6. THE UNIVERSAL TELEGRAPH

The Lost Future of Telegraphy

Charles Wheatstone's Universal Telegraph

The world's first electric telegraph made for ordinary people to use

in their offices, workplaces and homes; the first instrument

to interconnect private subscribers through hubs or exchanges.

Patented in 1858, perfected by Augustus Stroh in 1863

The Complete Letter Writer

Mr Punch predicts…

"Since the electric telegraph is being extended

everywhere, we think it might be laid down, like the water and the

assessed taxes, to every house. By these means a merchant would be able

to correspond with his factors at sea-towns - a lawyer would

communicate with his agents in the country - and a doctor would be able

to consult with his patients without leaving his fireside."

"What a revolution, too, it would create in the polite circles! Mrs.

Smith, when she was giving an evening party, would 'request the

pleasure' of her hundred guests by pulling the electric telegraph, and

the 'regrets' and 'much pleasures' would be sent to Mrs. Smith in the

same way."

"This plan of correspondence would have one inestimable blessing - all

ladies' letters would be limited to five lines, and no opening

afterwards for a postscript. If this plan of electric telegraphs for

the million should be carried out, the Post Office will become a

sinecure, as all letter-writing would be henceforth nothing more than a

dead letter. In that case it might be turned into a central terminus

for all the wires; and any one found bagging a letter by means of false

wires should be taken up for poaching."

December 5, 1846

Introduction

If little has been written about public telegraphy in

Britain, then scarcely anything is recorded about private telegraphy;

connecting individuals or houses by a wire for their sole use. This is

all the more surprising given that one-fifth of all telegraph

instruments in 1868 were in private circuits.

Before dealing with the history of the Universal Private Telegraph Company, which revolutionised telegraphy in Britain, some context is necessary. This entire section is particularly elaborate as none of the detail has been previously recorded in one place.

On the same day, June 2, 1858, as he obtained his patent for the automatic telegraph

which was to revolutionise public telegraphy Charles Wheatstone

acquired a patent for the components of what he was to call the Universal telegraph,

a device he uncharacteristically promoted on a personal level. The

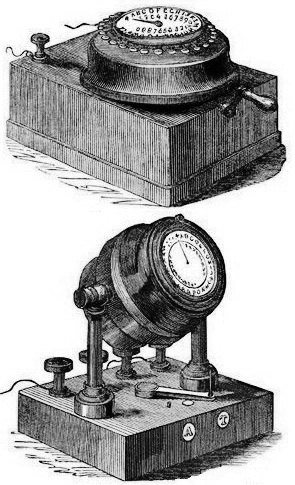

instrument, with two compact dials, the communicator and the indicator,

did not require galvanic batteries and, as it indicated individual

letters and numbers by means of a rotating needle, could be worked by

anyone who could read in perfect safety. Two instruments in circuit was

the most effective arrangement, but using up to four was possible on

short lines.

On the same day, June 2, 1858, as he obtained his patent for the automatic telegraph

which was to revolutionise public telegraphy Charles Wheatstone

acquired a patent for the components of what he was to call the Universal telegraph,

a device he uncharacteristically promoted on a personal level. The

instrument, with two compact dials, the communicator and the indicator,

did not require galvanic batteries and, as it indicated individual

letters and numbers by means of a rotating needle, could be worked by

anyone who could read in perfect safety. Two instruments in circuit was

the most effective arrangement, but using up to four was possible on

short lines.

In this patent he gave careful credit to W F Cooke as his

co-devisor of the earlier galvanic dial or index telegraphs that

inspired the Universal telegraph.

The first galvanic dial telegraph using as a receiver a disc rotated by clockwork, regulated by an electrically-controlled escapement, contained in a clock-like mahogany case, and as a sender a small capstan making and breaking a circuit was patented by Cooke and Wheatstone as far back as January 21, 1840. Cooke gave entire credit to Wheatstone for its invention, and was, unfortunately, dismissive of its commercial potential.

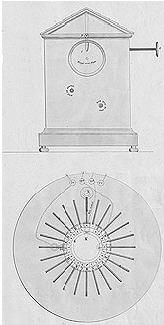

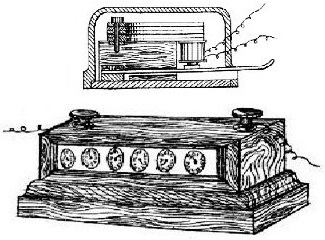

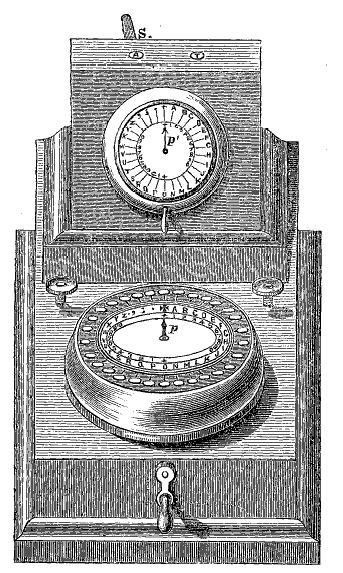

Wheatstone's patent galvanic dial telegraph 1840

Turning the capstan at the bottom rotated a disc in the small dial at the top

The receiver and its alarm were clockwork, and it needed batteries

The same patent of 1840 also included an improved dial telegraph, entirely replacing the capstan and galvanic battery with a metallic wheel or dial working a magneto device. Gently turning the wheel generated pulses of electricity that allowed the disc to turn step-by-step to each letter or number.

This electro-magnetic telegraph, as it was then called, was first used on the short line by the side of the Great Western Railway between Paddington and Slough, alternately with the original two-needle apparatus in 1843 until 1845, and on the London to Portsmouth line for a short period in 1845. It was also adopted by the Chemin de fer Paris à Versailles in 1845 and used on its line until the late 1850s. The Electric Telegraph Company allowed Wheatstone access to its circuits to further his development of the dial telegraph in 1846. It was widely copied and improved in Britain and abroad but was brought to perfection in Wheatstone's Universal telegraph of 1858.

The Universal Telegraph, the name he carefully chose, able to connect private individuals, ordinary citizens rather than technicians, was to be Charles Wheatstone's main preoccupation for a decade.

Wheatstone had introduced the galvanic dial telegraph to the public in 1840 and the magneto dial telegraph in 1842. It had been his intention even from that early date to create an instrument that ordinary people might use with facility and safety. In his arrangement with W F Cooke in April 1843 Wheatstone specifically retained to himself the rights for telegraphs with circuits of one mile or less in length, for a "district establishment" and for "domestic and other purposes". The rights expired without formal use along with the 1840 patent in 1854.

Wheatstone's patent magneto-electric dial telegraph 1840

The wheel on the box generated pulses of electricity to release the

escapement of the clockwork of the dial. No batteries!

It might be noted that the Royal Navy's messages from Somerset House and the Admiralty carried to its yards and docks at Portsmouth and Plymouth in the west by the Electric company and to Deptford, Woolwich, Chatham, Sheerness, Deal and Dover in the east by the Magnetic's circuits were on leased circuits and were worked by the telegraph companies' clerks not navy personnel. Most of these official messages were in numeric cipher and the clerks were deliberately kept ignorant of the key used. The instruments used were "locked" for security.

One of the earliest private telegraph networks was that created for the collieries of the Earl of Crawford & Balcarres at Haigh and Aspull, near Wigan, in Lancashire in 1851. By January 1852 there were nine instruments in circuit at Haigh, managing the coal traffic from the pits down four inclined tramways, one being 1½ miles in length, to the near-by canal and railways. The code used allowed the signalling of different qualities of coals for different destinations, and had been developed by the Earl himself. The colliery telegraph was just then being extended with new circuits from Haigh to the Earl's Upholland Colliery at Rainford, nine miles distant, and from Haigh and Upholland to Wigan, alongside of public railways and private tramways. The system was installed by W T Henley and used a single-needle version of his magneto-electric apparatus and gutta- percha insulated subterranean copper wires. It did not extend underground into the pits.

The Haigh Colliery was an advanced enterprise. As well as its extensive tramways and the telegraph, its engineer, William Peace, was to introduce the mechanical coal-cutter, an endless-chain driven by compressed air, in December 1853, to supplement men and picks.

Wheatstone's galvanic dial telegraph 1855

Still with the capstan transmitter but now using electricity from cells

to move the index on the dial on the right step-by-step without clockwork.

This was sold by scientific instrument makers for educational use.

On July 30, 1862 George Warren, then age 23, was appointed Court Telegraphist, a new title recognising the duties of the travelling clerk attached by the Electric Telegraph Company to the Royal Household. He replaced James Hookey, telegraph clerk to the Queen, who had been promoted to Inspector of Works in the West Midlands. Warren had joined the Company in May 1855 and had been first appointed to the Court Telegraph Office in 1861. He travelled with the Queen between Buckingham Palace in London, Windsor Castle in Berkshire, Osborne House on the Isle of Wight and Balmoral Castle in Scotland, working the Royal Household's private wires in those places leased of the telegraph company, and followed her overseas, having to be "experienced in telegraphing in French and German as well as the English language." Although board and lodging were provided wherever the monarch was staying Warren, a native of Wareham, Dorset, had a house at Cowes on the Isle of Wight. He received a salary of £154 a year with allowances for travel and board, paid by the Electric company's South Western District in Southampton, then by the Post Office. When George Warren died in 1896 the Queen had a monument placed on his grave "as a mark of regard for faithful and zealous service" after 34 years service as her private telegraph clerk.

