“'It is not,” he continued, “in the

manner of delivering a communication only that you discover the sort of person

with whom you have to do. The way in which he receives yours is also very

indicative. One, slow of thought, will let you give the whole word; while another,

of quick comprehension, and of a bolder nature, will give the sign, ‘I understand,-

at the first letters. The very jerk too, which signifies that you know what is meant, is given by one with a decided,

sure, firm knock; while with another, of a hesitating character, the needles

seem to be hesitating too!'

“Just now,” said I, “while you were

receiving a message, I observed that every now and then you gave an unusually

strong jerk - much stronger than the others. What did that mean?”

“Oh,” said he, laughing, “that was an

indignant ‘Understand!’ The other was stopping to see if I knew well what he

had said, and I showed, by my manner of saying yes, that I was out of patience

with his distrust. Such an ‘Understand,’ given in that brusque manner, is not

exactly very civil: but I really can't help it - one gets at last out of patience

with such dawdling.”

“And will the other, think you,

understand that his questions and slowness put you out of patience?”

“No doubt of that. I knew he understood

the way I answered him, and was sulky about it, for his manner changed

directly. In the way I said ‘I understand,’ was expressed besides, ‘Of course I

understand! Do get on, can’t you, and don't stop to ask such foolish questions!’

That is what we call an indignant “understand!”’

All this interested me much; and we

talked on, now about a favourite author lying on the table, now of this thing,

now of that, only interrupted occasionally by the click-click of the mahogany

case, that, like a something endued with life, was calling its attendant to

come to it, and take heed. But while there, as one in presence of some demoniac

thing, the telegraph exercised a sort of spell over me; and I always recurred

to it, much as our conversation on other matters would have pleased me at any

other time.

“You must not leave the telegraph for a moment?”

I observed. “There must be always some one here to watch it, and be in readiness?”

“'Yes; I or my brother remain here

always. We take it by turns. Night and day he or I am here. He is gone to-day

some miles off; so I have taken his watch for him. I was on duty before;

to-night, therefore, will be the third night I have been up!”

“It must be very fatiguing for you;

besides, you cannot venture to doze a little, lest something should happen.”

“'Though I were to do so, if the wires

began to move, I should awake directly. I cannot tell you how or why it is, but

if there is the slightest tremor, I am sensible of it at once. Whether I hear

it or feel it, I do not exactly know; but I am sensible that they are moving !”

“By intense watchfulness, by constant companionship

with that animate yet lifeless thing, a sort of sympathy, or magnetic influence

- call it what you will - may exist between you and it,” I observed.

“It may be so,” he replied; “but really I

cannot say. The strain of attention that all occupation with the telegraph

produces is very great. While reading off the communications just given, your

mind is on the stretch. The intentness of observation with which you must follow

the needles in their movements is very fatiguing. There is nothing hardly that

demands suck minute attention; for a slight mistake, and you lose the thread of

the meaning, and this directly causes delay. Besides which, you get confused.”

“This constant state of excitement must,

I should think, at last make itself felt. It would be highly interesting to

observe the influence it would exercise. Now, in yourself, have you,” I asked, “remarked

that any change has taken place since you have been occupied with the telegraph

- that you are more irritable and excitable than before - or that the constant

tension in which the faculties are kept has at all affected you ?”

“I think it has made me more excitable

than I was before. It certainly has an effect upon the nerves. Tho vibration of

the needles, for example, I should hear much farther off than you would - so

far, indeed, that you would think it scarcely credible.”

“Besides the constant attention and the

night-watching, I have no doubt that the incessant, quick, uncertain motion of

the needles backwards and forwards, and from side to side - that constant tremulousness

which you are obliged to observe and to follow so closely - must tend to

irritate.”

“Yes,” he replied, “I daresay it is so.

At night, however, one is seldom interrupted. Towards morning the foreign mails

arrive, and then the despatches for the newspapers have to be transmitted. This

takes about a couple of hours or more close, uninterrupted work. When a

correspondence continues thus long without a break, it is very tiring for the

mind. As soon as it is over, all has to be written down in a book: this is the

most uninteresting part of our occupation. Every message, important or not, is

entered in a journal, and then, from time to time (every month, I believe.), the

accounts and money received are sent in, and the journals at the different offices

compared, to see that all is right. All this is tiresome enough, but it must be

done.”

