23. THE REST OF THE WORLD 1838 - 68

The

following is intended to add some context as to how British telegraph history

fits into the development of communication in Europe and the other continents.

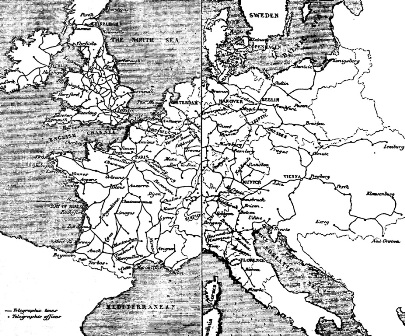

Telegraph Map

1854

A General View of the

Telegraph Network

by which Europe was

overspread at the close of the year 1854

After Dionysius

Lardner

(Click

on image for larger version, click on Previous Page to resume)

a.] Cooke & Wheatstone and the Growth of the Telegraph in Europe

The electric telegraph was introduced to France by Cooke and Wheatstone alongside of the Paris & Versailles railway in 1842; circuits by the Paris & Rouen railway in May 1845 and the Paris & Lille railway in July 1846 followed. The lines were soon absorbed into the administration of the télégraphe aérien, the Bonaparte-era optical system that only worked Government messages; it eventually opened its circuits to the public on March 1, 1851. After the brief experiment with Cook & Wheatstone's two-needle apparatus the state circuits used the Foy-Breguet instrument that copied the indications of the aerial telegraph, but by 1852 the American telegraph, the key-and-register, was being used in all public French circuits.

There had been many successful telegraphic experiments in the German states before Cooke & Wheatstone obtained their first patent in Britain. However, of the first four commercial applications there, three were based on their work.

In 1843 Wheatstone, working with the German engineer Hannibal Moltrecht, installed a short, and short-lived, experimental two-needle telegraph line between Aachen and its suburb of Ronheide, alongside the track of the cable-worked Rheinische Eisenbahngesellschaft, the Rhine Railway Company.

The two subsequent efforts in Germany were also inspired by Cooke & Wheatstone:

William Fardely of Mannheim, who was born

in Yorkshire, successfully installed his adaptation of Wheatstone’s first

capstan and dial telegraph alongside the rails of the Taunusbahn between Frankfurt-am-Main and Kassel in 1844. Like Wheatstone,

Fardely went on to devise an electric clock and to adapt the dial receiver to

print type. Two years later, in May 1846, Johann Wilhelm Wendt, a ship’s master

who had visited Cooke & Wheatstone’s line on the Great Western Railway between

Paddington and Slough in England, organised the Bremer Telegraphenverein with a joint stock capital of 16,000

thalers. He replaced the optical marine telegraph running from the great port

of Bremen to Bremerhaven on the Weser estuary with a two-needle electric telegraph, opening the circuit in November 1846.

The Cooke & Wheatstone two-needle system was the initial public telegraph in Belgium, with a government concession dated December 23, 1845 for a line of telegraph along the Brussels – Antwerp railway. This concession passed, along with all their other rights, to la Compagnie du Télégraphe Électrique, as the Electric Telegraph Company was known in Belgium, which opened the circuit on September 7, 1846 and continued it until September 1, 1850 when it reverted to the state.

In Austria the telegraph was first introduced between the capital, Vienna, and Brunn in Bohemia during December 1846, extended to Prague in September 1847. This used the I & V device of Alexander Bain, modified to work as an acoustic telegraph; and retained in service until 1870. After experimenting with Bain's chemical writer, using sensitized tape, the American telegraph was introduced into Austria between Vienna and Budapest in 1850.

In Italy the electric telegraph was introduced into Tuscany between Leghorn and Pisa in 1847. This used a Breguet dial instrument. It was extended from Pisa to Florence in August 1848. The Cooke & Wheatstone single needle apparatus was adopted on the Piedmont Railway between Turin and Genoa in the Kingdom of Sardinia in April 1852. This railway was created by English engineers, led by I K Brunel. The Wheatstone instruments were used until 1865 in Piedmont-Savoy.

The first electric telegraph in the Netherlands was a Wheatstone dial circuit laid alongside of the Holland Iron Railway between Amsterdam and Haarlem, and opened on May 25, 1845. It was a joint effort of Cooke & Wheatstone and Eduard Wenckebach, who went on to create the state telegraph system in Holland.