The Royal Italian Opera House in the Haymarket, a place of popular

fashionable resort in London during the 1850s, had its own telegraph in

the lobby of the Grand Tier from May 18, 1853; connected to the

Electric's Charing Cross office in the Strand. The telegraph company's

clerk received and posted important Parliamentary news for the Opera's

patrons and was able to send messages out to the provinces. It is

difficult to think of this as anything other than a publicity exercise,

but it was still in use in 1867.

The Crystal Palace exhibition hall in Hyde Park in 1851 had its own telegraph between its many galleries and its entrances put in by the Electric Telegraph Company.

In May 1852 the Bank of England in the City of London installed a

complex internal electric telegraph system between the Governor's

Room and the chief accountant, chief cashier, secretary, engineer and

other officers using G E Dering's patent single-needle instruments.

To give some idea of period thoughts on implementing private telegraphy the original prospectus of the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company in April 1853 "offered private wires for government departments, public companies or private mercantile establishments at an annual rent of from £2 to £3 per mile per annum, a single wire giving perfect secrecy at one-half the cost of regular bills". The company intended to lay an extra fifty wires for this purpose between the main cities. The plan was never carried out.

Waterlow & Sons, a large firm of law stationers, letterpress and lithographic printers with government contracts, had the first commercial private line constructed between 24 Birchin Lane and their works at 66 London Wall in the City of London in September 1857. It was engineered by Owen Rowland, of 5 Suffolk Lane, City, EC, one of W F Cooke's earliest collaborators, using single- needle galvanic instruments, alarm bells and a single roof-top iron wire in one 1,500 foot long span for just £35. The alternative of an underground circuit was costed at £1,200.

Owen Rowland had conducted trials of both steel and iron telegraph wires on Hackney Marshes to determine their strength and durability in 1858. He used tough steel wires protected by a coating of paint, “peculiarly adapted for the purpose”, on the over-house circuit for Waterlow and also for the first private wire created using Wheatstone’s Universal telegraph, for Spottiswoode, the Queen’s Printer, which he also engineered.In the following year Waterlow's had the telegraph contractor, W T Henley, extend their little system and erect a 2¼ mile long private circuit from their Birchin Lane premises to their office at 49 Parliament Street, Westminster, near the Houses of Parliament. The new circuit consisted of two overhead iron wires (one being spare) in twelve 1,000 foot long spans running along the river Thames, and crossing it twice. The short wooden poles carrying two insulators were mounted in specially-designed iron saddles secured on the ridge of the fourteen roofs by six substantial screws, and held in place by guy wires. The No 14 gauge line-wire was manufactured of steel and covered with four coats of paint as protection against the elements. The single-needle instruments used in Waterlow's system each cost £5, and the bell alarms £4 4s. The eleven intermediate posts were all fixed on the roofs of business premises, warehouses and breweries. The new line cost £160.

Until there was an alternative to the code-worked needle instruments and the need for liquid batteries the application of telegraphy to private use was restricted. It was not until Wheatstone and Siemens Brothers introduced their dial telegraphs using magnetos rather than cells, in 1858 and 1859 respectively, that private telegraphy became commercially viable.

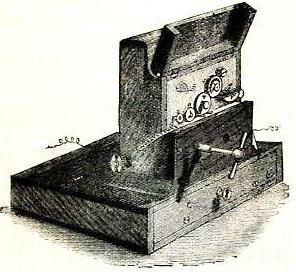

Used by the reporters of the daily newspapers to send messages from

Westminster to their offices in the Strand and Fleet Street, February 1859

Seeing the opportunity that private wires

offered, the London District Telegraph Company, on its promotion in January

1859, specifically wrote into its prospectus that it would provide them for individual

and businesses in addition to its public circuits.

The City of London Police, responsible

for the small central district, should not to be confused with the Metropolitan

Police that enforced law and order in the rest of the capital, whose chief

office in Scotland Yard had been connected to the Electric’s national circuits

with a private wire for a short period between 1851 and 1852. It was not until

1866 that the Metropolitan Police commenced their own network.

The iron ship-building yard of John Scott-Russell & Company at Millwall on the Thames in London engaged S W Silver & Company to construct a unique private telegraph to co-ordinate the installation of the machinery and the final fitting-out for sea of the mighty Great Eastern, the largest ship in the world, between February and September 1859. Using Wheatstone's Universal telegraph instruments it consisted of an underwater india-rubber insulated cable running from the hull of the great ship, floating off Deptford after her launching in January 1858, across the river Thames to Scott-Russell's works, along the length of the river-front shipyard, then underground to the separate engine-building shops and to the management and drawing offices on the Isle of Dogs. It is notable, at least to those of a sentimental disposition, that, given her epic contribution to intercontinental cable-laying, an umbilical submarine telegraph cable was facilitating the birth of the Great Eastern.

The Universal Telegraph

"The wire of one friend may be placed in communication with that of another, or in fact with any person who rents a wire. It may be that the friend may dwell in another part of the kingdom, in which case before sending a message, it would be necessary to have his wire placed in connection with a public railway telegraph, and this again at its terminus with the friend's wire."

"By combining beforehand different lines in this manner, two different persons may converse together across the island, sitting in their own drawing rooms; nay, only by extending the connection of these lines with the submarine cables across the seas, a person may converse with his friend travelling day by day at the other end of the globe, provided only that he keeps on some telegraphic line that is continuous with the main electric trunk-lines of the world."

"This may appear to be an idle dream, but that it will certainly come to pass we have no manner of doubt whatever."

Andrew Wynter, MD, 'The Nervous System of the Metropolis',

in 'Our Social Bees', 1861

The Universal Private Telegraph Company

The

Universal Private Telegraph Company was projected on September 20, 1860

to acquire Charles Wheatstone's patent of 1858 for his perfected

magneto- electric dial apparatus, the easily-operated Universal telegraph,

a small, neat instrument, to "carry out a system by which banks,

merchants, public bodies and other parties may have the means of

establishing a telegraph for their own private purposes from their

houses to their offices, manufactories or other places". Its initial

incarnation was as "The Universal Private Telegraph Company, Limited",

incorporated under the new Joint Stock Limited Liability Act of 1857.

It then sought a capital of £50,000 in 500 shares of £100 during

October 1860, and had just two directors, Professor Charles Wheatstone

and William Fairbairn, CE, the Manchester ironmaster. The Company's

officials were Thomas Page, engineer, Lewis Hertslet, secretary and

Nathaniel Holmes, electrician. It was almost immediately found that

parliamentary powers were needed to facilitate its laying of wires over

public roads, in addition to negotiating with parochial authorities in

towns and cities for access and wayleaves, and that a broader capital

base was required to ensure its viability.

Despite this the Limited Company was immediately active in marketing itself in Glasgow, rather than London. The first announcement of its services appeared there on April 10, 1860, in a very long descriptive article written for the 'Glasgow Herald' by Nathaniel Holmes. This was followed up by another on October 11, and by the publication of the prospectus for the Limited Company on October 17, 1860. Holmes was then living in Carrick's Royal Hotel on George Square in the city.

However, Holmes and the Universal company had already been busy in London as the second Scottish article, on October 11, revealed that both Julius Reuter and the City of London Police had networks of private circuits working by then.

It announced on October 17, 1860 that "The main object of this Company is to enable the Government Offices, Police Stations, Fire Stations, Banks, Docks, Manufactories, Merchants' Offices, and other important Public and Private Establishments to have a private system of communication with their own Establishments and Manufactories at distances, either from their offices or residences, by means of Professors Wheatstone's new and valuable Patents, which combine such simplicity that anyone who can read and spell can work them without difficulty, thus affording each establishment a distinct wire and private means of communication exclusively their own. The Company will either erect and maintain such Telegraphic communication at a fixed annual rental, or charge a specific sum for each contract for a term of years, as may be agreed upon."

"It is intended to extend this system of private Telegraphic communication beyond the limits of the Metropolis to other important cities, as Glasgow, Manchester, Liverpool, Birmingham, Preston, Bristol, Hull, Edinburgh, Nottingham, Plymouth, &c., additional capital being added from time to time for such purposes."

