13. THE COMPANIES ABROAD

The

acceleration in communication brought about by the electric telegraph

is most vividly illustrated in the links with territories abroad,

especially when divided by oceans. Britain was a commercial nation,

built upon trade; its interests in the nineteenth century were

world-wide. But even in 1852, when steam and iron had been long applied

to create regular lines of ocean navigation the time-scales for

communication were immense. A letter from London took 12 days to reach

New York in the United States; 13 days to Alexandria in Egypt; 19 days

to Constantinople in Ottoman Turkey; 33 days to Bombay in India; 44

days to Calcutta in Bengal; 45 days to Singapore; 57 days to Shanghai

in China; and 73 days to Sydney in Australia. From this state of

affairs, within twenty years, the telegraph companies created links

that allowed messages to be sent to all of these places inminutes.

As with most other matters connected with their operation the telegraph companies were secretive in regard to foreign traffic: between 1851 and 1866 this essentially meant communication to the continent of Europe by way of the English Channel and the German Bight.

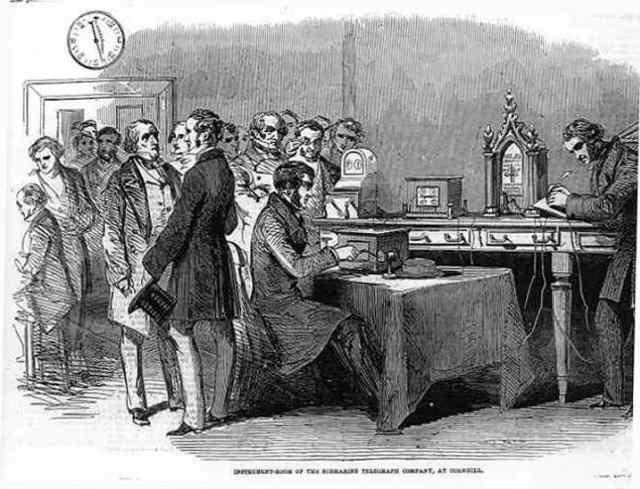

The

first message is received by the Submarine Telegraph Company in London

from Paris on the Foy-Breguet instrument in 1851

Cooke & Wheatstone's one and two-needle telegraphs are ready for use in the background

Europe

Outside of

Britain telegraphy was the first technology to have successful

international regulation, as the necessity for cross-border interchange

of message traffic was obviously essential.

The first such international regulatory body was the Deutsch-Oesterreichischen Telegraphenverein, the German-Austrian Telegraph Union, which was created by the Treaty of Dresden on July 25, 1850, allowing direct circuits between Austria, Prussia, Bavaria and Saxony.

Throughout Continental Europe electric telegraphy was a monopoly of the state, several of which states, France and Austria being notable, only grudgingly permitting any public access for messages. This situation ostensibly allowed uniform regulation and agreement. However, in true European fashion, two conventions were convened to regulate international telegraphy. The first convention was based on an expansion of the original German-Austrian Telegraph Union, and was signed in Berlin on June 29, 1855 encompassing Austria, Prussia, Holland, the German Confederation (i.e. the smaller German states), Russia, Turkey and the Italian States (except Sardinia). The second was signed in Paris on December 29, 1855 between France, Belgium, Spain, Sardinia and Switzerland. The two conventions adopted differing zone tariffs for out-going, revenue-generating messages. The American telegraph was the sole instrument used, recognised by both agreements.

In addition to these conventions the German-Austrian Telegraph Union negotiated access agreements with France and Belgium (October 1852 and again in June 1855) and with Switzerland (October 1858). Britain, Denmark, Norway and Sweden were not party to either of the telegraph conventions but despite this were in connection through bi-lateral treaties with one or other of the signatories.

The conventions affected Britain in that:

• The traffic of the two Submarine Telegraph Companies (one having monopoly rights to France, the other having rights to Belgium) was primarily regulated by the Paris Convention. Between 1859 and 1865 it also was to have cables landing in Hanover in Germany and Denmark.

• The messages of the Electric Telegraph Company, whose cables landed in Holland and Hanover, were regulated by the Berlin Convention.

In Britain these continental connections were known as 'German' via The Hague, 'Belgian' via Ostend, and 'French' via Dover. Whichever company the sender used in Britain they, ostensibly, had the option of specifying the route based on printed tables held at the telegraph offices. The criteria could be expense - the 'German' route was invariably cheaper, or speed - the 'Belgian' route was more direct and so could actually be quicker into the German states, and the 'French' quicker than the 'Belgian' to Southern Europe.

Regarding the market in Great Britain, the European Telegraph Company's limited number of domestic offices offered access to the Continent from November 1852 via Calais and Ostend. The European company was a satellite promotion of the Submarine Telegraph Company. To these connections were added those of the British company in the north of the country in September 1854. In 1857 these inland circuits, linked to the Submarine's, were united with those of the English & Irish Magnetic company. The original Electric Telegraph Company's much larger range of domestic circuits were connected to Europe from May 1853 via The Hague in Holland. The Submarine Telegraph Company maintained offices for messages in Paris, Brussels and Antwerp before the common adoption of the American telegraph on its and on all of the Continental circuits in 1855. Similarly, the Electric & International Telegraph Company had offices in The Hague and Amsterdam, before handing traffic over to the Rijkstelegraaf in Holland in 1859. It also maintained third-party telegraph agents in Berlin, Vienna, Hamburg and Trieste for the convenience of foreign merchants and others trading with Britain.

For a period, in the mid-1850s, people like Reuter became 'consultants' to mercantile houses in London in managing the complexities of foreign telegraph traffic. In 1853 he, after being the sole agent for the Submarine Telegraph Company in London, received a 7% discount for directing such messages exclusively through the circuits of the International Telegraph Company, the Electric's cable-operating subsidiary.

The dominant Electric Telegraph Company would generally refuse traffic designated for the 'French' route, giving preference to its own Dutch cables. Only the Magnetic, through the Submarine company's French, Belgian, Hanoverian and Danish cables, had a choice, albeit a short-lived one, of all three connections. So as far as telegraphy from Britain was concerned the Electric company sent and received the majority of messages for Holland, Germany, Scandinavia, Russia and Turkey, whilst the Submarine company served France, Belgium, Spain, Portugal and Italy, through to Egypt. However both companies could send messages addressed to any connected country, relying on its continental associates to retransmit them appropriately.Deutsch-Österreichischen Telegraphenverein

The German-Austrian Telegraph Union was the

Electric Telegraph Company's great ally in Europe

Union Stations in Europe 1862

Austria.....................................239

Prussia.....................................197

Bavaria.....................................49

Saxony......................................26

Hanover....................................36

Württemberg.............................65

Baden........................................65

Mecklenburg.............................15

Netherlands..............................63

Total.........................................755

There were other, local, stations in these countries; the Union managed 4,494.9 'geographical miles' of line and 9,633.2 'geographical miles' of wire in 1862. The geographical or nautical mile equals1 minute of arc along the Earth's equator, or 6,080 feet.

Statistics from 'Encyklopädie der Physik' XX Band, 1865

The Electric company quickly established good relations within the 'German' sphere, for example when the German-Austrian Telegraph Union amended its rates on November 12, 1855 these were extended to Britain so that messages to Austria, Prussia, Saxony, Bavaria, Wurttemberg, Hanover, Holland and Russia were allowed five words for the address free-of-charge and pre-paid answers up to ten words at half-rate. By 1855 it had an indirect circuit through to Constantinople in Ottoman Turkey. This utilised a line erected by French contractors for the Ottoman government, in support of the Crimean campaign, between Semlin on the Austrian border, to Sofia, Adrianople and the Turkish capital A direct line was opened to public traffic on May 2, 1858. Political problems between Austria and Sardinia and between the Italian states prevented extension into Italy. The Magnetic and the Submarine companies only reached Rome and Naples in 1855 through French influence, and required the laying of an Adriatic cable to the Balkans to reach Constantinople in 1859.

Effective from January 1, 1866 an agreement made at an International Telegraph Conference in Paris during the previous year united the working of twenty-one state systems in Europe. Britain, with the largest telegraphic traffic and just about to create the circuit to the Americas, was excluded from this convention.

The late-coming United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company obtained access to the Continent in 1868 by way of the Great Northern Telegraph Company of Copenhagen, through Denmark.

