12. THE COMPANIES AND THE WEATHER

Weather has been

preoccupation of the British for centuries. Britain has "more weather" than

most countries, its seasons are less stable and the seasonal elements more

subject to violent change than continental climates. The weather was clearly

vital to Britain's core economies of agriculture and overseas trade,

particularly when shipping was primarily driven by sail. Its study has occupied

men and women in both rural and urban communities to a surprising degree;

nineteenth century investigators gradually revealed the existence of an immense

regional meteorological archive.

It was the 'Manchester Examiner' newspaper that, during August 1847, organised the very first weather reports by electrical means; "The Corn Market and Telegraph. The weather having been lowering and occasionally wet in the neighbourhood of Manchester during the last two days, and still showery this morning, the anxiety of the commercial classes to know how the agricultural districts were affected, led us to inquire if the electric telegraph was yet extended far enough from Manchester to obtain information from the eastern counties. By the prompt attention of Mr Cox, the superintendent, inquiries were made at the following places; and answers were returned, which we append: Normanton, fine. Derby, very dull. York, fine. Leeds, fine. Nottingham, no rain, but dull and cold. Rugby, rain. Lincoln, moderately fine. Newcastle-upon-Tyne, half-past 12, fine. Scarborough, quarter to 1, fine. Rochdale, 1 o'clock, fair. A glance at the map of England will show that the weather is fine in the chief districts of agriculture east and north of the midlands."

The preoccupation was such that during November 1848, within two years of its creation, the Electric Telegraph Company was sending "weather reports from above forty places in England" to its private subscription news-rooms in Edinburgh, Glasgow, Hull, Liverpool, Leeds, London, Manchester and Newcastle.

And then the 'Daily News' in London, of which Charles Dickens was the first if short-lived editor, began publishing the first regular public weather reports in June 1849. These reports were collected from correspondents on a printed form and forwarded to London by railway express.

It soon became clear to the many individuals interested in the weather that the systematic collection of data, initially for weather maps and then for actual weather forecasts, could be made possible by the electric telegraph, by which data from many distant parts could be brought to one place for analysis in minutes.

In addition to this realisation, new organisation was being applied to meteorological science; on April 3, 1850 the British Meteorological Society was founded in succession to two previous organisations, one dating from 1823. It was not itself a large body growing gradually from 170 members in 1851 to 200 in 1856 and 300 in 1864; drawn from science and the professions, and including several women, but it was to have great influence. Its organising power was its secretary James Glaisher, the Superintendent of Magnetism and Meteorology at the Royal Observatory, Greenwich.

A surprising number of people connected with the telegraph were members of the Meteorological Society by 1862; William Andrews of the United Kingdom company, C T Bright of the Magnetic company, E B Bright of the Magnetic, Samuel Canning of the Atlantic Telegraph, Edwin Clark of the Electric company, Latimer Clark of the Electric, R S Culley of the Electric, J S Fourdrinier of the Electric, Nathaniel Holmes of the Universal company, R S Newall, the submarine cable maker, Julius Reuter, J O N Rutter, who introduced the electric burglar and fire alarm, S W Silver, the maker of cables and insulators, and C V Walker, the telegraphic superintendent of the South Eastern railway who had been a member from its foundation.

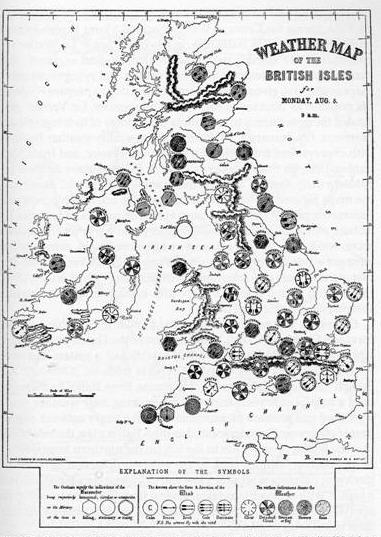

At the Great Exhibition of 1851, inspired by this new interest in meteorology, the Electric Telegraph Company used its circuits to collect the wind direction, the state of the weather and the state the barometer from sixty-four places about the country at the Crystal Palace at 9am each day between August 8 and October 11, 1851 and recorded them on a great meteorological chart with moveable symbols and arrows displayed on its stand. The Company also printed its Weather Map every day on a press by the chart and sold them to visitors for 1d a copy.