“In this way you hear all the foreign

news before anyone else. When the first morning edition appears, to you it is

already stale. I wonder, though, that persons who have anything secret and important

to transmit, should like to trust their secret to two individuals wholly

unknown to them.”

“Oh, there is no fear of our divulging anything,”

he replied. “Get something out of an electric-telegraph clerk if you can!

Besides, we are forced to the strictest secrecy; bound, too, in a good round

sum of money, which we must deposit as security (If I remember rightly, £500). There

is nothing to be got out of us, I can assure you. It would never do if it were

otherwise; for often matters of very great importance are forwarded in this

way, and the confidence placed in us must be entire, and our secrecy above even

suspicion.'

He afterwards showed me his dwelling.

Close to the office was a sitting-room, and opposite this the kitchen, &c.

Above stairs were the bedrooms; and though all was on a small scale, the

arrangements were as comfortable as one could wish. I observed this to my new

acquaintance, and that all was neat and well planned.

“Yes,” he answered, “it is so. The

company have not been sparing in making us comfortable. All is as nice as we

could desire it to be. It is really very necessary, however, that it should be

so; for, being obliged to be always here ready and on the watch, one could

hardly do without these little comforts. My brother and I are happy enough

together.”

“I should think,” I observed, 'the

employment must have much in it that is pleasant -a charm peculiar to itself?”

“You are right,” he said; “at first it

possessed an indescribable charm. There was something mysterious about it; and

it was with a strange feeling, unlike anything I had ever known, that I used to

find myself holding converse with others far off, and watching, as it were,

their countenances in the dial-plate. But the novelty over, all this died away;

and though I still like the employment, it is no longer invested with its

original charm.”

“Were you long in learning to work?” I inquired.

“Not very long - it is not so difficult;

but it takes a long time before you are able to read the communications sent to

you - that is to say, quickly and easily. The speed with which a message is conveyed

depends much on the person receiving it; for if he is quick and clever, he will

understand what the words are before they are spelled to the end; and so,

meeting the other, as it were, half-way, the communication is carried on with

great rapidity.”

Here the hammer of the alarum, which,

before we went into the other room, had been set, began making a tremendous noise.

“Ha!” said I, “someone is about to speak

with you.”

We went to the door of the little

parlour, and looked into the office at the needles. They were moving backwards

and forwards with their usual click-click.

“Is it for you ?” I asked.

“Yes,” he replied; “so many times to the

right, and so many times to the left, that signifies ------------ station.”

“What is it about?” I inquired, as I

watched the two needles, which, by their different movements over the small

segment of a circle, expressed everything.

“It's about the down-train to-morrow. We

are to send up some carriages.”

“And where is it from ?”

“From the chief station in town.”

The needles soon moved again.

“Is it still the people in London who are

speaking ?”

“'No: now it is the ------------ station”

I now had an opportunity of seeing how

quickly my companion read the movements of the needles. Incessantly came the

jerk, meaning “I understand;” again and again at quickly-repeated intervals.

Once there was an unusual movement, and I afterwards inquired what it meant.

“It meant,” he replied, “‘Say that once

more.’ I could not make out what was said; and, just as I imagined, the other

clerks had made a mistake.”

Now came the answer; and it was

astonishing how quickly it was delivered. As one's words pour out of the mouth

in speaking, so here they were poured forth by hands-full. How the needles

rushed backwards and forwards, then halted! now came a quick shake, and then

off they dashed to the side with a bold decided swing! There was no hesitation

here. Rattle, rattle, rattle; right, left, right: on it went without a pause;

and soon the people at ------------ had got their answer from the snug little

parlour at the ------------ station.

The evening had closed in, and there I still

sat over the fire. A fire - a coal-fire in an English grate has a wonderful

attraction for an Englishman who has been a long time from his old home. This

was the case with myself; and therefore it was, I suppose, that I hung about

the hearth as one does about a spot that is fraught with pleasant recollections.

It was quiet, and cheerful, and cozy. Presently the clicking noise was heard

again.

“Ah, ah! it is from the ------------

station,” said my companion, rising. “It is a friend of mine who is speaking,”

he continued. “He wants to know if I shall come up next Sunday or not. ‘I—don't—think—I

shall,’” he said, repeating the words he was expressing by the wires. “He asks

me if ‘I am alone.’ No—a—friend —is—here—with—me.”

“'I am glad you have somebody with you,

and are not alone, for it is most confoundedly dull,” came back in reply.