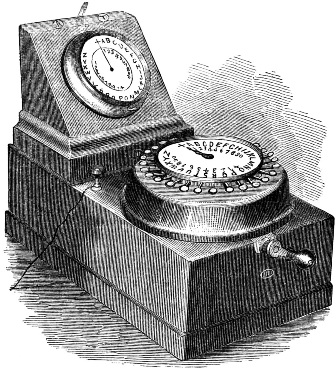

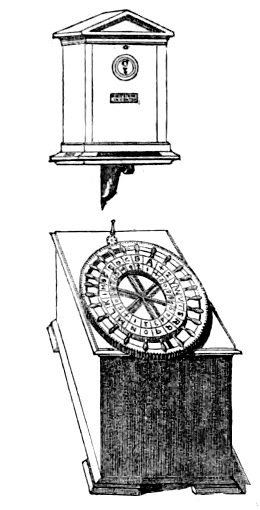

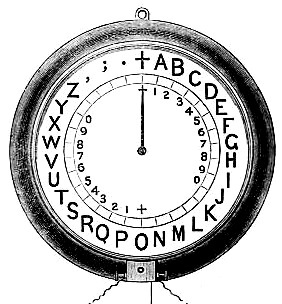

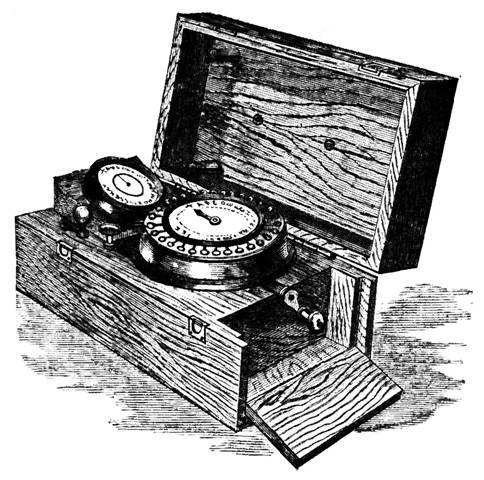

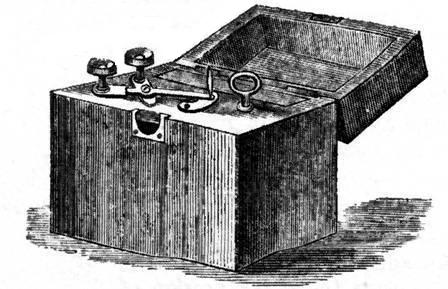

The original Indicator of the Universal Telegraph in 1859

Called the "coconut" from the shape of its wooden dial housing

The switch on the base: "A" for Alarm, "T" for Telegraph

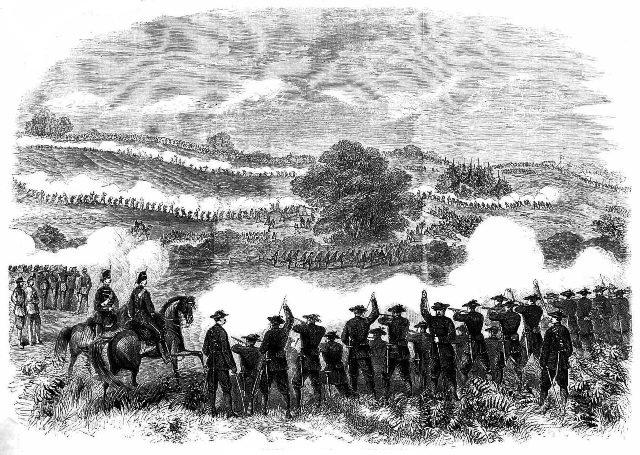

Even before this Nathaniel Holmes had been to War on behalf of the Universal telegraph. The 'Illustrated London News' of July 21, 1860 carried a long report on "Professor Wheatstone's Universal and Military Telegraph":

"This beautiful telegraphic apparatus, invented and patent by Professor Wheatstone, possesses great advantages over the many existing telegraphs from its extreme simplicity, portability and adaptability to all the various purposes for which communication may be required. The necessary qualifications for a complete telegraph were fully demonstrated by its arrangement upon the field under Mr N J Holmes, the electrician, at the volunteer sham fight at Camden Park, last Saturday [July 14, 1860]. Insulated lines of wire, payed off from portable drums, were extended over the ground from the central station in front of the grand stand to the divisions severally under the command of Lord Ranelagh and Colonel Hicks, forming terminal stations, which were afterwards moved over the ground as the volunteer forces shifted their positions, conveying intelligence of their movements from one division to the other, the whole of the evolutions being known to the central station at the grand stand. The instruments work with a single wire insulated by a coating of india rubber and covered with braided hemp as a further protection from injury and abrasion by the tramping of men and horses over it upon the ground, the earth connection being formed by the insertion of an iron spade or trowel attached to the wire into the ground and shifted as required."

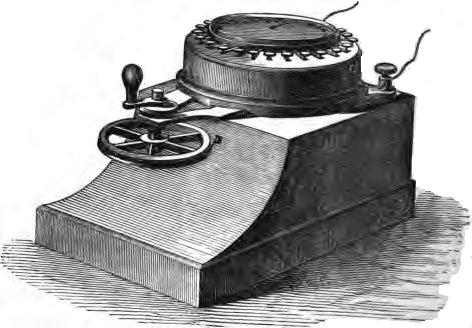

"The telegraph consists of two distinct portions – the transmitter, or communicator, for sending; and the receiver, or dial, whereon the message is read. The communicator is a small box about one foot long by six inches deep by eight wide, upon which the twenty-six letters of the alphabet are engraved, together with the points of punctuation, and the cross or signal for the termination of words and messages. Opposite to these thirty spaces corresponding buttons are placed round the dial, each button representing the letter or sign annexed to it, so that messages are spelt out by generally depressing in succession the requisite buttons or letters composing the word, each separate word being marked by the depression of the cross. A pointer at the centre of the dial, when the telegraph is in action, revolves, and stops at the depressed button, the action of which will be presently explained. The interior of the box contains a permanent magnet, from which an induced current of magneto-electricity is obtained when required by the revolution of a small soft-iron armature and helix placed before the poles of the magnet, in close proximity, but not in contact. This armature by induction becomes itself a magnet in certain positions, and during its revolutions is continually parting with its charges and receiving fresh supplies, the several currents generated in this way being transmitted through the communicator and keys to the distant station along the wire. The revolving motion is communicated to the armature by the exterior handle and hand of the operator. The second or receiving portion consists simply of a small round barrel or dial, upon the face of which similar letters are engraved, to correspond with those of the transmitter; a hand or pointer on the dial, set in motion by the direct action of the current from the distant station points out the letter to be read off by stopping for an instant before it passes on to the next in succession composing the word. So rapidly are these indications received that over one hundred letters a minute may be read off with ease."

"The action of the instrument may be briefly explained as follows: Any letter, as H, being depressed upon the communicator, a certain number of distinct magneto-currents will be transmitted down the line to the distant station by the revolution of the soft-iron armature, each of which will register an advance of the pointer a letter upon the dial at that station. Now, as there are eight spaces between the cross or starting-point and the letter H, there will be eight currents, or eight advances of the index, which will stop at H, the current from the magneto machine being cut off from the line, and passed into the earth by the hand coming into contact with the depressed button. When another button is depressed the former key is raised and the currents again pass down the line until cut off by the hand as before, the index upon the distant station advancing as before, and so on, until the message is completed."

The Volunteer Sham Fight, Bromley, Kent 1860

A mock battle with 6,000 riflemen co-ordinated for the first time

by Wheatstone's Universal field telegraph

The Volunteer Sham Fight took place at Camden Park, Bromley, Kent, on Saturday, July 14, 1860. It was intended as a mass field exercise for the newly formed Rifle Volunteer Corps in the metropolitan boroughs. To give some idea of its size there were, according to the 'Daily News', an estimated 25,000 spectators in the grandstand and on the park grounds. The troops comprise two "attacking" brigades and a defence, nearly 6,000 men in all: the first brigade, 1,300 strong, composed of three battalions, drawn from the Rifle Volunteer Corps in Middlesex, Surrey and Tower Hamlets, the second brigade, although also of three battalions, was even larger, from Kent and Middlesex. The defenders came from Corps raised in the City of London, Middlesex and Kent.

The South Eastern and West End of London & Crystal Palace Railway companies offered the volunteers a bargain return fare of 8d from the London Bridge and Pimlico termini in London to Southborough Road for Bromley. James Wyld, the Queen's geographer, prepared maps of the ground and of the anticipated military evolutions for the assistance of visitors.

The public assembled by 3 o'clock in the afternoon; although intended to commence at 5 o'clock it was not until 7 o'clock that the battle got underway, lasting two hours. By 10 o'clock the volunteers were marching out of the ground. The railway was still carrying off volunteers and visitors at 2 o'clock the following morning.

The 'Daily News' enthusiastically reported the use of "Professor Wheatstone's field telegraph" and Holmes' presence by the grandstand. It mentioned that Lord Ranelagh had used the telegraph in the delay to summon "Herr Schallehn with his accomplished artists of the South Middlesex band" from the front line to amuse the lady spectators.

The government, which was hostile to the Volunteer Rifle movement, had promised provisions and cooking stoves, but provided none. This meant that many of the volunteers went for fourteen hours without food in travelling to and from and engaging in the sham fight.

Napoleon III, Emperor of the French, had already created a télégraphe volant or"Flying Telegraph" to accompany his army when it expelled the Austrians from Savoy in northern Italy during June and July 1859. The field cables, laid from horseback, were bought from the Gutta Percha Company and Wheatstone's new instruments from the Universal Private Telegraph Company in London.

The original Communicator of the Universal Telegraph in 1859

Lightly pressing one of the keys stopped

the rotating needle on the inner dial, as it was propelled round by a hand cranked magneto

The next campaign on behalf of the Universal telegraph was led by a promotional visit for journalists to Julius Reuter's premises in the City of London on the morning of Friday, December 21, 1860, conducted by Holmes. The major London morning papers published detailed, favourable reports of the new Universal apparatus, its overhead cables and its costs. These reports were copied over the next week by the main provincial daily and weekly journals.