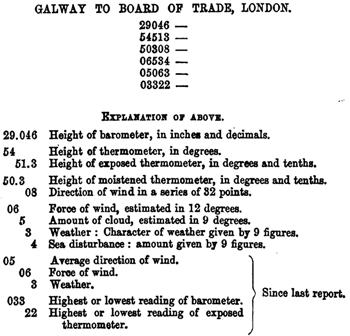

Then in 1859 Admiral Robert Fitzroy introduced a system of Meteorological Telegrams. Weather readings from the coasts along an area bounded by Nairn, Helder and Skuddernaes in the north and north-east, by L'Orient and Rochefort in the south, and by Galway, Valentia and Cape Clear in the west were collected twice a day and telegraphed to a Meteorological Office in London. Here they were inscribed on maps and weather patterns determined. This enabled a day or even two days notice before dangerous winds reached the British seas and ports, as Fitzroy declared 'forecasting the weather'.

Each of the fifteen international coastal reporting stations was equipped with a standard barometer, a wind vane, a dry thermometer and a wet thermometer. At 8am and 1pm every day the station master would transmit the readings of these instruments to London reduced to six groups of five figures. This compressed data included current air pressure, dry temperature, wet temperature, direction of wind, force of wind, cloud, character of weather and sea disturbance, as well as changes since the last report in the direction of wind, highest or lowest temperatures and air pressures.

As the system developed by 1860 'The Times' newspaper was publishing daily weather forecasts, and by 1861 the Meteorological Department of the Board of Trade was co-ordinating the world's first weather service. It was a modest organisation for collecting and diffusing weather data; its annual budget was just £4,600 and the department employed ten people; a scientific officer, an office manager, a telegraphic clerk, a reductions and discussions clerk, a records and stores clerk, a translation clerk, a meteorological instrument clerk, an optical instrument clerk and two messengers. Its offices were at 2, Parliament Street, Westminster.

Each day except Sunday, during 1862 the Department was receiving twenty domestic weather reports each morning, ten additional reports each afternoon and five reports from Europe.

The Meteorological Department issued daily weather forecasts and "double forecasts", two-days in advance, to six daily newspapers, a weekly newspaper, Lloyd's ship insurance market, the Admiralty, the Horse Guards (Army headquarters) and the Board of Trade.

From September 1860, after verification at Kew Gardens, the meteorological instruments, comprising a barometer, a wind vane and two thermometers, for collecting the data were placed in the care of the clerks of the Electric, Magnetic and Submarine Telegraph companies. The clerks "gradually and well acquired the duties asked for (then perfectly new), which are now continued with extremely creditable regularity and precision". The companies' clerks read the instruments and transmitted the short cipher groups summarising the data twice a day to the Meteorological Department. The companies discounted the common message rate by one third for this traffic in the public interest. Competent clerks received 3s 0d extra a week for this work from the Board of Trade.

Sample & Explanation of the Weather

Cypher Messages 1865

Sent by telegraph companies' provincial

stations to the

Meteorological Department in London

During 1864 Storm Signals advising of the severest weather from the Meteorological Department were transmitted by the Electric Telegraph Company to 161 interested parties in 65 places on the coast; and by the Magnetic Telegraph Company to 51 parties in 24 other towns. The recipients were primarily collectors of customs, harbour-masters and those in equivalent positions, including yacht-clubs. In addition the companies' telegraph offices forwarded Storm Signals to their nearest Coast Guard. Included in the distribution by the Electric were Lloyds' insurance market, the 'Shipping Gazette' and the Crystal Palace in London; by the Magnetic, the Ministry of Marine in Paris, the island of Heligoland and the Hanse town of Hamburg.