“Almost every evening,” said my

companion, “we have a little chat before night comes on. He does not like being

alone, so he talks with me”

“Who have you got with you?” asked the

friend so lonesome at the ------------- station.

“No—one—you—know” was the answer.

“I tell you what,” I said, laughing, “I'll

give him a riddle. Ask him, from me, ‘When did Adam first use a walking-stick ?’”

“When Eve presented him with a little

Cain (cane),” came back as reply almost directly.

“Confound the fellow !” I exclaimed; “I

am sure he knew it before;” and we both laughed heartily.

“'Confound—the—fellow—I'm—sure—he—knew it—before”

- repeated my companion by means of the wires.

“Look at the needles,” I said; “how they

are moving!”

“'Yes, he is laughing,” he replied; “that

means laughing! He is laughing heartily!”

Shake! shake! shake! shake! We laughed

too in return by telegraph, just as we were then doing in reality. Another

hearty laugh came back, with a “Good-night!” We wished “Good-night” in return,

and our bit of chat was over.

And soon after, bidding my friend a good-night too, I left him to pass the long hours till morning in companionship with that wonderful thing, which, though lifeless, was so sensitive, and though inanimate, could yet make itself heard by him who was appointed its watcher; its low yet audible vibrations being as the pulsations of a heart that at intervals, by its faint beating, gives sign of vitality.

Normanton railway station 1845

An isolated location in West Yorkshire where the lines of the North Midland,

Manchester & Leeds and York & North Midland Railways conjoined.

One of the most important transmission or relay stations of

the Electric Telegraph Company, linking the north and the south.

A drawing by Arthur Fitzwilliam Tait, lithographed by Day Co., London

Normanton

Frederick Ebenezer Baines graphically described the workings of one of the most vital but isolated telegraph stations in the Electric Telegraph Company’s system in the early 1850s:

“There were two spots within the telegraphic area which were not the most ardently desired of telegraphists - Normanton in Yorkshire, and Carstairs on the Caledonian line in Scotland. The former included a railway-station and hotel; the latter, in early years at all events, little more than a signal-box.”

“All the clerks were extremely young and very frugally paid. Their ages ranged from sixteen to eighteen; they had a guinea [21 shillings] a week apiece. A few gray-beards who had attained a score of years had perhaps some shillings more, while a Methuselah of five-and-twenty, who was the clerk-in-charge, might even enjoy a weekly stipend of a couple of guineas. The latter post and pay were, however, the prizes of the profession, and not to be reached at a single bound.”

“The work was wonderfully well done considering. These youngsters, especially at Normanton, had nothing else to think of. The office at that station was a grimy room on a bridge built over the yard. Normanton owed its importance to the junction of four trunk lines of three great railway companies. Some of its public glory may have departed since the days when passengers habitually broke their journey there and slept at the station hotel. But in another way Normanton is a vaster place than ever, with a traffic which no figures can measure. Yet the social gaiety of this railway stronghold is even now not very far from what it was in the remote days of KU.”

“Here we [re-]transmitted for the North, for YO, KM, EL, and FO, i.e., for York, Newcastle, Edinburgh and Glasgow, the last being the Ultima Thule. Sometimes in fine, dry weather IK could work to KM; and a dim recollection is preserved of seeing, on one hot August Saturday afternoon, on the dial-plate at Lothbury faint defections from FO.”

“But Normanton was our frontier point. Beyond we might penetrate by chance. It did not, however, pay to work slowly, with weakened signals, into a dim and misty distance, and to stations only known to us by tradition.”

“So Normanton ‘took’ for Hull and Leeds; for York, Newcastle, Edinburgh and Glasgow, and for the town and county of Berwick-upon-Tweed. In those days, as no other towns of importance were known to telegraph clerks, could it be that they did not exist? Where were Greenock, Inverness and Aberdeen, Dundee and the towns in Fife? Where were the Hartlepools, Darlington and Middlesbrough? Bristol we had heard of, because every Saturday at noon a stock-broking message was sent around by Birmingham to go by train from Gloucester to the great town in the West. But Cardiff and South Wales - we knew them not!”

“At Normanton, amongst a galaxy of fine double-needle readers, shone a bright and particular star, FC. He was dark, young, small and slender; self-contained, gentle in his ways, and a most consummate reader. He could read off the double-needle, it was thought, with his eyes shut - even perhaps during a needful nap! Fifty words a minute, as fast as the fastest sender could work, he, with good signals, was supposed to be able to read with ease. But his glory was to read when signals were bad.”