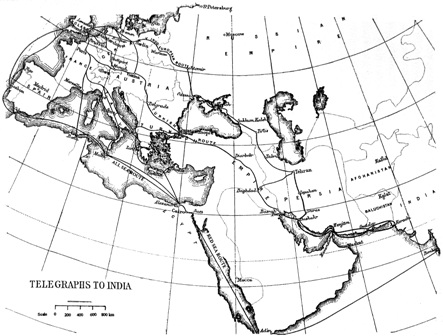

India and the Far East

For

Britain by far the most important foreign connection was that to its

territories in the Far East. By 1868 the electric telegraph had reached

out to Rangoon and Moulmein in Burmah; and the major Indian cities of

Calcutta and Bombay had been in regular if slow and somewhat unreliable

communication with London since January 27, 1865.

Although Britain was not involved in them the 1860s saw a series of conflicts in Europe that disrupted the technological advance of telegraphy to the East.

The Italian Wars of Unification commenced in 1859 when the French Empire in support of Kingdom of Sardinia (which included Piedmont (Turin)) expelled the Austrians from Lombardy (Milan), in return seizing Savoy and Nice. In 1860 and 1861 a military expedition united the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies (Naples and Sicily), the Duchies of Tuscany, Parma and Modena, and the Papal States of Umbria, the Marches and Romagna with Sardinia to form the Kingdom of Italy. Through the military support of Prussia the new Italian state acquired Venetia from Austria in 1866. Finally Rome was incorporated into Italy in 1871 with the withdrawal of the French Imperial protectorate that had existed since 1848. Italy was a battleground for most of the decade.

The French ensured that the absorbed Italian states abandoned the German-Austrian Telegraph Union for the Paris Convention on telegraphy in 1862, and messages from Britain for Rome, Naples, Malta and Alexandria thenall passed through the Submarine Telegraph Company's circuits, hence by way of Savoy.

Central Europe was also a battleground. There was a bitterly fought uprising in the Russian General-Government of Warsaw in 1863. Prussia and Denmark fought over Schleswig-Holstein in 1864, the former being the victor. This was followed by a war between Prussia and Austria and their allies in 1866 which culminated in the absorption by Prussia of the smaller German states in North Germany, including the former British viceroyalty of Hanover.

The East India Company's Telegraph - Until 1858 the East India Company managed political, financial and military matters in the Indian peninsular, Ceylon, Burmah and Pegu on behalf of the British government and the Indian principalities. William O'Shaughnessy, a doctor in its service, according to his own account, had been experimenting with electric telegraphy since 1837 and, independently of European and American experience, developed his own system for use in India by the late 1840s. O'Shaughnessy was given permission by the Bengal Presidency of the Company in 1851 to construct, as "a national experiment", a line of electric telegraph from Calcutta to Kedgeree, a distance of 80 miles, by way of stations at Bishtapore, Atcheepore and Diamond Harbour. It was opened for government and company service, and for the use of subscribers in the shipping and mercantile communities, on October 6, 1851.

In this trial he successfully used circuits of iron rods and simple, locally- developed electrical technology, using current reversers and galvanometers.

The Governor-General of India, Lord Dalhousie, was sufficiently impressed by O'Shaughnessy to have the East India Company extend his system from Calcutta to Agra, from Agra to Bombay, Agra to Peshawar, and Bombay to Madras; linking the Company's three administrative departments or Presidencies, Bombay, Madras and Bengal. By November 1853 the East India Company had expended £110,000 on telegraphy, adding Simlah and Lahore to its circuits, totalling 3,150 miles of line for its private use.

Dalhousie also had O'Shaughnessy sent to London in 1852 to present to the Court of Directors of the East India Company his ideas on electric telegraphy. The Court, however, had already taken the subject into consideration and had commissioned a report of the engineer Francis Whishaw. Whishaw recommended and they initially accepted the use of underground circuits of copper wire insulated with gutta-percha and buried in wooden sleepers treated with arsenic to prevent attack by insects. The Court however, endorsing Lord Dalhousie's recommendation, appointed O'Shaughnessy the Superintendent of Telegraphs for India with full powers over technical matters.

Once in England O'Shaughnessy thoroughly researched the current progress of telegraphy. Commencing in May 1852 the East India Company began an elaborate series of test and trials at its military depot at Warley, near Brentwood in Essex. O'Shaughnessy had between three and four thousand yards of iron wire erected on posts, training the Company's sappers and miners in telegraph construction. He intended to have poles in India fourteen feet high and a furlong (one-eighth of a mile) apart, with especially thick iron wire. The poles were to be fixed with iron screw-piles. For underground circuits he had the sappers and miners lay ten thousand yards of copper wire insulated in gutta-percha resin in wooden sleepers treated, as Francis Whishaw recommended, with arsenic to make them proof against ants.

On October 5, 1852 the chairman, Sir James Hogg, and members of the Court of Directors arrived by Special Train on the Eastern Counties Railway at Brentwood to review O'Shaughnessy's activities, proceeding to Warley with an escort of cavalry. They were then to make a decision on laying 3,000 miles of telegraph circuits in India by their own army. Stores were being assembled at Warley for shipment anticipating commencement of construction in January 1853.

East India Company Telegraph, outside Madras 1854

Very simple, single wire circuits, similar to American practice

The actual instruments to be used had yet to be decided. The patentees of several telegraph systems were present on October 5 to demonstrate their systems: Thomas Allan, Alexander Bain, Frederick Bakewell and Jacob Brett all attended the Company's directors on Warley Common. The "show" was stolen by Samuel Statham of the Gutta-Percha Company who used his novel fuse to detonate explosives electrically over long distances. O'Shaughnessy, after an exhaustive review of all available telegraphs, decided to abandon his own indigenous telegraph system substituting that used in the United States which better reflected conditions in India, selecting the rough and ready American telegraph, with its simple key and clockwork register.

To complete the events of October 5, 1852, after a late afternoon "cold collation" Sir James Hogg, O'Shaughnessy and the Court thanked their soldiers for all their efforts and returned to London on the Special Train.

The East India Company's improved telegraph was opened for public messages on February 1, 1855. In preparation for this a school for European telegraphers was opened at Gresham House, Old Broad Street, London, to familiarise them with the American telegraph. The initial intake was 40 trainees; this was raised almost immediately to 72. By the following year there were 4,250 miles of line, with 46 stations.In pursuit of simplicity the Company adopted subsequently the American acoustic receiver or “sounder”. Shaughnessy opened instrument workshops, under Mr Faulkner, to manufacture American sounders for use on Indian circuits, at one-tenth of the cost of Siemens & Halske’s finest recording instruments with their complex clock-work. The site he chose for this new technology in 1857 was Bangalore, where the successors of this enterprise flourish to an immense degree today.

The East India Company was dissolved in 1858 at the end of the mutiny of elements of its military force and India became a British viceroyalty. The British India government appointed William O'Shaughnessy to be Director-General of Telegraphs. His system was further expanded to 10,994 miles of line with 136 stations by 1859, in which year 170,566 public messages were sent.

Unfortunately by May 1861 the administration of the India telegraphs fell into the hands of a superannuated army officer, Major C Douglas, who proved to be a master of self-serving inertia. Worse still, he appointed other ill-equipped army officers to district superintendencies, neglecting the welfare of the Indian employees and gradually undoing the economies and efficiency of O'Shaughnessy's telegraph system. It was not until July 1865 that the India government managed to dismiss Douglas for his continued incompetence.

In

June 1861 the Chambers of Commerce in India reported that 8% of its

members' telegraph messages were "unintelligible, contained important

errors or so delayed as to be useless".

Trust in the India Government Telegraphs

was depleted further in early 1861 when two former clerks, George Pecktall and

William Allen were engaged by opium speculators in Bombay to interfere with messages

from China affecting the trade. According to the ‘Bombay Gazette’ of February

27, 1861, “enormous sums of money” were made from their activities.

The telegraph wire from Galle, where the

China mail steamers touched to deposit commercial messages regarding the opium

business, passed through Sattara and Poona on the way to Bombay. The miscreants

cut the wire four miles out of Poona and inserted a railway telegraph and a battery,

reading the incoming messages, which they sent by post their sponsors in Bombay,

before changing and re-transmitting them to suit their speculative interests.

Foolishly they failed to restore the circuit when they ceased their operation;

the line break was investigated and the fraud discovered.

By 1863 the Indian telegraphs had 14,500 miles of line, reaching as far east as Rangoon in Burmah. But its services under government control had become slow and unreliable, with a large and highly paid European bureaucracy overseeing a demoralised Indian staff.

During 1863 the Electric & International Telegraph Company in England projected the Oriental Telegraph Company to construct 4,000 miles of public line sharing those circuits already built along the Indian railways for their own service, and successfully united the railway companies in its support. But the government in London forbad this competition to its monopoly in September 1864.

Overland to India - Each domestic telegraph company contracted for its own circuit through the foreign state-owned wires to the east. However competition initially only ran to Constantinople, the capital of Ottoman Turkey, where the British had laid an underwater cable to cross the Bosphorus from Europe to Asia in 1856.