It was not until April 8, 1861 that the first paid advertisements in the 'Times', the 'Daily News' and the other London morning papers appeared, promoting its terms of £4 per mile of wire and the option to buy or rent instruments. These coincided with a demonstration of "Professor Wheatstone's Universal telegraph" at the Royal Polytechnic Institution at 309 Regent Street in London's West End during that month.

The Company obtained a Special Act of Parliament for its statutory incorporation on June 7, 1861, with a capital of £100,000 in 4,000 shares of £25, half of which was called-up, and to acquire powers to erect and maintain private telegraph wires at a fixed annual rental and provide the instruments necessary to work them. The promoters modestly anticipated a minimum net dividend of 10% per annum. The new Statutory Company was launched on November 18, 1861; as Wheatstone's Universal telegraph had been introduced in 1858 there were already a large number of private circuits in use in London and in Glasgow.

Initially 2,000 shares were issued and taken up, mainly in London; eventually calls were made for £20 on each of these from 1861 through to the end of 1862. This would provide a working capital of £40,000 to finance and extend its first circuits in London and Glasgow.

The Universal company initially took rooms for its secretary and its clerks at The Estate Market, 3 Hanover Square, London W, a newly redeveloped building, formerly a hotel, with offices and chambers, as well as a board room, to let. Lewis Cooke Hertslet, the Company's secretary was also Manager to the Estate Market, owned by Mark Markwick, a property auctioneer. It was not there long, and had moved to 448 Strand, in rooms above the Electric Telegraph Company's Charing Cross station, by December 1861.

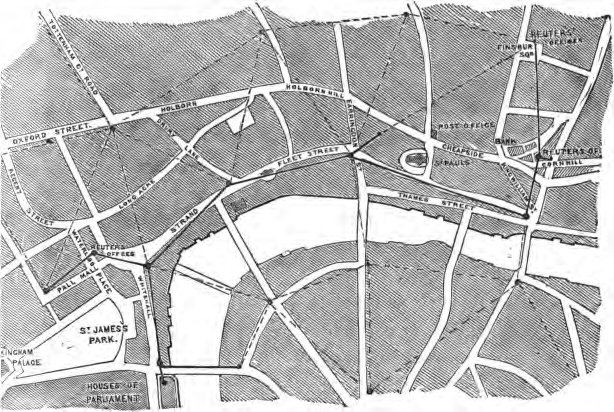

By June 6, 1861 there was already an aerial cable in operation between Finsbury Square and the Royal Exchange, containing 24 miles of wire, and another from the Royal Exchange along Fleet Street and the Strand to Waterloo Place, with 158 miles of wire, each wire ready to be connected to a private subscriber. In progress were lines from Charing Cross to the Houses of Parliament, 42 miles of wire, and from Waterloo Place to Camden Town, the Goods Depot of the London & North Western Railway, containing 45½ miles of wire.

The Universal company had a Board of eight directors; chaired by David Salomons, chairman of the London & Westminster Bank, the country's largest financial concern, among whose directors was J L Ricardo. The Board had, too, at its table, Charles Wheatstone – his only directorship and by far the largest shareholder. It also had the remarkable scientific weight of his friends and colleagues, Joseph Carey, William Fairbairn, and Edward Frankland. Latterly the active directors were: Frederick C Gaussen, Robert O'Brien Jameson and C Wheatstone. Its Secretary was Lewis Cooke Hertslet, a professional manager, and its electrical engineer was the ubiquitous Nathaniel J Holmes, who was also active in canvassing support among the scientific community at Wheatstone's behest. Holmes had been the original London station manager of the Electric Telegraph Company in 1846, working with Wheatstone in the 1850s and became engineer to cables and land lines in Europe and Asia.Among the largest of the shareholders in the earliest days were S W

and H A Silver, the manufacturers of india-rubber cable insulation, and

William Reid, the second largest shareholder, principal of Reid

Brothers, the telegraphic engineers and contractors, long associated

with Charles Wheatstone in making his instruments. The Reid family

retained their considerable interest until the end in 1870 when there

were six, men and women, holding shares. Holmes had one share in the

Company.

The prospectus noted that its bankers, where deposits for shares ought to be made, were the Union Bank of London, Temple Bar branch, the Manchester & County Bank and the National Bank of Scotland.

The eminent civil engineer, Thomas Page of Middle Scotland Yard, Whitehall, responsible for many major bridges, docks and sewerage works, was appointed consultant to the Company in 1860. He was not much troubled by his appointment. Page had lent his name to the alternative transatlantic telegraph cable promoted by James Wyld MP, by way of Scotland, Iceland and Greenland to Canada, in 1859, and did so again in 1866.

One of the first acts of the Board was to engage in an Agreement

with the Electric Telegraph Company, with its immense network of public

circuits; this complex seven-year arrangement was signed on September

3, 1861. Its clauses stated the strategic ambitions of the two

companies; 1] the Universal was to operate private wires in cities and

towns, it would not allow the wires of any other company on its

premises, and it was to transcribe messages from its private lines to

the public system only through the Electric's circuits. 2] In return

the Electric would accommodate the Universal's clerks and instruments

on its premises but would not be responsible for any costs. Messages

would be transcribed at the Electric's current rate and all such income

would be retained by the larger company; equally all revenues from

private lines and instruments would go to the Universal company. 3]

Unless the Electric agreed otherwise the Universal would not engage in

public telegraphy or in third party agreements for service; in return

the Electric would not engage in private telegraphy other than for

government service which it was obliged to do under its Acts. 4] The

Electric undertook to match the rate for any foreign messages

transcribed from the Universal's circuits to the lowest available.

Private subscribers were only able to specify another company's foreign

route if were to be quicker to the destination. However, foreign press

despatches and newspaper messages could be sent by any route or

company. 5] The Electric Telegraph Company agreed "to support and

assist the Universal Private Telegraph Company, other than by pecuniary

means".

The two companies clearly demarcated their spheres of

work, and anticipated transcription traffic from private to public

circuits, co-operating to achieve this. There was to be no

revenue-sharing or inter-company discounting. The early importance of

private press messages was highlighted in concessions.

The Company opened its chief office at Charing Cross, the geographical centre of London, initially within, then as it expanded to offices next door to, the Electric Telegraph Company's West End station, at 448 Strand, so that private messages could be transcribed from private to public circuits and vice versa by the hub station. Instruments in offices and houses were hence able to connect with the entire domestic and foreign telegraph system. It paid the Electric company £100 per year rent for "an office".

Eventually the Universal Private Telegraph Company was to have its principal office at 4 Adelaide Street, West Strand, housing the secretary, the engineer and three or four clerks. Its District offices were at 15, later at 11, St Vincent Place, Glasgow; at Hartford Chambers, St Ann's Square, Manchester, and then, from 1864, at 52 Brown Street, Manchester; and at Printing Court Buildings, Akenside Hill, Newcastle, each managed by a Local Secretary and two or three clerks. With such a small workforce the firm relied heavily on contractors for originating all of its services, whether constructing its lines or providing instruments, for maintenance and for storing materials. The prime role of its few clerks was in billing and accounting. The only other staff members were the Engineer, the Assistant Engineer and two local "line assistants".It was reported that each of the three District offices in the provinces had “stores” for instruments and apparatus. No record of such premises has been found, so they are likely to have been in the nature of a “cupboard.”

In 1864 it also advertised offices in its own name at Dundee in Scotland and Belfast in Ireland. These were actually the premises of its sales agents, George Lowden, instrument maker, of 25 Union Street, Dundee, and P L Munster & Sons, merchants, of 6 Corporation Street, Belfast.

Universal Private Telegraph Company's Plan for London 1860

Solid lines shewing circuits already built, broken lines planned

The three offices of Reuter's news agency indicated

Click the thumbnail above for a greatly enlarged version

(Click on Previous Page to resume)

The Company's works throughout its existence were in the hands of a

small number of suppliers: Reid Brothers were contractors for all

overhead and road works in London, Glasgow, Manchester, and Newcastle.

The Company used Reid Brothers' stores at 12 Wharf Road, City Road,

London N, as their depot for materials. The Company paid Reids £80 per

annum for "a storehouse". S W Silver & Company manufactured the

india-rubber insulated aerial cables. Where it needed wooden poles the

Company bought them from the Electric company's depot at Gloucester

Road, Camden, or, for the north of the country, from Thomas Robinson

& Son, Oldham Road, Rochdale, timber merchants.

The principal manager was the Company's Engineer, a fact of some novelty; for most of its life this was Nathaniel Holmes, with an annual salary of £600. When he became involved with other work in the mid-1860s his assistant and eventual replacement in 1866, Colin Brodie, became equally active in promoting the Company's telegraphs and dealing with the Board. Lewis Hertslet, with a salary of £300, remained as Secretary in London from 1861 until 1864 when William Brettargh, one of the Company's longest serving clerks, took over and remained in that position until 1868.

Each of the three provincial districts had a Local Committee of directors or major shareholders of five or six members that managed the business. As with the Board in London these were assisted by a Local Secretary. In Manchester this was Basil Holmes, the brother of Nathaniel Holmes, then Frederick Evan Evans; with Robert J Symington in Glasgow and Arthur Heaviside, Wheatstone's nephew, in Newcastle. The Local Secretaries had a salary of £200 per annum. Their clerks were each paid £52 a year.