“Imagine two clock faces, each with a single hand, standing side by side, the needle when at rest pointing to 12 o’clock. When in action, the needles shall singly, or both together, beat against ivory pins sent a little way to the right and left respectively - say at 2 minutes past 12 to the right-hand, and 2 minutes to 12 on the left. That was the normal state of things; and them distracting wobbles, numbering at top speed 400 to 500 a minute, i.e., at an average of five letters a word, and two deflections to a letter, sometimes of both needles in parallel deflections, sometimes of one needle reversing between its pins, had to be instantaneously deciphered.”

“To read the vibrations of one needle, even when the deflections were well defined, seems at first sight sufficiently difficult; but how it was that the signs of two needles moving together, or rapidly changing from one to the other, did not bewilder the reading clerk in a mystery. It is still possible for me [in 1893] to read at the rate of twenty words - that is 200 deflections - a minute.”

“When the signals were bad, distractions arose in three ways: 1) One needle would deflect strongly, the other scarcely at all; 2) one or both needles would be in contact; i.e., the messages of other wires would to some extent leak into our wires and impart irrational pulsations, which had nothing to do with, and only confused, the work in hand; and 3) nine-tenths of the current from London would run down the wet posts into the earth, or dissipate into the moist air of the Midland counties, and only a fraction would find its way to Yorkshire and feebly actuate the needles there.”

“Then was FC seen at his best. As photography discovers stars which no telescope can reveal to the human retina, so FC could read where no signal could be seen by ordinary telegraphists. Those are the days of the far away past. The double-needle has long since gone to the tomb of the Capulets, although contacts and full earth, the aurora borealis and earth-currents, still play their merry pranks in the regions of telegraphy.”

Women

As was often mentioned at the time, the telegraph companies were substantial employers of women. From its commencement the Electric company employed women as clerk-operators; competition for these positions was often embarrassingly high. Although paid less than male clerks their working conditions were far more attractive than factory, domestic or other common female employment. The Electric had separate female management, welfare, social and "toilette" facilities for the hundred women that worked in their own instrument galleries at Founders' Court and Telegraph Street, and all contact by male employees was forbidden on penalty of his immediate dismissal. Initially, and for many years - until the 1860s, women were only taken on in London, Liverpool and Manchester, none were employed in its branch stations.

In the Electric's gallery, when not actively employed at the instruments the ladies were allowed to engage in knitting, needlework and books. It was noted that they were primarily the daughters of tradesmen, with some from the families of government clerks and clergymen. There were strict age limits on their employment; they were only taken on between 16 to 23 years. It was assumed that women clerks would "retire" from their position upon marriage.

The Electric company provided their female, but not their male,

clerks with tea, coffee, bread and butter, every morning and evening.

It also allowed them fuel, light, attendance, culinary utensils, linen

and crockery for their kitchen and dining room at Telegraph Street.

"They themselves provided their dinner".

The Ladies of the Instrument Gallery

at the Electric Telegraph Company general offices

in Telegraph Street, London

The employment of women as clerks by the Electric company was

publicly advocated by its original director and largest shareholder, G

P Bidder, initially as a cost-saving measure. The success of this

innovation in both cost-saving and in public goodwill was reflected in

the general employment of women, or rather 'ladies', as clerks both at

their counters and in their back-office galleries by all subsequent

domestic telegraph companies. The London District company, in

particular, depended entirely on a female work force.

Employment in the Telegraph Industry 1861

Analysis of the Census by Leone Levi 1865

Men................................Age 10 – 15..............493

.......................................Age 15 – 20..............862

.......................................Age 20+...................1,044

Male Total.......................................................2,399

Women...........................Age -15.....................2

.......................................Age 15 – 20..............61

.......................................Age 20 – 25..............100

.......................................Age 25 – 30..............33

.......................................Age 30+...................17

Female Total....................................................213

Census Total 1861............................................2,612

Census Total 1851............................................261

As this data is drawn from census forms

filled-in by door-to-door enumerators

in 1861 the statistics are shown for

the purpose of showing approximate divisions of sex and age. In fact

the Electric and the Magnetic companies alone employed 2,638 people in

1859, without counting those working the railway telegraphs.