The Electric's primary eastern circuit, the oldest dating from the circuits erected in 1855 for the Crimean war, went from London to the Hague, to Berlin or Frankfurt, Vienna, Belgrade (then in Turkey) on to Constantinople. Transcription of messages took place at either Berlin or Frankfurt, and again at Vienna and Belgrade.

The principal eastern route of the Magnetic company was created in 1859 and extended from London to Paris, Turin, down the east coast of Italy, across the Adriatic Sea by submarine cable from Otranto to Valona (then an Ottoman city) hence to Salonika and to Constantinople. Messages were transcribed at Paris, Turin, and Otranto or Valona before reaching the Turkish capital. The Imperial French authorities, it was claimed, "inspected" foreign through-traffic on this circuit, even diplomatic messages.

By 1859 the Electric had two alternate circuits available through to Ottoman Turkey: the so-called Austrian route, by way of Vienna, Pressburg, Pesth, Szolnok, Debrezin, Klausenberg, Karlsberg, Hermanstadt, Kronstadt, Bukarest, Rustchuk, Giurgiovo, Shumla and Lule to Constantinople. The alternative was the Serbian, its original route, also from Vienna but by way of Agram, Peterwardein, Belgrade, Nissa, Sophia, Phillipopolis, Adrianople and Lule to Constantinople.

The Electric Telegraph Company contracted with the Netherlands government, who were members of the German-Austrian Telegraph Union. The Company claimed to have no direct dealings with the Union or systems that the Union connected with. It reconciled its foreign message account every three months with, and passed on complaints from customers to, the Dutch. The Union similarly settled the message accounts with its connections and relayed on the complaints. Accounts were generally well-kept but complaints were rarely responded to, and where the cost of the message was reimbursed by the Company it was without much hope of recovery. It was sending messages from London to Vienna and Constantinople through Frankfurt, by preference to the circuit from Berlin to Vienna as Union traffic between the two capitals was intense and foreign messages were low in priority. The need for manual transcription had been eliminated by 1865 and the Company could telegraph Constantinople directly, but only at night when Continental domestic traffic was limited. For this reason, too, the Union commonly held the Company's traffic for manual transcription at Frankfurt and Berlin, giving preference during the day to its own messages.

An Indo-Ottoman Telegraph Convention between Britain and Turkey in 1860 was to secure an exclusive overland circuit from the Austrian-Ottoman border to Basrah in Turkish Arabia. It was planned to comprise a land line from Constantinople to Scutari, Izmid, Angara, Sivai, Diarbekir, Mosul, Baghdad and Basrah on the Gulf, as a roadside overhead or pole line from Scutari to Baghdad, and a novel "subfluvial" (river-bottom) cable hence down the river Tigris to Basrah and Fao where it would connect with an ocean cable to India. As with other government telegraph works the Convention lines were prolonged in their completion; they took five years to be fully implemented.

The initial stage proceeded relatively quickly. British engineers supervised the construction of the overhead line from Constantinople to Baghdad and this was opened on June 10, 1861.

The subfluvial cable from Baghdad to Basrah was, after much dispute with the Ottoman authorities, substituted by an overhead circuit as the British government's engineers claimed that the river-bottom cable would cost twelve times as much as wires on poles.

The Convention line eventually opened throughout in January 1865, for Indian traffic through from Constantinople to Baghdad in Mesopotamia and to Fao at the head of the Persian Gulf, where the British-India government underwater cables to Kurrachee had landed in 1864. The Indo-Ottoman line ran nearly 2,000 miles on poles, and used Greek or Armenian operators. It was financed in great part by a grant from the British India government as part of the convention.

The British India government cable extended in sections 300 miles from Kurrachee to Gwadur, then 400 miles to Musandam, 400 miles to Bushire and finally 150 miles to Fao. W T Henley's Telegraph Works Company contracted for the cable-making and laying in December 1862. The works were completed west from Gwadur to Fao on April 8, 1864 and east to Kurrachee on May 14, 1864.

The short cable between Europe and Asia had been repaired three times since its construction in 1856, but was finally abandoned in 1860 - message traffic across the Bosphorus then being carried out by steamer. Then, as part of the Convention, two short underwater cables dedicated to Indian traffic were added with two more beneath the Bosphorus for Ottoman use.

On March 1, 1865 the Submarine Telegraph Company and the British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company, in contractual alliance, offered message rates from their offices in Britain via Constantinople to the principal cities of India, Burmah and Ceylon.In the east the British-India Government created the Indo-European Telegraph Department in 1863 to build a line across Southern Persia from Khanaquin on the Ottoman border to Bushire where its cables were to land and in 1868 to build a land line from Bushire to Gwadur and Kurrachee in India.

The service through the Ottoman Turkish territories was terrible, with long delays and garbling of text; an alternative through Russia's governmental wires became equally execrable when entering Persian state circuits, as both involved operators transcribing unfamiliar languages and foreign scripts. The "circuit" from London to Calcutta was opened on January 27, 1865; but only once in 1866 did a message get through in under twenty-four hours, they regularly took several days to transit the government wires in Europe and Asia.

The Electric had on average 30 messages a day for India and received a maximum of 175 during 1865, after the first land circuit to Calcutta opened, before the submarine lines were created. The speediest message from India was received in 1 hour 50 minutes, but most took between a day-and-a-half and nine days, allowing for a five hour time difference between London and India.Similarly the Submarine company, by its concessions, dealt with the French and Belgian governments, but not the networks with which they were conjoined. In 1863 it was sending messages to Constantinople by way of Paris, Munich and Vienna, or by Paris, Turin, Otranto Valona and Belgrade. The choice was made by the French authorities. If the message was sent through Brussels it was forwarded by way of Berlin and Belgrade. Two-thirds of its messages were then by way Paris and one-third through Brussels. The longest transmission time to India in 1865 was 17 days, the shortest 17 hours. The average transit time for the 20 or so messages for India that the Submarine company transmitted daily was 48 hours.

In 1865 the Electric company was handling 67% of outbound and 98% of inbound traffic from the Far East; the Submarine company had 29% of outbound and 2% of inbound messages. The source of 4% of outbound messages was not known. In parenthesis, it can be added that the statistical situation was reversed for messages through southern Europe, where the Paris convention ruled; the Submarine company dominating to Spain, Portugal, Italy and Egypt. However, errors and delays caused the Submarine's chairman to declare in 1866 that "We would much sooner not have Spanish and Portuguese messages at all."

From 1864 the British Government looked to sponsor much more secure and reliable communications with India and Australia, by other land-lines and, eventually, by a series of wholly British-owned and operated ocean cables.

This need was brought home by the disruption of telegraph traffic to both Constantinople and Alexandria in the ‘Seven Weeks War” between Prussia and its allies, including Italy, and Austria and its allies in the summer of 1866. No messages could be sent through Germany or Italy whilst hostilities lasted, around two months.The Electric Telegraph Company and Siemens & Halske projected the Indo-European Telegraph Company in 1867 to overcome these problems. It was to be a land route through the Prussia, Russia and Persia, where its continental promoters, Siemens & Halske, had strong influence. It was completed from London to join with the cables to India in the Persian Gulf in 1870, using the English language throughout. Its history can be found under the chapter 'Competitors & Allies'.

Although its capital was mainly English, provided by the directors of the Electric, the Indo-European Telegraph Company was essentially a German concern. In the later part of the nineteenth century it was regarded by the British Government as being protected by Russia in Persia, so untrustworthy for official messages.

Distant Australia was served in the late 1860s by sending telegraph messages from London to Galle in Ceylon where they were taken by mail-boat to Adelaide in South Australia.

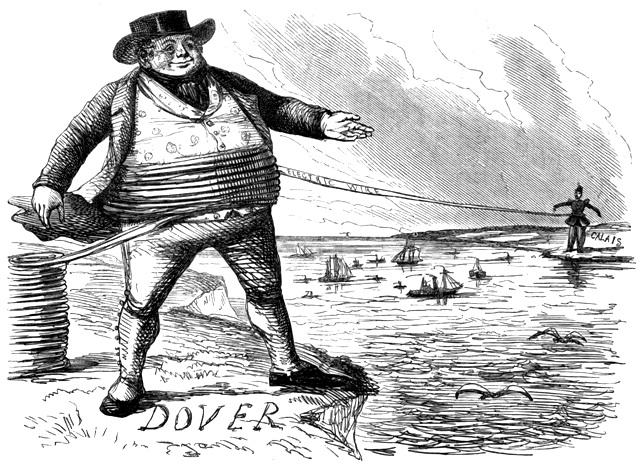

Siamese Twins 1851

Punch celebrates the joining of England and France by submarine telegraph on September 25, 1851

The first toe-in-the-water towards uniting the continents

Underwater to India – There were to be several lines of approach by British companies to link London with the cities of India by submarine cables. This divided into two elements, west of Alexandria in Egypt to Europe and east of Alexandria to India. It was to be chaos; with the governments of Britain, France, Austria, Sardinia, Turkey and Egypt, not to mention the Court of the East India Company, intervening. A telegraph to India was, however, to be ultimately successful with a long series of underwater cables, scarcely touching foreign territory only after 1870 solely through the efforts of British public companies.