Holmes was originally supported in 1861 by two "line assistants", Eugene George Bartholomew (£200 a year) and Colin Brodie (£150 a year). Bartholomew, who had previously been telegraph superintendent of the London, Brighton & South Coast Railway and superintendent at the Valentia station of the Atlantic Telegraph Company left in 1864. Brodie then became Assistant Engineer at £300 a year, and was finally to replace Holmes in 1866.

As regards the apparatus on private premises, maintenance and repair was placed in the hands of "Inspectors of Instruments", effectively sub-contracted, self-employed clock, chronometer and watch makers in the cities in which the Company had district offices. None of these individuals were employees of the Company and there were probably less than a half-dozen. The instruments, by all accounts, were remarkably reliable.The Universal Private Telegraph Company, even from its first years, was not just a provider of communications - as its presence at the International Exhibition of 1862 at South Kensington shows. The influence of Charles Wheatstone was overwhelming; of course the Company displayed to the audience two of Wheatstone's Universal telegraphs, but it also included and offered for sale examples of immensely advanced technology; his automatic printing telegraph – which it claimed could print 500 code-characters a minute; his magnetic clock connected with several other small clocks; alarm and "exploding" bells worked by electricity; and a magnetic register or telemeter, showing the number of persons passing through the doors and turnstiles of the exhibition.

The "exploding" bells were actually Wheatstone's patent magnetic exploder for detonating explosive charges. It had been advertised by the Company in June 1861, and was widely demonstrated indoors and outdoors during the 1860s by remotely letting-off small fireworks and flares. The exploder was adopted by the British Army for demolitions in 1861.

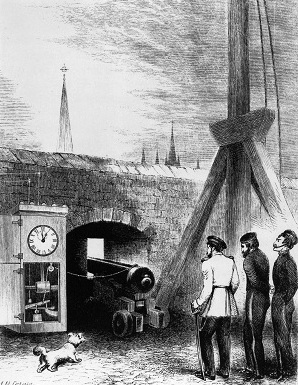

Commencing in 1863 the Universal Private Telegraph Company installed a series of 'time guns' in Newcastle, Glasgow and Belfast. These sounded the hour at one o'clock each day based on an electric time signal from the Observatory at Edinburgh, Scotland.

On January 11, 1865 Nathaniel Holmes wrote to Captain Matthew Maury from the Company's office that he was negotiating with General Sir John Burgoyne, inspector-general of fortifications, in regard to electrical torpedoes that they and Wheatstone had been developing. "Tact and delicacy" were required in proceeding to avoid revealing anything to the Americans, with whom Maury's country was at war.

In 1868 the Company was also selling cipher machines or "cryptographs", another of Wheatstone's inventions, to monarchs, governments and the police.

Developing the Business 1861

Unlike in

public telegraphy where Miles of Line are important in securing

particular profitable routes and Miles of Wire are less so as they

address capacity and to some extent are adjustable to suit demand – in

private telegraphy Miles of Wire are the determining factor in the

model. The more Miles of Wire that it rented out to private subscribers

the greater its income will be; the private wire company must determine

the optimum number of wires for any district that it intends to serve

and ensure maximum uptake of those wires. The use of multi-strand

cables was the key to effectiveness in this, rather than the multiple

use of single iron wires.

The original costs for

private telegraphy were similar to public telegraphs: in negotiating

rights-of-way, paying wayleaves, and in constructing the lines.

The Universal Private Telegraph Company initiated two income

streams; rentals from private wires and rental and sales of

instruments. During 1861 and 1862 it had constructed ten aerial cables

in London, each carrying from fifty to thirty circuits or "strands",

its marketing effort was in finding renters for each of these circuits.

It planned to buy or lease houses at triangulation points across London

to form secure places for the attachment of its aerial cables on their

roof-tops and then let the premises to businesses or residents

conditional on access to their circuits.

Even before the Company's creation the Universal telegraph instruments had been installed on internal circuits at newspapers in London, by Reuter in his foreign news agency and by the City Police.

The Company's initial twelve page prospectus, issued in 1860 from Hanover Square, revealed that the first Universal telegraph circuit had been made in the autumn of 1858 between the Houses of Parliament in Westminster and the Queen's Printers, Eyre & Spottiswoode, in Shoe Lane, Fleet Street in the City of London.

It also said that in 1860 the London Dock Company had nine instruments in operation, between its Dock House, their chief office, in Princes Street in the City of London, to the Superintendent's office at their docks at Ratcliff Highway, to the Commercial Sale Rooms in Mincing Lane and to several warehouses. The Surrey Dock Company had joined their Dock House in St Helen's Place, Bishopsgate, City with their docks in Rotherhithe, and the Commercial Dock Company their Dock House in Fenchurch Street, City, to the other great dock complex at Rotherhithe, both with two instruments. The City of London Police then had nine instruments; Julius Reuter had six, connecting his offices in Waterloo Place, the Houses of Parliament, Royal Exchange Buildings and Finsbury Square; the 'Daily Telegraph' newspaper, most appropriately, also had two, between its offices in Fleet Street and the Houses of Parliament. De la Rue & Company, banknote and stamp printers, had four, connecting Bunhill Row, Cannon Street, and the Government offices in Somerset House, Strand; Glass, Elliot & Company, the telegraph cable makers, had two, from Cannon Street to their works in Greenwich; the North London Railway had an experimental line with two instruments between its stations at Hampstead Road and Camden Road (the latter being opposite the site of Wheatstone's first line of telegraph in 1837).

Alfred Waterhouse, the proprietor of the large tea-dealing firm of Dakin & Company, was to have his home at 44 Russell Square, Bloomsbury, his City office and shop at 1 St Paul's Churchyard, City, and his West End outlet at 119 Oxford Street, linked by telegraph, acquiring four instruments.Outside of London, in 1860, Platt Brothers, textile machinery makers of Oldham, Lancashire, had three Universal telegraphs to connect their several workshops. The Forth & Clyde Canal Company in Scotland had two to communicate between their lock gate stations. Lord Kinnaird installed two, between his house at Rossie Priory and his factor's office in the City of Dundee, twelve miles distant.

There were, in addition, thirty-one commercial and industrial concerns in the City of Glasgow that were awaiting completion of the Company's first private circuits in Scotland's other capital.South Australian Railways had also bought fifty-two sets of Universal telegraph apparatus "capable of working over a distance of 150 miles" in 1860.

The earliest additional subscribers for

rental of a private wire in London included, in April 1861, S W Silver &

Company, Bishopsgate to Silvertown; Ravenhill & Salkeld, engineers and

shipbuilders, Ratcliffe to Blackwall; the ‘Daily Telegraph’, Fleet Street to Russell

Square (the owner’s residence) and the Thames Graving Dock Company, Silvertown;

in September 1861, Pickford & Company and Chaplin & Horne, the carriers,

and Bass & Company, the brewers, from their City premises to Camden Town

railway goods depot; in March 1862, J Reuter, Royal Exchange Buildings to the

offices of ‘The Times’, ‘Daily Telegraph’ and ‘Morning Star’ newspapers; and in

July 1862, the Zoological Society of London, from its premises in Regent’s Park

to its offices in Hanover Square, Middlesex Water Works and Price’s Patent Candle

Company. The famous photographic artist, Antoine Claudet, had a private telegraph

connecting his house in Chester Square with his studio at 107 Regent Street in

that month.

From its commencement the Company had a strong interest from Glasgow; almost simultaneously with the cables in London a series of circuits were established in Scotland's commercial and engineering capital.

The first contract for a private telegraph outside of London was agreed with Reid & Ewing, muslin and calico printers, of Maryhill, Glasgow, on October 23, 1860, to connect with their city office in George Street.In September 1861 the City of Glasgow Police; Loch Katrine Waterworks; the Glasgow Gas Light Company; the City & Suburban Gas Company; the Forth & Clyde Canal; Dalglish, Falconer & Company, calico printers; Henry Monteith & Company, dyers; G & J Burns, steamboat owners and engineers; A & A Galbraith, spinners and cloth manufacturers; Charles Tennant & Company, chemical manufacturers, David Hutcheson & Company, steamboat owners; Yates, Brown & Howat, muslin manufacturers; and many other mercantile, shipping and engineering firms were already subscribers. Whilst most acquired two instruments to connect their city office with their works, the ship-owners, G & J Burns required six, and David Hutcheson, four Universal telegraphs to cover all their premises.

William Mackenzie, a "letterpress printer, stereotype founder, engraver, lithographer, bookseller and publisher" of 45 & 47 Howard Street, Glasgow, had a private circuit installed between his office and works. He also engaged to print the Universal company's initial prospectus, and went on to produce the firm's stationery and instrument manuals for most of its existence.In October 1861 the Company was canvassing for private wire customers in Manchester, the centre of the cotton trade and manufacturing in Britain and was engaged in building its first aerial cables there. It appointed an Agent to solicit business on commission, Wheatley Kirk & Company, of Albert Street, St Mary's, Manchester, a firm of surveyors, valuers and auctioneers of factories, plant and machinery. Kirk, who styled himself "District Engineer & Agent", for Manchester, Lancashire, Yorkshire, Cheshire and the Midland Counties, was to be found exhibiting the telegraph to trade associations in Manchester during 1861.

Nathaniel Holmes, the Company's engineer, was the driving force in the initial development of the Universal company; he was to be found soliciting share holders from the scientific and mercantile communities, touring the country in this role as well in engineering and managing its works. In 1862 he was travelling between London, Bristol, Newcastle, Birmingham, Glasgow and Liverpool and ran up £907 in costs and expenses.