During 1853, in Holland the Electric company's subsidiary, the Internationale Telegraaf Compagnie of London acquired a twenty-year monopoly concession for cable and overhead circuits between London and Amsterdam, using, initially, Cooke & Wheatstone's two-needle instruments.

The American Telegraph of the Hamburg-Cuxhaven marine line 1848

This was the first American telegraph in Europe, and came complete with

local relays and batteries of Grove nitric acid cells.

Made by Samuel Winchester Chubbuck of Utica, New York

The American apparatus was introduced into Europe on the Hannoversche Staatsbahn, the Hanover state railway, on its marine telegraph between Hamburg and Cuxhaven in July 1848 by Friedrich Clemens Gerke. This was the fourth electric telegraph line created in Germany. The Elektro-Magnetische Telegraphen Compagnie, a firm of Americans, was contracted to replace an optical system with the electric telegraph. Later Gerke was to adapt the American instrument's cipher to domestic needs, creating "Hamburg Alphabet", better known in Britain when it was adopted in 1855 as the "European Alphabet". It was to become the continental or worldwide telegraphic code.

The first public telegraph in Prussia was constructed by Siemens & Halske between Berlin and Cologne in May 1849, replacing the old optical telegraph. The optical and electro-magnetic apparatus worked in concert as the königlich preussischen Telegraphen-Direktion, the Royal Prussian Telegraph Administration. It used Siemens galvanic dial telegraph, devised by M H Jacobi, and resin-insulated underground circuits on this long line. By 1852 these had been replaced by the American telegraph and overhead lines.

It was in 1850 that what to become the Deutsch-Oesterreichischen Telegraphen- verein was formed to unite the systems of the several German states. This adopted by mutual agreement the American telegraph as its standard instrument, then used only in a small way in Hanover. The Bain I & V telegraphs in Austria, the Kramer and Siemens & Halske dials in Prussia, the Stöhrer magneto-dial in Bavaria, and the dials of Fardely and Stöhrer in Saxony were all then abandoned for public service. It was this decision that made the American telegraph the common system not just in the German states but caused its use to become inevitable throughout the whole of Europe.

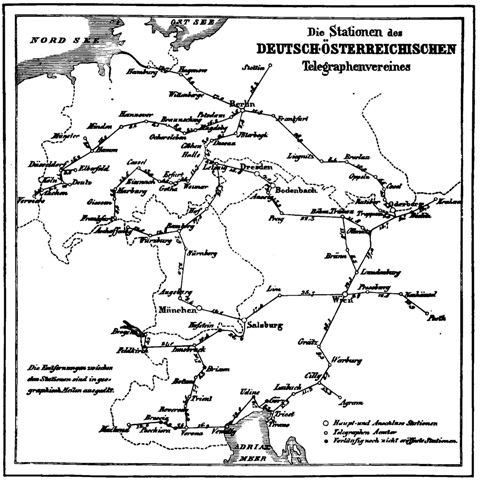

The German Austrian Telegraph Union

A map of the unified electric telegraph system of Austria, Bavaria,

Hanover, Prussia and Saxony as it was in 1852. Of note are the long

strategic lines in Lombardy Venetia, then part of Austria, and the

paucity of lines to the east.

The

lines, all working the American telegraph, are here measured in

Geographical (or Nautical) miles, each of which equals 1 minute of arc

along the Earth’s equator, or 6,080 feet.

(Click

on image for larger version, click on Previous Page to resume)

The first public telegraph in Russia was also constructed by Siemens & Halske, an underground line laid from St Petersburg to Viborg, Helsingfors and Abo in Finland, completed in June 1855 with galvanic dial telegraphs. The Prussian firm had by then contracted to put St Petersburg in circuit with Reval, Riga, Warsaw, Moscow, Kiev, Odessa and Sebastopol, as well as connecting to Prussia at Gumbinnen and Austria at Myslenitz, over many hundreds of miles, an immense undertaking for a single commercial company.

The Electric Telegraph Company of London also created circuits using Cooke & Wheatstone's apparatus in Norway and Denmark, alongside of railway lines built by the contractor, Morton Peto, one of its directors, during 1853 and 1854. These were the first telegraphs in Norway.

The electric telegraph for public service, rather than for experimental or railway use, was introduced in Europe in the following order: Britain 1846, Austria 1849, Prussia 1850, Bavaria 1850, Belgium 1851, France 1851, Baden 1851, Holland 1852, Switzerland 1852, Papal States 1853, Sweden 1853, Wurttemberg 1853, Norway 1854, Denmark 1854, Spain 1855, Russia 1856, Greece 1859, Portugal 1861 and Roumania 1863.