The first difficulty to overcome was the crossing of the Mediterranean Sea: there were three routes planned to Alexandria on the route to India; from southern France; from Constantinople; and from Austria – with several variations, branches and diversions.

In 1854 John Watkins Brett projected the Société du télégraphe électrique Méditerranéen, known better as the "Mediterranean Electric Telegraph", incorporated under French law, simultaneously in Paris, Turin, capital of the Kingdom of Sardinia; and London, England; to connect France, Corsica, Sardinia and the major French colony of Algeria by underwater cables. As with the cable of 1851 across the Channel the ownership of the new concession was vested in the Société Carmichael et Compagnie, a private partnership. The construction and operation was let to the separately organised Mediterranean Electric Telegraph with a capital of £300,000 on which 4% was guaranteed by France on £180,000 and 5% by Sardinia on £120,000 for fifty years. The connection was a six-core cable from Spezia to Corsica (75 miles), land lines across Corsica (128 miles), from there to Sardinia by cable (10 miles), and across that island (200 miles). There was to be a 125 mile deep-water cable from Sardinia to Secali in Africa. These were to be made by Glass, Elliot & Company of London, their first large project. An underground circuit was to lead west to Algiers for French traffic and another east to Alexandria in Egypt for British messages to India. It was intended to imitate Brett's Submarine company, the only other foreign telegraphic concession granted by the French Empire, but it did not repeat that success. The Africa cable failed over several attempts and the Société Carmichael et Cie abandoned its landing rights to the French government in 1856; the operating Company itself became entirely Frenchas the Société du télégraphe électrique sous-marin de la Méditerranée, surviving until early February 1867, when it was finally declared bankrupt.

The Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company was then promoted by John Watkins Brett in London to serve British interests in the extreme south and east of Europe during August 1855. In 1857 it had a capital of £120,000 in twelve thousand shares of £100 and was intended to connect Alexandria in Ottoman Egypt with Europe, by way of Malta, the Royal Navy's chief station in the Mediterranean, for which it was to receive a guarantee of interest of 6% from the British government. However it ended up connecting Cagliari in Sardinia, where the original concession terminated, with the islands of Malta and Corfu, with two cables made by R S Newall & Company. The latter island was then a British possession, part of its protectorate of the Ionian Islands off the Greek coast. When the original Mediterranean concession was surrendered, the Extension company added a 70 mile cable, made by Glass, Elliot & Company, from Malta to Sicily, hence to mainland Italy and the state circuits in Europe, in September 1859. It also had Glass, Elliot lay a cable, its fourth, from Corfu to Otranto in southern Italy in 1861.

The Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company eventually possessed an office in London, a central station at 27 Strada Stretta, Valetta, Malta, and stations at Corfu, Naples, Cagliari and Turin. In 1858 it had a tariff of 10s 6d for twenty words between Cagliari and Malta and Malta and Corfu when it managed 7,512 messages.

At the eastern end of the Mediterranean, on May 14, 1855 Lionel Gisborne negotiated a 50 year concession of the Ottoman Turkish government for a cable connecting Constantinople and Alexandria in Egypt. The Ottoman government was to pay an annual subsidy of £4,500 for twenty years, and receive in return free message rights for four hours in every twenty-four.

To work this Gisborne formed the "Eastern Telegraph Company" on September 25, 1855 to make the cable from the Dardanelles, for Constantinople, to Alexandria, with a monopoly of landing rights for cables to Alexandria from any place in the Turkish dominions. The raising of capital for this was difficult and the company was nearly abandoned in November 1855. However Gisborne negotiated a further concession on February 28, 1856 of the Pasha of Egypt for the company to make a telegraph in his territories between Alexandria, Suez and Kossier, and Kossier and Aden on the Indian Ocean, with a dedicated circuit for Indian traffic. There would be no Egyptian subsidy but all public messages would have to use the state telegraph offices. Even this enlarged concession failed to attract capital, although Gisborne retained the rights.The company had to be reconstructed and a new concern, the Levant Submarine Telegraph Company, was created in London by Lionel Gisborne and R S Newall, the cable manufacturer. It obtained a new fifty-five year concession of the Ottoman Turkish government on January 10, 1857 to connect the capital Constantinople with its territories of Crete, Palestine and Egypt.

During June 1858 Newall laid 600 miles of underwater cable based on a hub on Scio (Chios). This Aegean island was connected by cable to the Dardanelles, where there was a land line to Constantinople; to Candia on the then-Turkish island of Crete; and to Smyrna, the main commercial city on the Ottoman Anatolian coast. Two further cables, made by Newall for the Greek government in June 1859, linked Scio to the Aegean island of Syrah, then the chief port for Greece, and from Syrah to Athens, the Greek capital. The principal office continued to be on Scio, with a director and six clerks, handling considerable traffic from Trieste in Austria through Athens to Smyrna and Constantinople. Adolf Buffleb, a former employee of Siemens & Halske, was the Levant company's General Manager and Electrician on Scio in the mid-1860s.

The Levant company planned, but failed after three attempts, to make a long cable from Candia to Alexandria, the port of the Ottoman Pashlic of Egypt, on the way to the Red Sea and India. It also planned, but failed to make, a cable from Candia to Jaffa in Palestine. In these R S Newall, then in financial difficulties after underwriting the costs of both the Levant and Red Sea cables, substituted a cheaper hemp and tar outer covering for the iron wire armour originally specified.

Six years later the Levant company, without Newall's help, contracted with the British government to lay a series of short cables, 74 miles in total length, between the Ionian islands of Corfu, Santa Maura, Ithaca, Zante and Cephalonia; to join at Corfu with the Extension company's cable.

During 1857 John Watkins Brett was in Vienna. On September 17, 1857 he announced that he had contracted with the Imperial & Royal Austrian government to build a cable from Ragusa on the Adriatic coast to Alexandria. In return he would receive £500,000 – two-thirds in cash for construction and one-third in shares of the Austrian Submarine Telegraph Company that was to be formed to work the circuits. The Austrian government would own the three-core cable but the company would have a 50 year concession to work it with the American telegraph for a guarantee of interest of 6% on its capital for twenty-five years. Official British and East India Company messages were to have priority before those of the Austrian, Ottoman and Egyptian governments; for which privilege the Treasury in London paid half of the guarantee of interest.The actual line was intended to run from the port of Cattaro to Ragusa, Corfu, Zante, Candia and Alexandria in Egypt with a branch to Seleucia in Palestine. However the Ottoman authorities were not disposed to grant landing rights to Alexandria without a collateral cable connection with Constantinople; as agreed in Gisborne's original concession.

All this left the British Government ostensibly with three choices through the Mediterranean to connect with India - 1) the Austrian route from Ragusa to Alexandria (which had a branch added to Constantinople at Ottoman insistence); 2) Gisborne's route from Constantinople by way of Candia to Alexandria; and 3) Brett's route from Cagliari through Corfu to Alexandria. To add to this choice the Kingdom of Sardinia had already proposed on June 16, 1855, in return for a British subsidy, to make the cable from Cagliari to Malta and Alexandria. Gaetano Bonelli, the Sardinian director of telegraphs, repeated the offer on February 18, 1858.

Not being satisfied with this already confused state of affairs in 1859 the British Government also sought tenders for a direct Malta to Alexandria three-core cable from the Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company and from R S Newall & Company. Brett quoted between £440,000 and £450,000 with a 4½ % annual guarantee of interest. Newall refused to quote for a direct circuit but suggested a coastal cable joining the towns along North Africa for £460,000 with a new connecting wire from Malta to Cagliari for £65,000. The cost to the Government for these would be over £20,000 a year in guarantees, compared with £15,000 a year for the Austrian route.

Not one of these government-sponsored lines was completed through to Alexandria!

East of Alexandria, guided by William O'Shaughnessy, its Superintendent of Telegraphs, the East India Company had already planned to build its own cable from Kurrachee in India to Bussorah or Kornah in Ottoman Turkey at the head of the Persian Gulf; a further riverine cable laid safely in the bed on the Tigris up to Baghdad; and a land line from Baghdad to Aleppo and Seleucia or Scutari on the Mediterranean Sea. As already noted, this line was later taken up by the Indo-Ottoman Telegraph Convention of 1860.