Looking for major users, during 1861 Holmes provided a costing to the Government for private circuits in Whitehall to serve fifteen cabinet ministers; 19 instruments, 11 extra bells and 4 switches, totalling £337. In the same year he quoted the Metropolitan Police for circuits connecting Scotland Yard with the seventeen divisional chief offices and to the City Police; 21 instruments, 13 bells and 4 switches, at £335. Both of these projects were to be adopted in subsequent years in slightly modified forms.

However, the Company's activities were producing results, orders for private lines in June 1862 were: in Glasgow 37; in Manchester 54; in Liverpool 15 and new lines in London 20.

In this year a substantial network was commenced for the Marchioness of Londonderry connecting her residence at Seaham Hall, Durham, with several of her collieries and the harbour at Seaham. This grew to five separate circuits by 1868, and connected with the Electric Telegraph Company at Sunderland.

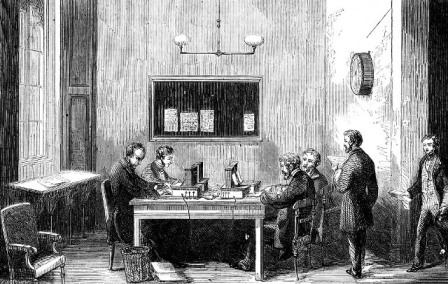

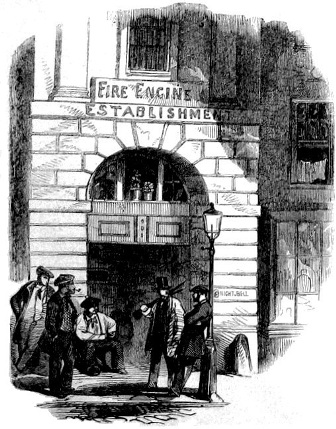

Reuter's West End Office, 9 Waterloo Place, Pall Mall, 1861

one door from Charles Street, above a firm of

Army, India and Colonial Agents

The Universal Private Telegraph Company

and Mr Julius Reuter's Establishments

The 'Glasgow Daily Herald', Saturday, August 10, 1861

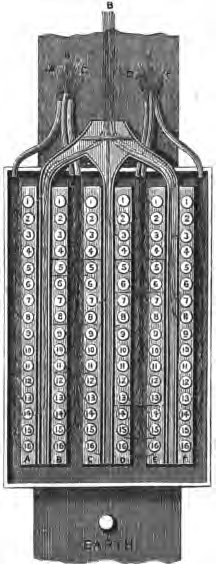

"The eye is arrested at the corner of Threadneedle Street by a

singular tripod erection upon the roof of Mr Alderman Moon's

[bookselling] premises, Royal Exchange Buildings. In appearance this

resembles one of those iron river beacons placed to warn mariners off

some dangerous shoal, with the exception that sundry ropes, supported

by iron wires, appear to diverge from the top, and spread out in

different directions. These rope-like appendages enclose the electric

conductors of fine copper wire, fifty or one hundred being combined

together according to the requirements of the district through which

the "telegraphic main" is carried. Each separate wire of this bundle of

conductors is carefully secured from contact with adjacent ones by

insulation with Messrs Silver's patent india-rubber process, and

further protected to resist mechanical injury and the effects of

atmospheric exposure by coatings of prepared tape and hemp. The rope

thus constructed is suspended between the poles, in lengths of about

200 yards, to the two iron wires by means of hooks drawn with it over

the wires. The ends of each length of rope are carried down the pole

into a box, the several wires separated and passed through little

canals of ebonite arranged in a disc, and numbered consecutively, to

correspond with those of the wires. By these means a communication with

the "main" can be opened as any point along the line, and private wires

carried down from the nearest post to the house or premises required to

be placed in communication. If any accident happens to any particular

wire, it can be discovered where the fault lies by testing from post to

post."

"Passing onwards from the Royal Exchange, the "telegraphic main" traces its path down Birchin Lane, across the tower of St Clement's Church, to Cannon Street, where it enters another tripod, and meets the lines coming in from Whitechapel, Bermondsey, and North Woolwich. These tripods are placed wherever several lines meet or fall into one another, and are intended as stations for combining the wires coming in one direction with those entering from another. The ends of these cables are carried down the post into the connecting box. The box consists of a sheet-iron frame fitted with a lid, and about three feet long by two broad, and four inches in depth. The interior is furnished with insulating slips of ebonite, corresponding in number to that of the cables entering the box. Each ebonite slip is furnished with a series of small screw terminals, numbered consecutively 1, 2, 3, 4, &c, to correspond with those of the discs along the line, and receive the several insulated wires of the rope which it represents. These wires are severally attached to the screws of each lip, and by means of cross-connection, can therefore be combined together in any desired direction. Entire command is thus given over the whole of the lines."

"By means of one of these boxes, at Waterloo Place, the various foreign ambassadors having private wires carried into that office, can, at will, be thrown in to communication with one another, the correspondence, though passing through Mr Reuter's establishment, remaining entirely secret. The various telegraph companies each having a private wire carried into Waterloo Place, any ambassador may likewise, by means of this box, at once be placed in direct communication between his own residence in London and his government abroad through the agency of the International or Submarine company's Continental system."

"Following the rope at a considerable elevation along Cannon Street, St Pauls' Churchyard, and Ludgate Hill, the line enters another tripod, at the corner of Bridge Street, Blackfriars, meeting the Holborn and Southwark "mains". Leaving this, the wires pursue their zig-zig course along Fleet Street, and the Strand, the 'Illustrated London News', and Somerset House, to Hungerford Market, where they are lost to the eye. Here, by permission of his Grace the Duke of Northumberland, the cable passes along the roof of Northumberland House, descending into the street at Messrs Prater's [army clothiers], from whence is passes underground to Mr West's, the optician, of Cockspur Street, and, re-appearing again at his roof, is carried across Pall Mall to Waterloo Place, where, for the purposes of the present description, we will leave it to worm its tortuous and various windings up Regent Street, Oxford Street, Tottenham Court Road to Euston Square, and the goods station, Camden Town. At Messrs Prater's, [No 2] Charing Cross, the "telegraph main" diverges in the direction of Whitehall and the Houses of Parliament; and by permission of the First Commissioner of Works, also passes almost the entire distance along the cornices of the Government Buildings, entering the Houses of Parliament, at the Clock Tower, and under the basements to the lobby of the House and the Reporters' Gallery.""At Mr Reuter's telegraph office, 9 Waterloo Place, the wires descend into the house; and there we propose to examine more minutely the system. On entering this establishment we proceed up a staircase, and find ourselves in a suite of handsome apartments, used for the transaction of important business."

"Ascending the stairs, we enter the signal room on the right round which, ranged on shelves, are the call-bells, twelve or thirteen in number, each furnished with a tell-tale, and numbered 1,2, 3, &c. From these bells wires proceed into the instrument room, and can be placed when required in communication with the corresponding instrument, to give notice that a "telegram" is about to be sent. As soon as any bell rings, a boy in the alarm room calls out the number to the instrument clerk, who immediately prepares for the message. Passing from here, we enter the instrument room, into which thirty wires descend from the telegraphic "main" on the roof. Eighteen of these wires branch off into a box fitted with terminable screws placed in the instrument room, the remaining twelve being carried into a similar box in the ambassadors' room. At these boxes the ends of the wires are all numbered to correspond with those in the "main". From these boxes, also, another series of wires proceed to the various instruments ranged round the room, by which means the ends of a wire, at any particular instrument, can at any moment be thrown into communication with any of the thirty wires leading into the "main". Standing in the centre of the room, we have time to examine more closely the details of this wonderful arrangement; and the first thing that strikes us is, that each of the instruments has a plate attached to indicate to which direction of the metropolis it is in communication. On one we can read 'Times', Printing House Square; on others 'Times', Houses of Parliament; 'Daily Telegraph', Houses of Parliament; &c., other tables enumerate the 'Daily News', 'Morning Post,' 'Morning Herald', 'Morning Star', 'Morning Chronicle', 'Morning Advertiser', each of the various newspapers having its own private representative, and distinct channel of news. Other series of tables and instruments point out fresh sources of intelligence – wings of thought by which the genius of the house, Mr Reuter, carries on his business. Here we read Reuter's Cornhill, Reuter's Houses of Parliament, Reuter's Finsbury Square. Then again there is the representative from the International Telegraph Company, standing in the room ready for the instantaneous receipt of the Continental Service "telegrams"; messages can be received here simultaneously with their despatch from the Continent. Here, indeed, the mind seems bewildered at the comprehensiveness of the arrangements and system, which can, at a grasp, place an individual not only in complete command of the Continent, but also of the metropolis, and almost every important town and sea port in the United Kingdom."

"The power and resources of this little room are almost fabulous. Presently one of the alarms rings in the next room, and without further preparations, beyond shifting a handle to throw the telegraph into connection with the "main", the little index in front of the operator revolves with marvellous rapidity, and the words, "Paris, July 29, evening. It appears that the king of…" just catch our eye as we retire, amazed to think that the quiet house in Waterloo Place is in exclusive possession of intelligence that only a few moments before was whispered in Paris."

This extract is quoted in such length as it describes the remarkably sophisticated private electric communications system that the Universal company and Julius Reuter had together developed in 1861!