The situation regarding the other Italian states prior to 1865, when a unified telegraph authority was imposed, is unclear. According to 'Annales télégraphiques' the following are the dates of introduction: Tuscany 1847, Lombardy-Venice (then Austrian) 1850, Duchies of Modena, Massa, Carrara and Lucca January 1852, Sardinia (Turin) April 1852, Parma May 1852, the Two Sicilies (Naples) July 1852, Papal States September 1853, and the Two Sicilies (Sicily) 1856.

As well as Cooke and Wheatstone, many European countries had their own telegraphic innovators. There were in the late 1840s the short-lived instruments of Foy, Breguet, Siemens, Fardely, Gloesener, Lippens, Kramer and Stockriss, mostly dial telegraphs developed from Wheatstone's. All of these were to be swept away by the American telegraph, which became the European standard from Portugal to Russia by 1852.

Away from Europe, in British India, the East India Company's, and latterly the government's, circuits, and then the Australian states adopted the American telegraph in 1855, and the American "sounder" shortly afterwards. However the thousands of miles of British- owned and built railways in India, and many in Australia, adopted Cook & Wheatstone's more sophisticated double- and single-needle instruments for traffic control and for internal messaging; just as their iron relatives did in Britain.

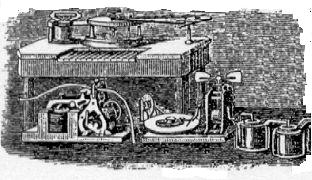

American

Telegraphs in the 1850s

At the back is a

House type-printer, in the foreground to the left is

the common American

telegraph, in the middle a Bain chemical printer,

to the right two

Grove nitric acid cells

Telegraph

Stations in the United States,

the Canadas and Nova Scotia

compiled from reliable sources by Chas B Barr,

Pittsburgh,

Pennsylvania 1853

(Click on image for larger version, click on Previous Page to

resume)

Courtesy of US Library of Congress

b.] The Telegraph in the United States

"In science the credit goes to the man who convinces the world, not to the man to whom the idea first occurs." Sir Francis Darwin, April 1914

In the United States the period before the creation of the Western Union Telegraph Company was dominated by the Morse Syndicate, a small group of lawyers, financiers and legislators that acquired and managed telegraph patents. S F B Morse, by profession a portrait painter with little technical education, was merely a figurehead to this aggressive organisation and, somewhat unfortunately, grew to believe the myths and legends propounded by the Syndicate.

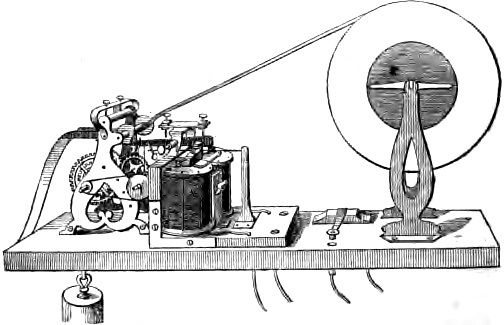

The American

Telegraph 1846

The receiving

Register, left, scratching marks with a needle on a

clockwork-driven moving paper tape; the sending Key, right-centre, a crude

on-off pedal. It required so much

electrical power in operation that it needed a local relay to amplify the

original transmitting current

The assets on which the Syndicate depended were S F B Morse's patents 1,647 of 1840 and 4,453 of 1846. The 1840 patent was used to effect a monopoly of rights to all forms of electric telegraphy, even though the apparatus, the purpose of a patent, was never used. The 1846 patent protected the rights to the American telegraph, with the lever-key, the dot-and-dash marking register and the local relay. None of the three essential elements were devised by the patentee but were "borrowed" from the work of others. For example, the register had been devised and made by Alfred Vail in 1844, who also created the dot-and-dash code that it used.

Morse's name was attached to no other innovations in electric

telegraphy, nor to any useful contributions to science.

The Syndicate was created to make money and not to operate telegraphs. It granted licences to companies and individuals to work the several patents it controlled on a basis of $30 per mile of line and 50% of the stock of the company. It also used its considerable influence in Washington to have the patents renewed for ever longer periods and to gain verdicts in the courts against competitors. Its litigation against Henry O'Rielly (one of its disaffected licensees) and the competitive patents of Royal House and Alexander Bain revealed to the American public a network of agents and interests of mafia-like proportions.