In competition the European & India Junction Telegraph Company was promoted in July 1856 to construct a land line from Seleucia on the Mediterranean coast to Aleppo and Jaber Castle and Kornah "to unite the lines of the English and continental telegraph companies with the cable of the Hon East India Company from Kurrachee to the head of the Persian Gulf". The government in London and the East India Company jointly offered a guarantee of interest of 12% (!) on its capital of £200,000. These generous terms were accepted by the company on February 3, 1857.

The British Parliament in London authorised the Company a capital of £200,000 in twenty thousand shares; half to be allocated to the scrip holders of the Euphrates Valley Railway Company, in proportion of one share of the telegraph company for every five shares in the railway. James Carmichael of the Magnetic and Submarine companies in Britain, and several directors of Indian railway companies were on the board of directors.

The British Treasury was to guarantee £12,000 annually for twenty-five years, or as much as necessary to make the dividend to 6 percent, with a similar amount from the East India Company, on its completion from Seleucia to Kornah, on the confluence of the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. The line was to follow the Euphrates Valley Railway from Seleucia and Aleppo to Jaber Castle, then down the Euphrates river to the Persian Gulf. There was then a line of steamers running down the two rivers to the Gulf.

It was dependent on the completion of the planned cable by the Levant Submarine Telegraph Company from Candia on Crete to Jaffa; lines from Beyrout to Seleucia; and a connection to the Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company at Corfu; or of the Austrian cable from Ragusa to Crete, Alexandria and Jaffa. However, the Ottoman Government rejected the company's proposals in the following September on the grounds that it was, effectively, a British Government-owned concern. Instead the Turks decided in September 1857 to build their own line from Constantinople through Scutari, to Mosul and Bussorah on the Persian Gulf.

The East India Company announced on August 28, 1857 that it would guarantee £20,000 a year for a telegraph cable to India by way of the Red Sea. But it made it clear that it would not support financially any works west of Alexandria. In response to this the Red Sea & India Telegraph Company was promoted as the first attempt to create a 'British' route to India in August 1858 with concessions of the Ottoman Turkish government and its Pashlic of Egypt for through, independent traffic rights. The concessions were those obtained by Lionel Gisborne in 1855, with the support of R S Newall; in the same manner as the Levant Telegraph Company, with which the Red Sea concern intended to connect. It had a capital of £800,000 of which £700,000 was called-up for 200 miles of land line between Alexandria and Suez and 3,048 miles of underwater cable between Suez, Kossier, Suakin, Aden, Hallani (Kooria Mouria Islands), Muscat and Kurrachee in India in six segments. The British government provided shareholders with an unconditional 4½% guarantee for 50 years.

Although not submitting the lowest bid the construction contract went to R S Newall & Company. The line to India was laid on April 12, 1860, but as with the contemporary circuits laid in the Atlantic using Newall's armour, the cables in the Red Sea failed. As they had worked sporadically the state had to continue to pay the guarantee. No traffic to London was ever achieved; although, rather prematurely, the Red Sea company announced on September 9, 1859 messages rates for twenty words from all the Electric Telegraph Company's offices in Britain to Suez, 17s 0d; Kossier £1 4s; Suakin £1 14s; Aden £2 13s; and to all stations in India £2 17s.

Lionel Gisborne, the projector, concession-holder and managing director of both the Levant and Red Sea companies died on January 8, 1861, age 38.Lionel Gisborne and his brother Francis were not related to Frederic Newton Gisborne, who pioneered electric telegraphy in Newfoundland and Canada. Of closely similar ages the former were born and educated in St Petersburg, Russia, the latter in Broughton, Lancashire, England.

The Red Sea company, however, completed the essential two-wire land-line from Alexandria to Suez in April 1859 that was eventually transferred to a new Telegraph to India Company.The Telegraph to India Company was formed in 1861 to assume the rights of the disastrous Red Sea & India Telegraph Company connecting Alexandria in Egypt with Bombay in India. It antici-pated raising and repairing the later company’s cables. It raised a small capital of £45,000 and despatched the Electric Telegraph Company’s senior engineer, Latimer Clark, to Alexandria in January 1862, to be followed by a cargo of 200 miles of replacement cable sent around Africa by ship to Suez. With the eager co-operation of the Viceroy of Egypt, Clark quickly re-established the 220 mile two-wire land line from Alexandria though Cairo to Suez and repaired the initial 200 mile length of underwater cable from Suez to the Island of Jubal at the mouth of the Gulf of Suez by March 7, 1862. A marine telegraph station was established on Jubal to take messages for Europe from the passing steamers of the Peninsular & Oriental Steam Navigation Company travelling to and from India. This little outpost soon turned a profit, sending 2,457 messages by July 2, 1862, earning £170 a week. The Company anticipated using the Arabic language on its land lines and training Egyptians in the use of its instruments. The rest of the ambitions of the Telegraph to India Company proved fruitless - Clark and his assistant J C Laws spent many months surveying and lifting the old cables but found them all irreparable before returning to England in the summer. There was then a half-hearted attempt by Telegraph to India, late in 1862, to create the Syrian Telegraph Company, using land lines to connect its circuit at Cairo with El Arish and Beyrout, with a view to reaching Diarbekhar and Constantinople, raising another £50,000 in capital. That scheme came to nothing.

The abbreviated line from Alexandria to Jubal enabled the Telegraph to India Company to pay 5½ % on its £45,000 capital. The 200 miles of additional cable intended for repairs were sold as surplus. In December 1862 the Jubal station was abandoned as the P&O steamers stopped calling, claiming that it was too dangerous an anchorage, and the Alexandria to Suez land line was leased to Glass, Elliot & Company, the operators of the British government’s Malta to Alexandra cable for £2,500 per year.

Latimer Clark, surveyed the whole Red Sea route to India in 1862. Shortly afterwards he engineered the government’s alternative cable through the Persian Gulf to India. In 1866 an Oriental Telegraph Company, the second concern of that name, proposed to take over the Indian rights but it did not proceed beyond issuing a prospectus. The Suez land line, later still, was acquired by the Eastern Telegraph Company.

With the failure of the multitudinous alternatives the British government paid £436,283 for a 1,400 mile inshore underwater cable between Malta, Tripoli, Benghazi (these latter being Ottoman Turkish cities in North Africa) and Alexandria, opened on September 1, 1861, leasing its operation to Glass, Elliot & Co., its constructors.

The Malta & Alexandria telegraph was project managed by Lionel Gisborne and Henry Charles Forde, a civil engineer. They divided the work between the Gutta Percha Company (the insulated core, £133,841), Glass, Elliot & Company (armouring, shipping and laying the cable, £252,205), and Siemens & Halske (landlines £1,682, instruments, £4,902). Gisborne and Forde and Siemens & Halske took an additional £18,811 for "superintendence". The government in Britain contributed £261,247 and British India £174,493 to the cost. Message rates were 30s 0d for twenty words from Malta to Alexandria; by March 1862 it was carrying 6,000 despatches a month, which earned £12,000. The land circuit through the strife-torn Italian states was, however, slow and inaccurate; the Italians refused to allow Glass, Elliot to use skilled English operators.

Communication was disrupted on May 30, 1864 when the powder magazine at the Ottoman arsenal in Tripoli blew-up, killing "only 150" soldiers. Glass Elliot's telegraph station was levelled but it proved possible to rescue the instruments from the debris.

The problems with the line through Italy from France to the Malta cable continued. The Italians had dismissed their English-speaking clerks in 1864. Disputed messages sent by the Italian circuits between London, Egypt and the Levant multiplied; "as there were so many required their lines were quite 'blocked-up' by them". Instead of addressing the problem the Italians responded by abolishing cheap-rate repetition on November 14, 1864, making recipients pay the full tariff for a new message and a reply.

The government's Malta - Alexandria cable and those of the Extension and Levant companies were acquired in 1868 by the newly formed Anglo-Mediterranean Telegraph Company which was to connect Britain with Egypt by the most direct route and to consolidate the fragmented telegraph interests in the Middle Sea. It also had leased a 1,300 mile land line from Modica in Sicily to Susa in Savoy on the Italian-French border to avoid use of troublesome Italian domestic circuits.

In July 1867 the proprietors of the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, flush with the success of their two long cables between Europe and America, launched the Anglo-Indian Telegraph Company, looking for a capital of £1,000,000 to connect Britain with Bombay, by way of Italy, Egypt and Aden. It came to nothing.The secure cable route to India and Australia was eventually completed in 1872 by a series of British firms that soon merged to form the Eastern Telegraph Company:

• Anglo-Mediterranean Telegraph Company, laying a direct cable from Malta to Alexandria

• British Indian Telegraph Company, laying a cable from Suez to Aden and Bombay

• Falmouth, Gibraltar & Malta Telegraph Company – laying a cable to connect those places

In 1872 the Eastern Telegraph Company with a paid-up capital of £3,400,000, owned 8,860 miles of cable, leased 1,200 miles of land line and had 24 stations.