Starting in 1861 the Coast Guard of the Admiralty on receiving this information had exhibited "cautionary symbols" in public places at coastal towns. In 1862 this covered 130 places, up from 50 in the previous year. When it received the Storm Warnings at ports by telegraph it had hoisted signals in the form of cones and drums on prominent sea-front masts and yards to warn mariners of anticipated foul weather. The Storm Signals were remarkably effective in saving lives and hulls, but were later abandoned as fishermen and other sea-goers objected to the disruption of trade.

In 1870 the telegraph companies' reporting stations in Britain and Ireland were, from north to south, at: Thurso, Wick, Nairn, Aberdeen, Leith, Shields, Scarborough, Yarmouth, Ardrossan, Greencastle, Holyhead, Liverpool, Valentia, Roche's Point, Pembroke, Scilly, Penzance, Plymouth, Portsmouth, and Dover. To which were added reports from London by the clerks in the Meteorological Department, and from Heart's Content in Newfoundland, provided by the clerks of the Atlantic Telegraph Company and transmitted to London without charge.

The following newspapers eventually published the Department's forecasts by 1870: 'Daily News', 'Echo', 'Express', 'Globe', 'Lloyd's Shipping List', 'Observer', 'Pall Mall Gazette', 'Shipping & Mercantile Gazette', 'Standard' (morning and evening editions) and the 'Times' (1st and 2nd editions).

There was some disruption when the Post Office took over the telegraphs in that year; its new offices would not accommodate the meteorological instruments and its staff were stopped from providing data. In many instances volunteers, teachers and retired sailors, had to replace the telegraph companies' clerks.

In competition with the Meteorological Department, as a free public service and, more importantly, to draw in passers-by, the Electric Telegraph Company introduced a Wind & Weather Map at its domestic offices in January 1861. This featured twenty-three coast stations each with a small coloured disc attached, on which were printed the points-of-the-compass and indicators of the wind and weather, fine, strong, rain, and so on. The disc had two rotating hands, one red indicating the wind direction, one white showing the state of the weather. Every day at 8am the twenty-three stations telegraphed their wind and weather to the Central Station where the information was collated and distributed to the several offices so that they could adjust the disc symbols on their maps by 10am.

The Daily Weather Map 1861

With local graphic symbols showing the state of the

Barometer, the Wind and the Weather

(Click on image for larger version, click on Previous Page to resume)

The Daily Weather Map Company was promoted in September 1861 as a joint-stock enterprise with a capital of £4,000 from the offices of the 'St James's Chronicle', at 110 Strand, London. It anticipated selling 5,000 maps a day on a subscription of 4s 0d a month or £2 2s a year, collecting by telegraph and printing weather information from sixty-four stations in England and Ireland. It was not simply a map; it was 'The Daily Weather Map, and Journal of News, Literature and Science'. The prospectus announced "Besides the Map, the publication will contain two pages of letterpress, presenting a carefully prepared epitome of the news of the day, foreign and domestic, with original articles upon topics relating to commerce, agriculture, literature, and popular science. In this department the columns of the Weather Map will furnish the means of intercommunication between all classes of scientific public at home and abroad, and provide a medium through which all discoveries can obtain a wide and immediate publicity. It will thus supply what science has long wanted, and the vast increase in the number of its professors and students so amply deserves, a Daily Organ."

The sets of recording instruments were made by the eminent craftsmen, Negretti & Zambra, to the Greenwich standard of quality and distributed to the stations, and the Map engraved. The firm published two Weather Maps using the same ingenious system of circular symbols for each station that the Electric Telegraph Company had introduced at the Great Exhibition, but was unable to reach its break-even circulation of 3,000 or gain sufficient advertising support. It was projected by James Glaisher, Thomas Sopwith, J W Tripe, Nathaniel Beardmore, Henry Perigal and G J Symons, all active members of the British Meteorological Society. The Weather Map was designed by Thomas Sopwith, grandfather of the British aviation pioneer, and the moveable weather symbols made by the printer George Barclay.

Telegraph, from the Greek “tele”, distant, and “graphos”, writing