Through this arrangement S F B Morse possessed, he revealed to the Circuit Court of the Eastern District of Pennsylvania in April 1850, $120,000 in stock in the New Orleans & Washington Telegraph Company, $33,000 in the New York, Albany & Buffalo, $4,500 in the Sandusky & Cincinnati, $3,750 in the Maine Telegraph, $12,650 in the St Louis & New Orleans, and $9,300 in the Western Telegraph; he mentioned that he had just sold out his stock in the Magnetic Telegraph Company, between Washington and New York, for a sum, along with other amounts from stock and share dealing, he chose not to reveal. All this stock he acquired without investing a single cent in the companies concerned.

In his deposition S F B Morse curiously styled

himself as “a farmer” of Poughkeepsie, New York.

The other members of the Morse Syndicate,

F O J Smith, Amos Kendall and Alfred Vail, the evidence to the Circuit Court revealed,

had each had taken similar sums out of the patent right business during the

same period.

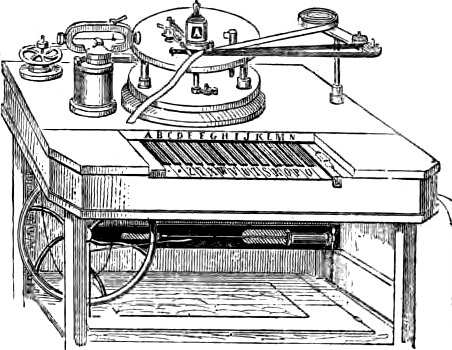

The late model House Type

Printing Telegraph 1850

Suppressed by the

Morse Syndicate when introduced to

the United States in

the early 1850s

The Syndicate bought out the owners of the competitive Bain chemical patents, Henry J Rogers & Company and the North American Telegraph Company, immediately the US Appeals Court found in Bain's favour in 1852. When Henry O'Rielly, who, ever combative, had become the main House licensee, was also bought out, Royal House and David Hughes both protected their interests by selling their patents for sophisticated type-printing telegraphs in November 1855 to the Commercial Printing Telegraph Company, a concern owned by the Associated Press of New York, who used these instruments on their leased press circuits. The Syndicate, in response, encouraged the manufacture of a so-called combination apparatus that only they used, alongside of the key-and-register.

The Morse Syndicate survived only to the end of the patents' extended life in 1858. It had engineered the creation of the American Telegraph Company, which controlled the public telegraph system on the whole East Coast by gradually buying-out the major point-to-point concerns in the area, including those using the House Telegraph, and latterly the Commercial Printing Telegraph Company, with their House and Hughes type-printers.

The 'renegade' telegraph companies in the western states that escaped its net formed, in 1856, the Western Union Telegraph Company and in 1866 that concern absorbed American Telegraph, which had been sorely tried by the necessities of civil war.

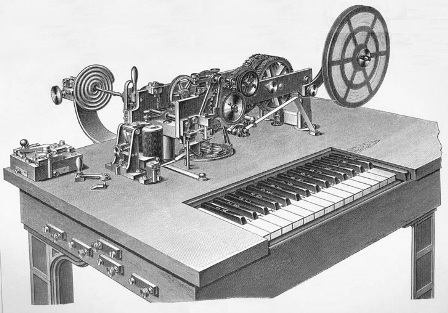

The Hughes Type

Printing Telegraph 1869

Suppressed by the

Morse Syndicate when introduced to

the United

States in the late 1850s

Adopted across the

rest of the World for the longest lines

In 1850 the United States possessed 15,835 miles of line worked under the Morse Syndicate's rights; 2,200 miles under House's patents and 2,012 miles under Bain's. No reliable information exists as to the number of stations opened or messages worked in the fragmented system. There were then 953 miles of telegraph line in British North America.

At the moment in 1866 when the Western Union company acquired the last of its major competitors, the American Telegraph Company and the United States Telegraph Company, its line mileage across the continent had grown to an immense 37,380 miles, with 2,250 stations.

The Morse Syndicate in America in its last gasp used its formidable influence with the US Department of State in 1857 to have it lobby the European powers for "at least $500,000" (£100,000) as the price of the "cost savings" in communications that the introduction of the American telegraph had permitted. It also employed a firm of law agents in France to tout its claims across the continent. Only ten countries responded, led by France, including Russia, Sweden, Belgium, Holland, Austria, Sardinia, Tuscany, the Papal States and Turkey. These, given the lack of any legal justification in the way of patent rights, grudgingly contributed to a box of trinkets in the form of honorary awards and a pot totalling 400,000 francs (£16,000) with which to buy off the Syndicate's agents in Paris, who – in an example of "the biter bit" - took one-third of the sum for all their efforts before passing it on. It was to be payable over four years, from August 1858. In context Cooke & Wheatstone received £70,000 and David Hughes £10,000 just for the British rights to their respective telegraph patents. The Syndicate, and especially its figurehead, was desolate at this "meanness".