The Eastern also acquired in 1872 the Marseilles, Algiers & Malta Telegraph Company, a British concern that had finally completed the difficult cable between France and its principal colony of Algeria, with an extension onward to Malta for British use. Many attempts had been made to join Marseilles with Algiers by telegraph but success only came coincidentally with the end of the French Empire in 1871. Of the 300 mile cable, 86 miles had been made by W T Henley in 1867 to cross the Behring Strait between Siberia and Russian America before the project was abandoned. Nothing was wasted!

Separate but in connection with the Eastern company by 1872 were the:

• British Indian Extension Telegraph Company laying a cable from Madras in India to Penang and Singapore on the Malay peninsular

• British-Australian Telegraph Company, laying cables from Singapore to Batavier, from Java to Sumatra, and from Banjoewangie to Port Darwin, Australia, as well as long land lines across the Dutch islands of Java and Sumatra

• China Submarine Telegraph Company, laying a cable from Singapore to Hong Kong

These three soon consolidated into one concern.

Telegraph messages from London to India were latterly subject to a revenue-sharing pool; "Via Eastern", the cable, took 60%, whilst "Via Teheran", the Indo-European land line, took 40% of the income.

1861 - 1868

From ‘The Electrician’

For week-ending December 20, 1861

Paid Range

Red Sea & India Telegraph Company

Shares £20 £18 to £19

Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company

Shares £10 £3½ to £4½

Telegraph to India Company

Shares £1 13s 6d to 22s 6d

For week-ending October 24, 1862

Paid Range

Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company

Shares £10 £3 to £4

Telegraph to India Company

Shares £1 5s 0d to 10s 0d

For week-ending May 1, 1863

Paid Range

Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company

Shares £10 £3 to £4

Telegraph to India Company

Shares £1 5s 0d to 12s 6d

From ‘The Investors’ Manual’

For month ending October 15, 1864

Capital Paid High Low

Mediterranean Telegraph Company

12,000 Shares £10 £3¾ £4

For month ending October 28, 1865

Capital Paid High Low

Allan’s Trans-Atlantic Telegraph Company

15,000 shares £8 £4 ½ £2½

Atlantic Telegraph Company

350 shares £1,000 Last trade £600

5,634 shares £20 Last trade £4 18s

Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company

12,000 shares £10 £4¼ £3¾

3,200 shares £10 Last trade £10

From ‘The Railway News’

For week-ending October 27, 1866

Paid Range

Anglo-American Telegraph Company

Shares £10 £15¾ to £15¾

Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company

Shares £10 £2 to £3

From ‘The Investors’ Manual’

For month ending October 26, 1867

Capital Paid High Low

Anglo-American Telegraph Company

60,000 shares £10 £17⅞ £17⅜

Atlantic Telegraph Company

£462,860 stock £100 £35 £25

600,000 shares £100 £77½ £68

Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company

12,000 shares £10 £2½ £1¾

3,200 shares £10 No market

Telegraph to India Company

45,400 shares £1 Last trade 8s 0d

For month ending October 31, 1868

Capital Paid High Low

Anglo-American Telegraph Company

60,000 shares £10 £22¼ £20¾

Atlantic Telegraph Company

£462,860 stock £100 £31 £32

600,000 shares £100 £84 £78

Anglo-Mediterranean Telegraph Company

26,000 shares £10 £10¼ £9¾

Mediterranean Extension Telegraph Company

12,000 shares £10 £4⅝ £3⅞

3,200 shares £10 No market

La société du câble transatlantique Français

50,000 shares £8 £5½ £2

Telegraph to India Company

42,400 shares £1 Last trade 8s 0d

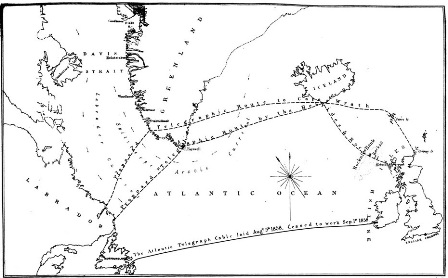

The Atlantic Telegraph Company's route from Ireland to Newfoundland; the North Atlantic Telegraph Company's route from Shetland to Labrador; and the British & Canadian Telegraph Company's route from Scotland to Labrador

(Click on image for larger version, click on Previous Page to resume)

America

The first proposal for connecting Europe and America electrically was that of the Ocean Telegraph Company,

projected in London in the summer of 1852 by C W and J J Harrison of

Surrey in England. It had a capital of £500,000 and proposed an

elaborate route using a series of cables from Britain to North America.

Its prospectus showed that it intended to lay a cable from Caithness in

Scotland to Kirkwall on the Orkneys, another to Lerwick on the

Shetlands, then to Shorshaven on the Faeroes, to Reikiavik on Iceland

with a land-line to Sneefelds, a cable to Graah's Island in Kioge Bay

in Greenland, a land-line to Juliana's Hope, crossing the Davis Straits

from there to Byron's Bay in Labrador, with a long land-line across

Quebec and Lower Canada to the United States. The appalling

terrain of the route suggests the use of an atlas in its planning

rather than survey on the ground. It was to have a total circuit of

2,500 miles of which from 1,400 to 1,600 were to be submarine. A cable

branch was proposed from the Shetlands to Bergen in Norway with a

land-line to Christiania, Stockholm, Gothenburg and a short cable to

Copenhagen. The Ocean Telegraph Company intended to acquire a Royal

Charter to protect its shareholders, but although it was periodically

mentioned in London and Washington until 1856, when it sought the same

subsidy as the Atlantic Telegraph Company, it did not proceed beyond

publicity.

The brothers Charles Weightman Harrison and Joseph John Harrison carried on a very large family business in the way of nursery- and seeds-men at Larkfield Lodge, Richmond, Surrey, and Downham, Norfolk, which had been selling florists' flowers and herbaceous plants nationally since 1834; in connection with which they also published 'The Floricultural Cabinet' magazine. They were more than electrical dilettantes, their first patent was provisionally registered on October 15, 1852 "for the invention of improvements in protecting insulated telegraphic wires" which led to their interest in ocean telegraphy. The brothers acquired further patents for an electro-motor in 1854, for a form of electric light in May 1857 and insulation for telegraph wire in October 1857. They sought capital in 1857, unsuccessfully, for a joint-stock company to exploit the electro-motor. C W Harrison went on to become a dedicated electrical engineer, engaging in the introduction of electric light in the 1870s, before becoming a coal exporter in South Wales.

The Atlantic Telegraph Company was projected in a prospectus issued on November 6, 1856 by Cyrus Field, J W Brett, E O W Whitehouse and C T Bright to construct a telegraphic cable between Ireland and Newfoundland. The Company obtained a Special Act of Parliament with a capital of £350,000 in 350 shares each of £1,000. The Company had offices at 22 Old Broad Street, London EC and 10 Wall Street, New York. As well as Brett and Bright, the Magnetic company contributed George Saward as secretary.

Cyrus Field was a dynamic papermaker from New York in America who became the cable's leading and most determined protagonist. John Watkins Brett had been involved in promoting submarine telegraphy since 1845. Edward Orange Wildman Whitehouse had devised and patented a new telegraph apparatus that could connect the continents; demonstrated it to Brett and had it endorsed by Field and Morse in America. Charles Tilston Bright was then engineer to the British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph, and without question was the most experienced cable engineer in the world.

The British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company took a majority of the shares sold in Britain. It also built a new overhead, roadside circuit from its line at Killarney in Ireland to serve the proposed new cable end on Valentia Island.

The British and United States Governments each guaranteed the Company £14,000 per annum once the cable was successfully completed, reducing to £10,000 each when the dividend achieved 6% per annum. A tariff of £2 10s for twenty words between London and New York was anticipated to be necessary. In return for the subvention the Company was obligated to carry Government traffic free-of-charge.Unlike most companies mentioned in this work, the story of the Atlantic and its successor is one of the management of technology rather than commerce.

Although the Americans subscribed just eighty-eight of the 350 shares they had a disproportionate intervention in the great cable's construction and laying. This led to a catastrophic series of failures in project management; at the Americans' insistence, to accelerate laying, the cable manufacture was rushed through without quality controls; storage facilities were unprepared and inadequate; the manufacturers, R S Newall in Gateshead and Glass, Elliot in London, were given poor specifications which led to the winding of the armour from one being clockwise and that from the other anti-clockwise; and proper testing of the insulation was omitted. There was no co-ordination of the electrical apparatus, so that the operators in Newfoundland did not know what those in Ireland had, or what electrical sources they used.