In December, 1858, a great political meeting was held one evening in Manchester. The 'Times' paper, in giving a report of that meeting afterwards, said: "It is only an act of justice to the Electric and International Telegraph Company, to mention the celerity and accuracy with which our report of the proceedings at Manchester on Friday night was transmitted to the 'Times' office. The first portion of the report was received at the telegraph office at Manchester at 10.55 on Friday night, and the last at 1.25 on Saturday morning. It may be added that the whole report, occupying nearly six columns, was in type at a quarter to three o'clock on Saturday morning, every word having been transmitted through the wire a distance of nearly 200 miles. Some of our readers may be surprised to hear that this report was transmitted entirely by young girls. An average speed of twenty-nine words per minute was obtained, principally on the printing instruments. The highest speed on the needles was thirty-nine words per minute. Four printing instruments and one needle were engaged, with one receiving clerk each, and two writers taking alternate sheets. Although young girls in general do not understand much of politics, there was hardly an error in the whole report."

In 1854 the Electric company had employed Mrs Maria Craig as "Matron" in charge of the lady clerks at Founders' Court. Mrs Craig made herself available every Saturday between 2pm and 4pm at the Central Station to interview the very many young ladies seeking employment. When taken on they were trained in the basics of telegraphy in classes of six on a pair of needle instruments by her in her room.

In that year, 1859, in London there were ninety women employed at the Electric's station at Founders' Court, eight at Charing Cross in the West End, two at Fleet Street and two at Knightsbridge.

Demand for the work was such that, in 1860, Maria Rye established the Telegraph School for Women at 6 Great Coram Street, London; one of several organisations she established to further female employment. Rye had previously published 'The Rise and Progress of the Telegraphs' in 1859. The secretary of the Telegraph School was Isa Craig, the Scottish poetess. Rye in her writing thanked the Electric Telegraph Company for "the liberal manner and practical form in which they have viewed the important question of female labour".

Women clerks were repeatedly recorded as being much preferred by the public in comparison to the "insolent boys" that had been previously employed behind the counters. So much so that during the 1860s the companies' belle télégraphistes even had a popular music-hall song written about their magnetic charms.

The Telegraph Song

George 'Champagne Charlie' Leybourne

'With a tap, tap, tap and a click, click, click'

'All day they sing and laugh'

'With a click, click, click and a tap, tap, tap'

'As they work at the telegraph'

The Submarine company, which handled continental traffic, did not employ women; similarly the Electric's Foreign Gallery was worked entirely by male clerks.

Many telegraph offices in Britain continued to be located in regional stock and produce exchanges in the larger cities, as the bulk of 'public' messages were actually related to business and news; others were often, but more accessible to the real public, within city hotels. In London the District company's stations were simply rented counter space in all manner of shops, where the sole telegraphic employee was almost always a woman working long hours.

A glimpse of the internal working of messages and the employment of women comes from a brief civil court case before the Oxford Assizes. A farmer dealing in strawberries at Covent Garden market on the early morning of July 17, 1861 found the weather poor and no one buying, he wished to inform his wife in Bath not to send more boxes of fruit by the railway to London as they would not sell. He called at the Electric Telegraph Company's office at Charing Cross at about 8 o'clock and was advised that a message to Bath would be received in about fifteen minutes. The farmer wrote out and sent his message. Unfortunately it took an hour and by then his wife had already sent more boxes of strawberries to London. He claimed breach of contract and £3 compensation for unsold spoilt fruit.

The Company took this suit seriously as it challenged their long-established indemnity against omissions and errors. In its evidence it demonstrated the progress of the message through its system: it was sent from the Strand to Founders' Court at 8.25 and received at 8.31. There the problems started. The message was only sent from Lothbury at 9.15, that is after a forty-five minute delay, and received in Bath at 9.18. It was delivered by messenger over a quarter of a mile at 9.25. The Company explained the delay as follows; at Founder's Court at 8.30 there were three other private messages queued in front of the strawberry one, these took ten minutes in transmission, there were also a series of mysterious service messages on the circuit to Bath. Then at 9 o'clock the day shift took over from the night shift; all of the men working at night had to leave the Telegraph Gallery before the women, who only worked during the day, could enter the room and go to their instruments – this exchange took about four minutes.The Company won. The Court found it had no contract for service with the sender and had done all it sensibly could to progress the message. One of the influences seems to have been the introduction of several of the Company's "young lady" clerks from London as witnesses; something the rustic bench of judges in Oxford were unused to. They were singled out for congratulations on the "great distinctness and propriety" of their evidence. The presiding judge observed that he did not know whether the "young ladies" were good clerks or not but they certainly made the best witnesses.