Reuter's offices at Lothbury and Finsbury Circus were said to be equally complex in their arrangements. Nathaniel Holmes, the Company's engineer, provided access to Reuter's Waterloo Place hub, and was the guide during the tour. He may have written this revealing, indiscrete article.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

The Year 1862

After a year’s construction activity the

Company had achieved in September 26, 1862, in miles of wire constructed in cables,

with the number of strands (circuits available) and those miles of wire that it

had found renters for:

London District 1862

Line A – Finsbury, 30 strands, 1 mile

length, 30 miles wire , 9 ½ miles rented

Line B – Strand, 50 strands, 3.2 miles

length, 160 miles wire, 51 miles rented

Line C – Whitehall, 50 strands, 1,200

yards length, 35 miles wire, 6 ½ miles rented

Line D – Camden, 30, 20 and 15 strands,

1,430 yards length, 76 miles wire, 17 miles rented

Line E - Oxford Street, 30 strands, 660 yards

length, 16 miles wire, 4 miles rented

Line F – Pimlico, single wire, 7 miles, 6

miles rented

Line G - Victoria Docks, 30, 20 and 15

strands, 124 miles wire, 10 miles rented

Line H - Southwark ,30 and 19 strands, 13

miles wire, 3 ½ miles rented

Line J – Lambeth, a single wire, 6 miles,

2 ½ miles rented

Line K – Wapping, 30 strands, 59 miles

wire, 4 miles rented

This totalled 526 miles available in

London. It then had 412 miles of spare capacity in London, but 35½ miles had

applications from potential customers.

The District was also advertising heavily

and canvassing for subscribers in industrial Birmingham in the English Midlands

during December 1862.

Glasgow District 1862

Line A – 20 and 15 strands, 29 miles of

wire

Line B – 20 and 15 strands, 17 miles

Line C – 30, 20, 15 and 10 strands, 38

miles

Line D – 20 and 19 strands, 10 miles

Line E - Govan and Renfrew in progress

Line F – 20 and 15 strands, 14 miles

Line G – 30 and 15 strands, 69 miles

This totalled 177 miles of wire available in Glasgow.

In October 1862 the Universal company listed the following thirty firms as having private wires in Glasgow; Dalglish, Falconer & Co., calico printers, Glasgow to Campsie, Robert Napier & Sons, engineers and iron founders, Lancefield to Govan, Parkhead Forge Company, Vulcan Foundry of James Napier, Henry Monteith & Co., calico and silk printers, G & J Burns, ship-owners, Handysides & Henderson, ship-owners, William Sloan & Co., steamship agents, Charles Tennant & Co., manufacturing chemists, W & J Blackie & Co., printers and publishers, W & J Fleming & Co., linen works, A & A Galbraith, spinners and cloth manufacturers, David Hutcheson & Co., steamship agents, William Holmes & Brothers, shawl manufacturers, Murdoch & Doddrell, sugar refiners, Glasgow Iron Company, City & Suburban Gas Co., William Miller & Sons, turkey red dyers and calico printers, Strang & Hamilton, "twisters", Mitchell & Whytlaw, cloth manufacturers, Muir, Brown & Co., calico and silk printers, Robert Laidlaw & Son, ironmongers and iron merchants, Wylie & Lochhead, house furnishers, Edinburgh & Glasgow Railway Company, P & W McClellan, ironmongers and iron merchants, Greenock Foundry Company, J & A Allen's United States Steamship Office, George Miller & Co., manufacturing chemists and oil refiners, Bulloch, Lade & Co., spirit merchants, Lancefield Forge Company, among others.

It was to extend its lines in the autumn to the Vale of Leven, Barrhead, Thornliebank, Busby, Hurlet, Paisley, Greenock and Wemyss Bay. A plan was already in hand to link the Cumbrae, Pladda and Kintyre lighthouses to Glasgow city to provide information on shipping movements in the Clyde river.

Manchester District 1862

There were problems in developing the Manchester

business. On September 26, 1862 there were no multi-strand aerial cables in

use, but 20 miles were “suspended”, along with a single open wire.

A long report to the Board of Directors in August 1862 noted that Bonelli's Electric Telegraph Company and the Globe Telegraph Company were active in "tapping" its business. Their agent, Wheatley Kirk, had been dismissed but retained a stock of instruments and the books. Basil Holmes, the engineer's brother, was appointed Local Secretary in his place. In response to the competition Holmes, after negotiations with George Edward Preece, the Electric Telegraph Company's District Superintendent, proposed that extensions be immediately carried out using the Electric's rights-of-way on existing overhead pole lines at 1s a mile wayleave, and through rental of wires where they were already up on an annual payment. These would consist of circuits 1] Manchester to Liverpool (6 wires); 2] Liverpool to Northwich (3 wires); 3] Manchester to Warrington (2 wires); 4] Manchester to Patricroft (4 wires); 5] Manchester to Bolton (4 wires), and 6] Manchester to Ashton and Stalybridge (2 wires). He also wished to acquire rights-of-way from Manchester to Stockport, Bolton to Bury and Rochdale, and Rochdale to Oldham and Ashton. This would rapidly extend the Company's coverage of Manchester and Liverpool, which he felt could be quickly rented to private subscribers.

The remarkably competitive situation in Manchester was such that Holmes identified seven firms active in private telegraphy: Bonelli’s, W T Henley, Clyatt Morgan, Henry Wilde (the Globe Telegraph Company), John Faulkner & Company, Lundy Brothers and Wheatley Kirk & Company, their late agent. This came about, at least in part, through the policy of the Corporation of Manchester of freely granting permission for the carrying of open wires across and along public streets, which most local authorities refused.

Basil

Holmes left the Company’s service in Manchester after a couple of years

and returned to his previous profession of artist, painting landscapes

and sculpting, in Exeter, Devon. He was replaced by Frederick Evan

Evans, who proved more determined and subsequently joined the Post

Office Telegraphs.

The Company sought to lay its own cable across the Mersey connecting Liverpool and Birkenhead on November 7, 1861. The Docks and Harbour Board rejected the application.

The international mercantile cotton brokers of the port of Liverpool and the huge textile manufacturing industry based on cotton in Manchester were to prove some of the most enthusiastic adopters of private telegraphy. This was true even in the depths of the cotton famine brought on by the start of the latest internecine American war in 1861.

In March 1862 the Universal company proposed to erect a shipping telegraph between Cork and Queenstown in Ireland on the vital sea route to America, to report maritime traffic through a proposed new cable to South Wales and England. The Electric Telegraph Company invoked its agreement of September 1861 prohibiting any connection with other circuits. This dispute initially went to court but the suit was abandoned when the Electric bought out the cable company and agreed to the Universal's participation.On September 15, 1862 Reid Brothers agreed

to erect the “Coal Line” for the use of William Cory & Company, the coal

factors. It was a roadside circuit leading from North Woolwich, 14 miles to

Purfleet on the Thames estuary, to give early notice of colliers arriving in the

river. The long private line cost £364. Cory handled a million tons of coal a

year and was famous in the 1860s for the monster coal derrick, Atlas, moored on

the river for mechanically unloading the firm’s colliers.

S W Silver & Company had manufactured 534 yards of 60 strand cable, 416 yards of 50 strand, 8,079 yards of 30 strand, 8,769 yards of 20 strand, 5902 yards of 15 strand and 5,125 yards of 10 strand by the end of 1862.

It was not all business. The Company was

always ready to promote itself to the public in social events. A soirée

musicale, artistique et scientifique was held by the London Cambrian Society at

the London Coffee House, Ludgate Hill, on the evening of November 9, 1862. The

principal event was a concert with two fine singers and a harpist from the

Welsh community in London. Even so, as part of the scientifique element,

Professor Wheatstone was there with his Universal telegraph, which was personally

tried out by many of the visitors. He was not alone in the telegraph interest;

the Submarine and London District Telegraph companies laid on wires to connect

with their systems; Thomas Allen showed his “light cable” to span the oceans,

Cromwell Varley had his new “fault finder” on display, Owen Rowland, some cables,

Messrs Silver, some of their india rubber insulated wires, as did Messrs Hall

& Wells, and, on a lighter note, Francis Pulvermacher, the medical electrician,

demonstrated his batteries and other electrical apparatus, to “cure, without

pain, trouble, or any other medicine, all kinds of rheumatic, neuralgic, epileptic,

paralytic, & nervous complaints, indigestion, spasms & a host of

others.”

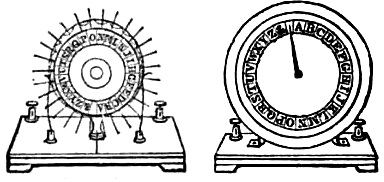

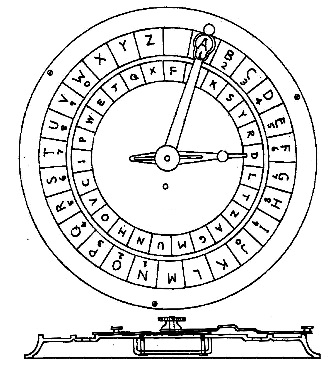

Wheatstone's Universal telegraph instrument of 1863

Now made much more compact and neater in a single mahogany case

There is a separate bell in this instance

Extension in 1863

On January 9, 1863 Reid Brothers completed the connection of private

wires between the head office of the London & Westminster Bank at

41 Lothbury, City, and its two major branches in London in the West End

at 1 St James’s Square, and in the “Borough” (Southwark) at 3

Wellington Street. David Salomons, chairman of the Universal Private

Telegraph Company, was also chairman of the London & Westminster

Bank.