Not all of the subsequent failures can be blamed on the Americans however. The engineer and promoter, the youthful Charles Bright, whose role clearly should have involved the specification and management of the cable, exercised a distant responsibility. He, allegedly, proposed – based on his own experience and on the scientific recommendations of Thomson and Faraday, that an expensive thick copper core worked by small galvanic batteries ought to be used. Instead the views of Wildman Whitehouse, supported by Cyrus Field and S F B Morse, held sway and a cheaper thin copper core with instruments driven by powerful induction coils was adopted. Bright's actual contribution seems to have been limited to assisting in the design of the cable-laying machinery, principally the work of the mechanical engineer, Charles de Bergue in Manchester. Just about every other matter was left to Whitehouse.

Manufacture of the core and armour of the 2,700 miles of cable still took from February until July 1857.

The cable was laid by two ships starting from the middle of the ocean sailing east and west. After an abortive start on August 7, 1857, a cable was completed between Valentia Island off Ireland and Heart's Content Bay, Newfoundland on August 5, 1858. The insulation of the cable failed irreparably on September 1, 1858. The Atlantic Telegraph Company had to raise a further £112,860 in share capital in London during 1858 to cover the outstanding costs of its expeditions. It then had to find £75,000 to release itself from several obligations that it had entered into with "third parties", the four promoters in London and New York.

The four promoters had awarded themselves one-half of all profits above 10% for their efforts. This was commuted by the Board in 1858 to £75,000 in new shares: Field 37½%, Brett 37½%, Bright 16 2/3% and Whitehouse 8 1/3%; all pocketed as if fully paid-up.

There was a Committee of Inquiry commissioned by Parliament in London. The many engineers and scientists consulted reported in detail on the technical failings, proposed substantial remedies and otherwise endorsed the feasibility of the cable in 1861.

The North Atlantic Telegraph Company was proposed by the American T P Shaffner, a former member of the Morse Syndicate, to adopt the island-hopping route of the Ocean Telegraph Company from Scotland to Orkney, the Faroes, Iceland and Greenland to Labrador or to Belle Isle on mainland Canada, after the failure of the first Atlantic cable. Shaffner launched the company in London and New York in 1859; however confidence in the ultimate success of the long cable was such that it survived only as a shell without capital.

James Wyld, MP and geographer to the Queen, had first acquired a concession of the Danish government for landing rights on Iceland and Greenland in 1852. He was displaced by Shaffner's offer, after promoting the British & Canadian Telegraph Company with the civil engineer, Thomas Page, but he contrived to re-acquire the rights in autumn 1865.

The "Northern Line", as it was called, was taken very seriously after the failure of the 1857 Atlantic cable. James Wyld promoted Acts of the British Parliament and the Canadian Legislature that were passed to raise capital to build the line as the British & Canadian Telegraph Company (Northern Line) during 1859 and 1866. The government in London authorised the 'British North Atlantic Telegraph Expedition' led by the Arctic explorer, Captain Sir Leopold McClintock RN, which set off in August 1860 on HMSBulldog . Suitable points for cable landing were discovered at Thorshaven and Westermanshaven on the Faroes, at Reikiavik on Iceland, at Julianshaab on Greenland, and at Hamilton's Inlet on Labrador in Canada. But it came to nothing as events finally overtook the concern…

The domestic service providers were fully aware of the potential of the American market. From May 1860 the British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company worked in concert with the Atlantic Royal Mail Steam Navigation Company an interim scheme to have public telegraph messages put aboard its heavily-subsidised liners working to Halifax and New York at Galway in Ireland. This saved many days in transit time, particularly as the ships would receive messages almost up to the moment of sailing. It was extended to the ports of Queenstown and Londonderry when the two major steamship lines, Cunard and Inman, agreed to participate. Their fast vessels picked-up and dropped news and public telegraph messages in an exciting procedure using brightly-coloured, waterproof metallic canisters and nets, whilst merely slowing down their speed. The Electric Telegraph Company began a similar service to Canada and America from Queenstown in 1862.By 1863 the Atlantic Telegraph Company had been reorganised. The Americans were entirely displaced from the Board of Directors, which now comprised directors of the Electric and Magnetic companies and representatives of the London investors. The technical department was in the hands of Cromwell Varley, who replaced Charles Bright, supported by a Consulting Committee consisting of William Fairbairn, William Thomson, Charles Wheatstone and Joseph Whitworth.

In America, somewhat forlornly, advocacy

of the cable was left in the hands of Cyrus Field, who never lost his confidence

in the project. He travelled repeatedly across the ocean between New York and

Liverpool to encourage its prospects, and ensured that the long circuit between

desolate Newfoundland and the United States, which he owned, was maintained ready for connection.

The Company issued a new preference capital in London of £600,000, on which the British government guaranteed an 8 per cent dividend "on the completion and during the working of the Cable". Rather than the original £1,000 certificates the capital was democratically divided into £5 shares. Profits above 8 per cent were to go to paying 4 per cent on the 1857 shares, after that to be divided pro rata between the two stocks.

The long and bloody war in America had necessarily postponed progress on the Ireland to Newfoundland cable but in June 1865 further additional capital for its resurrection was arranged by the Atlantic Telegraph Company by means of £250,000 in 8% preference shares. This had to be undertaken through the Credit Foncier & Mobilier of England, of 16 and 17 Cornhill, London, the largest of the new financial intermediaries set up solely to promote joint-stock operations after the Companies Act of 1862. One-fifth of the new shares were allocated to shareholders in the Credit Foncier & Mobilier, one-fifth to those of the Imperial Mercantile Credit, one-fifth to the Atlantic Telegraph Company, one–fifth to the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company, and one-fifth to the public. The chairman of the Credit Foncier & Mobilier, James Stuart Wortley, was also chairman of the Atlantic Telegraph Company. Its principal personality was Albert Grant, the greatest speculator of the age, who failed catastrophically in the 1870s. The finance company, of course, took a large percentage of the stock launch in fees and discounts for organising the placement.

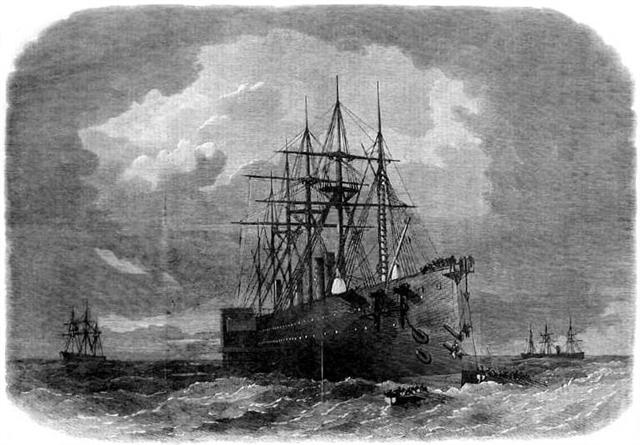

The newly-created firm, the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company, a merger of Glass, Elliot & Company and the Gutta-Percha Company, engaged to lay the Atlantic Telegraph Company's cable. Bearing in mind scientific opinion special care was applied to the manufacture and materials of the cable and TCM took entire responsibility for project management. The cable was to be laid in one length which required the employment of the only vessel capable of carrying such a load, the 18,000 ton Great Eastern.The Great Eastern set off from Valentia on July 15, 1865 steaming west paying-out cable. On August 2 the cable broke in the deepest water. The site of the loss was optimistically buoyed and the ship returned to England.

The Atlantic Telegraph Company immediately proposed to raise yet more capital to complete the great project. It was to do this through the issue of preference shares bearing interest of 12%! However its constitution, embedded in its 1856 Act of Parliament, did not authorise any further issue of shares or creation of debt above that already existing and it stalled.

James Wyld reappeared like the genie from the lamp in the autumn of 1865, along with Thomas Page, with a revival of the North Atlantic Telegraph Company, promoting the "northern line" through Iceland and Greenland. He employed Lewis Cook Hertslet and Nathaniel John Holmes, two former colleagues of Page's, to manage, to engineer and to promote 'his' new North Atlantic company throughout the country. The Great Northern Telegraph Company of Copenhagen eventually took over the Danish concession in 1869, but did not proceed with it.

Confidence in the direct cable was sufficient for contributors to be found to raise a further £250,000 through a new concern, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, quickly formed under the liberal provisions of the Companies Act of 1862. It was a new creation unrelated to the Atlantic concern, and selected the old established firm of American merchants and bankers, J S Morgan & Company, of 22 Old Broad Street, London, to manage its flotation. This firm's board, once again excluding any American influence, except the London-domiciled George Peabody, included Richard Glass and Daniel Gooch of Telegraph Construction & Maintenance, as well as Henry Bewley of the old Gutta-Percha Company. The new Anglo-American company, in which (the reader is asked follow closely here) the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company was by far the majority shareholder, was contracted to act as agent of the Atlantic Telegraph Company in laying and operating the cable. In return, Anglo-American was to receive £125,000 annually from the cable's revenues and another £25,000 annually from the revenues of the New York, Newfoundland & London Telegraph Company, which owned the landing rights in North America – a pleasing 25% reward for the risk. Their confidence, or possibly, their arrogance, was such that Telegraph Construction & Maintenance not only took the contract for making and laying the cable but provided 2,400 miles of new cable in addition to the 1,070 miles left from the previous year, enough for two spans of the ocean, a total of 4,000 tons.

Once again the Great Eastern steamed west from Valentia on July 13, 1866 paying-out as she went and arrived at Heart's Content Bay, Newfoundland on July 27. The Atlantic cable was complete.

SS Great Eastern 1866

The largest ship afloat finds and raises the lost cable

On August 31, 1866 the Great Eastern had returned to the mid-Atlantic and once there its crew found and grappled the 1865 cable! TCM joined it to the remaining wire in its hold and the Great Eastern returned to Heart's Content on September 7. The second Atlantic cable was complete.

The Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company received £190,000 for its work and £55,000 paid in quarterly instalments to guarantee that the two cables remained in good working order. It was also, remember reader, the largest shareholder in the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, which operated the two cables.

With the success of the two cables the old Atlantic Telegraph Company, on September 9, 1866, attempted to modify its authorising Act of Parliament and raise £1,200,000 in new capital with which to buy-out the rights leased to Anglo-American. It failed to find backers in the prevailing financial climate and was condemned to being a vassal of the latter company.

By 1868 the Anglo-American Telegraph Company was paying a 33 1/3 per

cent per annum dividend. The confidence of the the original promoters

of 1856, in particular the long-suffering Cyrus Field, was vindicated.

La Société du câble trans-atlantique Français was promoted in 1867; despite its title it was created under the Companies Acts 1862 and 1867 in London as an English joint-stock company. It was better known as the French Atlantic Telegraph. The Société du câble had a capital of £200,000, issued in ten thousand shares of £20 or 500 francs, to make a cable between Brest in France and the tiny French island enclaves of Sainte Pierre et Miquelon, off Canada, connecting hence by another cable to the United States at Duxbury, Massachusetts.

Paris, like London, was not disposed to give any control of the cable to the United States by landing it on their territory. Not least because of their unwillingness to contribute to the main cost of either project, as well as the belligerence of its government.

The twenty-year concession for the sole rights to the cable was granted by the Emperor to Emile Erlanger and Julius Reuter on July 6, 1868.

Times had changed since 1850 when the Submarine Telegraph Company was created to connect England and France. The ambitious French Empire of Napoleon III needed British capital and technology in this and many other industrial and commercial enterprises. The Anglo-Saxon and German states were regarded as imperial competitors, but unlike France they had experienced manifold industrial expansion. As well as needing capital from London, a market then in chaos, it had to commission English engineers and electricians, mostly from the Electric & International Telegraph Company and the Telegraph Construction & Maintenance Company. It also needed the Great Eastern.The Société's constitution was complex. There was an "Honorary Committee in France", that represented the Imperial Government; the Foreign Minister and three Senators. It addition there was a Board of Directors in Paris under Contre-Amiral Lacapelle, composed of bankers and investors, including Emile Erlanger, loan contractor to the Confederate States of America during their Civil War. Of course, there was a Board of Directors in London, chaired by Robert Lowe, MP. This, too, consisted of investors rather than those from the telegraph industry, including Julius Reuter and the banker William Henry Schröder. Curiously, John Henry Schröder & Company in London had also been a lead banker to the Confederate States.

The ‘Confederate’ connection with the

Great Cable was of long standing. Among the few advocates in Washington of government

support for the 1857 expedition were Senators Judah Philip Benjamin of Louisiana,

and Stephen Russell Mallory of Florida, who became, respectively, Secretary of

State and Secretary of the Navy in the government of the Confederate States. In

1866 J P Benjamin was a lawyer of some eminence practising in London.

The French Atlantic Telegraph had offices at Bartholomew House, Bartholomew Lane in the City of London and at rue Taitbout 20 in Paris. Its "General Superintendent" was James Anderson who had managed the two successful Atlantic cables and who was a director of the British-Indian Submarine Telegraph Company. William Thomson, Latimer Clark and Cromwell Varley, among other British technicians, controlled the mechanical and electrical aspects – all remarkably safe pairs of hands. Robert Slater was company secretary.

Its manufacture and laying by Telegraph Construction & Maintenance and the Great Eastern went without hitch. The French Atlantic Telegraph, the third Atlantic cable, was completed in July 1869 and was the longest in the world until the Pacific was spanned.

The advance of technology was such that Cromwell Varley was able to have this exceptionally long cable 'self-repair' itself using the current to seal damaged insulation; prolonging its life by several years.

As the Electric and Magnetic companies in Britain were contracted to use the cables of the Anglo-American Telegraph Company, the Société du câble agreed with the Submarine Telegraph Company and the United Kingdom Electric Telegraph Company for them to send and receive messages for America from all of their offices in England and Scotland. This brought about an instantaneous reduction in the cable tariff when the longest of all circuits opened on Sunday August 15, 1869!

With the collapse of the French Empire, the Anglo-American Telegraph Company acquired the capital of the Société du câble trans-atlantique Français in 1872. After laying a short cable across the Channel to connect the West-of-England with Brest it worked the cable as one with its system, to the chagrin of the French.

The Great Eastern steamship was to lay five successful cables across the Atlantic Ocean between 1866 and 1874. In between which expeditions she also steamed around the Cape of Good Hope in Africa to India, to lay the cable between Bombay and Aden and into the Red Sea during February 1873, to complete the submarine line between London and Calcutta.

The United States had to wait until the end of the century to have an Atlantic cable land on its territory. Both Britain and France ensured that the western ends of all their cables landed in Canada until then; with only secondary cables or land lines connecting to America.

Smart Cyrus & The Electric Medal

"The American Parliament has passed a resolution of thanks to Mr Cyrus Field, for having made the Electric Telegraph between England and the States, and has ordered a Gold medal to be struck, in honour of Mr Field's single-handed feat. This is quite right. Punch would be the last man to deny that "alone Field did it". We are not quite sure whether he let the water into the space called the Atlantic Ocean, but we know that he invented electricity and telegraphy, and after years of solitary experiments, perfected the Cable which is now laid. He carried it in his own one-horse gig from Greenwich to Ireland, and having previously constructed the machinery for paying it out, launched the Great Eastern by his unaided efforts, lifted the rope on board, and consigned it to the deep with his own hands. Mr Field tied on the Newfoundland end with great neatness, and then ran on with the continuation, and never sat down, nor even blew his nose, until he despatched the first message. Therefore, the medal is his, and the reverse also. But in concession to the ignorant prejudices of the world, might not just the most modest space, say the rim, bear in faint letters the names of Gisborne, Glass, Elliot, Anderson, Canning, and one or two more, who stood by, with their hands in their pockets, and saw the smart Cyrus perform the Herculean task. Anyhow, we do give the ground on which this end of the Cable rests. But we would not press the request, if it would hurt American feelings."

Mr Punch on another manifestation of the 'Morse Syndrome'

March 16, 1867

Politics and Telegraphy

In May 1865 the French Foreign Ministry organised an International

Telegraphic Conference in Paris from amongst the state monopolies in

Europe; Austria, Baden, Bavaria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Greece,

Hamburg, Hanover, Italy, Norway, Netherlands, Portugal, Prussia,

Russia, Saxony, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey and Württemberg.

This was a political-diplomatic initiative between states intended to

integrate the decisions of the Paris and Berlin Conventions of 1855. It

forbad public telegraph companies from its deliberations so the United

Kingdom and the United States, without state monopolies, were excluded

from this and subsequent telegraphic conferences for many years.

The Conference's outcome was a general system of price-fixing based on a zone tariff between the nations, and the setting of the French franc as the common accounting currency. By 1865 the American telegraph was already the standard apparatus in Europe so little technical decision-making was necessary; the Hughes printing machine was added to the international standard by 1872. A substantial permanent bureaucracy was inevitably created at Bern in Switzerland after the final eclipse of the French empire in 1870.

It would, of course, be cynical to suggest that the exclusion of the United Kingdom from the International Telegraph Conference influenced the Government's intention to appropriate the companies.