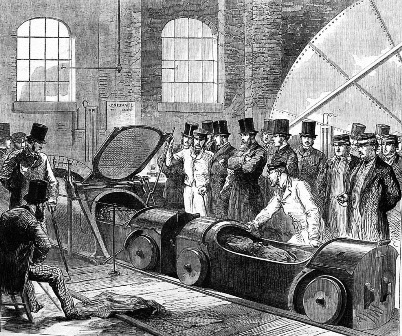

When the Pneumatic Despatch Company opened its underground tube railway between the arrivals platform at the Euston Square station and the North- Western District Post Office in Eversholt Street, London, during January 1863 Reid Brothers installed the Universal telegraph to signal the arrival and departure of its novel carriages loaded with letters and parcels. The Pneumatic Despatch was a development of the Electric Telegraph Company’s air circuits carrying messages between its offices in the City of London. Its cast-iron tubes were scaled up from 1½ inches in diameter to 30 inches, to contain close-fitting, four-wheeled railway waggons propelled by a vacuum. It was similar in operation to the “atmospheric” system worked on the London & Croydon and South Devon Railways, whose air pumps were controlled by Cooke & Wheatstone's newly- patented electric telegraph, 20 years previously, in the 1840s. The 580 yard long tube line opened for service on January 15, 1863 and worked thirteen miniature trains a day carrying mail for the Post Office.

The Pneumatic Despatch Company's 30 inch tube railway 1863

Moving mail bags from Euston Square railway station to a sorting office,

controlled by the Universal telegraph

Nathaniel Holmes presented a series of maps to the Board of

Directors in March 31, 1863 illustrating the aerial cables that the

Company had already erected in Manchester and Glasgow, and his future

plans:

• Manchester to Hyde, Stalybridge and Glossop

• Manchester to Oldham

• Manchester to Middleton, Bury, Haslingden, Accrington, Blackburn and Preston

• Bury to Wigan and Blackburn

Cables in the Manchester district were planned from Middleton to Rochdale and from Manchester to Stockport.

• Glasgow to Partick

• Glasgow to Campsie Junction and Kirkintilloch and Lennoxtown

• Glasgow to Leven

• Glasgow to Pollockshaws and Thornliebank with branches to Barrhead and Busby

• Thornliebank to Paisley, Port Glasgow and Greenock, to Paisley and Dalry

A long aerial cable was planned in the Glasgow district to connect with Edinburgh and Leith.

The five lines of aerial cable operating in the Manchester District during most of 1863 were designated:

Line A – PendleburyLine B – Halmer

Line C –

Line D – Oldham

Line E – Victoria Station

On December 8, 1863 the first subscribers and the first private wires were created in Belfast, Ulster, in Ireland. William Ewart & Son, flax spinners, linen manufacturers and bleachers, connected their office at 11 Donegall Place with their works at the Crumlin Road Mills; William Girdwood & Company, Old Park Print Works were joined to their offices at 16 Donegall Place; and Johnston & Carlisle, of Brookfield flax spinning mills in Crumlin Road had a line to 30 & 34 Donegall Street in Belfast city.

Virtual Office 1863

On May 1, 1863 the Universal

company announced in Glasgow that "The large Saloon on the ground

floor, 15 St Vincent Place, is to be fitted up into small counting

rooms for the accommodation of those firms in the suburbs and

neighbouring towns who have no offices in the city, and who may wish to

have private telegraph communication betwixt their works at a distance

and Glasgow. The premises are in close proximity to the Exchange. By

this arrangement a person whilst transacting business in the city can

consult or be consulted by those at the works as easily as if in the

next room. They will be let at £10 per annum."

An inclusive rate for telegraph and office was offered, an example of which was £34 per annum for a three mile line, inclusive of all maintenance. There was a "smaller rate per mile" for longer distances. As well as the City centre Pollockshaws, Barrhead, Hurlet, Nitshill, Paisley, Port Glasgow, Greenock, Springburn, Kirkintilloch, Campsie, Maryhill, Dalmuir, Kilpatrick, Bowling, Dumbarton, Dalreoch, Renton, Alexandria and Balloch were all then in private circuit.

Newcastle 1863

In January 1863, Basil Holmes in

Manchester began advertising for private wire clients in a new market:

Newcastle-upon-Tyne, the major centre for the coal-trade and for heavy

engineering in north-east England. This canvass was immediately

successful, leading to the establishment of a separate Newcastle

District office. In March 31, 1863 it planned three cables:

• Newcastle to Elswick and Scotswood

• Newcastle to St Anthony, Willington, North Shields and Tynemouth

• Newcastle to Gateshead, Friarsgoose, Jarrow and South Shields

In Newcastle the commonest aerial cable was one of seven "strands"; however a nineteen strand cable was run 440 yards across the river Tyne near Robert Stephenson's famous High Level Bridge.

In that District the earthenware insulators on its roadside open-wire circuits near colliery villages became a regular target for young vandals.

In January 1863 the Company began renting wires in Dundee through an agent, George Lowden of Union Street, in that Scottish city, initially to the Royal Exchange building.The board of directors, on June 12, 1863, anticipating substantial expansion and expenditure in the next few years, decided to increase its authorised capital. It would then amount to £190,000 in 7,600 ordinary shares of £25, all except £5 per share to be paid-up. The balance of 5,600 shares, not yet with the public, was then offered for sale. Not all of this was taken up, but it did cause a considerable change in shareholding, with provincial participants overtaking London capitalists.

The Universal company was able throughout its life to avoid the use of preference shares and the need for any loan or debenture issues, such was its strength in the capital markets.Mr Holmes' Artillery

One day, a coalminer from some distant part of Durham, who had never heard of such things as time-guns, was passing across Newcastle Bridge, when he was startled by the sudden roar of the gun just above him. Amazed, he asked a passenger "what that was," who replied that it was "one o'clock." "One o'clock!" exclaimed the miner; "I'm very glad I were not here at twelve."

Mechanics' Magazine 1864

Time Guns

In Newcastle, from August 17, 1863, the

Universal Private Telegraph Company, at the instance of Nathaniel

Holmes, took a time-signal from Royal Observatory, Edinburgh in

Scotland, off the Magnetic Telegraph Company's circuits and used

Wheatstone's magnetic exploders, rather than galvanic batteries, in its

office at one o'clock each day to ignite the charges of "time-guns" at

the Old Castle in the city and at Barrack Hill several miles away in

North Shields, signalling the precise hour of the day as a public

service.

The process was described in 1865: "Mr N J Holmes... arranged a time-gun at Newcastle, 120 miles distant [from Edinburgh], to be fired by means of Wheatstone's magneto-exploder and Abel's magneto fuse; and on a fair day the current sent off along the telegraph wire discharged the gun with no sensible hesitation or 'hang fire;' but on a foggy day the highly intense magneto current was in too great a degree dissipated and lost. A practical system was finally devised, by causing a large signal-sending clock to discharge along the line of telegraph wire, at the due moment, a galvanic current of low intensity; this, on reaching Newcastle, was made to liberate in the proper apparatus there the more intense magnetic current, which had then only a few hundred yards to travel to the gun."

The Edinburgh Electric Time-Gun 1861

In August 1863 it was improved by Nathaniel Holmes, dispensing with

the local clock shown here and made to work remotely over 120

miles distant from the Edinburgh Observatory in Newcastle-upon-Tyne

The Company provided three more time-guns in Scotland: at St Vincent Place, Glasgow on October 29, at Broomielaw, Glasgow on November 10, and at Greenock on the Clyde on November 21, 1863. However all of these were abandoned in November 1864 at the insistence of the Electric Telegraph Company who objected to the use of the Magnetic's circuits, and who wanted to install its own time-balls regulated from Greenwich.

Not all Glaswegians appreciated the time-gun. Nathaniel Holmes was summonsed at the Police Court on a charge of discharging a cannon from the roof of No 15 Vincent Square to the inconvenience or danger of passers-by on November 16, 1863. Holmes' defence was that proper notice had been given. He also pointed out that, two years previously, when the first time-gun had been commenced in Edinburgh all the complaints came from a single individual who adopted a multiplicity of names in writing to the Police there. The justices dismissed the summons.A temporary time-gun was set up by the Company in the yard of the Orphan Asylum in Sunderland on August 26, 1863 to fire off at one o'clock each day in celebration of the annual meeting of the British Association for the Advancement of Science in that city. The reaction of the orphans is not recorded.

The Company established a time-gun at the entrance to the basin in Dundee harbour in Scotland on December 23, 1863 for a short period.

By December 1863, it had, or anticipated, working remote electric time-guns at Aberdeen, Dundee, Glasgow, Birmingham, Coventry, Hull, Dover and Tilbury, as well as those in Newcastle and North Shields.Its last time-gun was introduced in Belfast in Ireland at the invitation of the Chamber of Commerce in 1865. It, too, was connected by a circuit to Edinburgh Observatory and was installed by the Company at the Harbour Office. The gun fired daily at 1 o'clock Greenwich time as part of the Chamber's campaign to have time uniformity with Britain.