Technically

the great difference between the electric telegraphs was that in Europe the

circuits used non-continuous current with weak sources (batteries of cells);

and in America the circuits worked a continuous current and consequently

required much stronger electrical sources. In the United States the line of

wire was always live. British circuits also employed, from the mid-1850s,

double-current or current reversal in the lines that used the American

telegraph, rather than the crude "on-off" key of the United States and Europe.

Although its citizens introduced the advanced and effective House and Hughes

type-printing apparatus (but then quickly suppressed them) the rough- and- ready

nature of telegraphy in America can be judged from the lack of any sort of

galvanometer or detector, automatic telegraphy or even switch-boards in its

circuits until the 1870s.

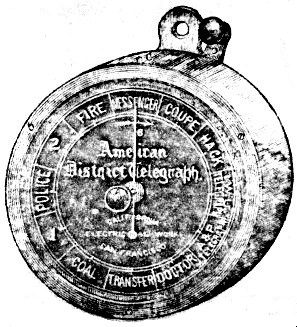

A remarkable American innovation almost wholly ignored in Europe for many years

was the Fire Alarm Telegraph of 1852, and its development the Messenger

Telegraph, by which services, a fire-engine or a parcel carrier, could be

summoned by the public from remote call-boxes in major cities.

W F Cooke and C Wheatstone secured the first patent for electric telegraphy in the United States on June 10, 1840, ten days before S F B Morse. One half of their patent rights were bought by three American partners.

The American

District Telegraph

Located in public

places, this allowed individuals to summon services and suppliers; here in San

Francisco, California, are Messenger, Coupe (open cab), Hack (closed cab),

Western Union Telegraph, A&P Telegraph, Doctor,

Transfer (?), Coal,

Number 1, Police, Number 2, and Fire (Brigade)

There was nothing

like it in Europe

c.] A Statistical Comparison of the World's Telegraphs 1869

The following statistical comparison is drawn from the information on the world-wide state of telegraphy tabulated in 1869 by George Sauer. The raw information that was gathered through US Embassies varied greatly in response and quality, so only a partial guide to development was possible.

The Austrian Empire and the Electric & International Telegraph Company did not bother to reply.

Belgium 1851 *

257 miles; 10 offices; 14,025 messages

Belgium 1867 *

2,424 miles; 374 offices; 1,293,870 messages

France 1851 *

1,325 miles; 17 offices; 9,014 messages

France 1867 *

23,090 miles; 1,486 offices; 3,213,995 messages

Norway 1855 *

471 miles; 22 offices; 22,916 messages

Norway 1866 *

2,205 miles; 73 offices; 269,375 messages

Prussia 1852 *

2,070 miles; 48 offices; 48,751 messages

Prussia 1867

13,364 miles; 857 offices; 2,582,460 messages

Russia 1857

4,840 miles; 79 offices; 133,538 messages

Russia 1864

21,119 miles; 308 offices; 838,653 messages

Switzerland 1851 *

1,000 miles (est.); 34 offices; 2,876 messages

Switzerland 1867

2,395 miles; 333 offices; 708,974 messages

United Kingdom 1850 (Company sources)

2,215 miles; 257 offices; 64,734 messages

United Kingdom 1868 (Government returns)

16,879 miles; 3,381 offices; 6,438,392 messages

Sauer's Miscellaneous Returns

Australia 1865 - 3,100 miles; 79 offices

Austria 1851 - 2,175 miles; 45 offices (author)

Denmark 1867 - 950 miles

Egypt 1867 - 1,747 miles

Holland 1867 - 1,447 miles; 194 offices

India 1866 - 13,390 miles; 174 offices

Italy 1869 - 9,927 miles; 1,065 offices

Spain 1867 - 6,670 miles

Sweden 1867 - 3,519 miles; 257 offices

Turkey 1863 - 4,032 miles; 52 offices

Turkey 1867 - 17,087 miles; 310 offices

Miles here refers to miles of line. The * indicates an operating loss. Twenty-five per cent of messages in the French telegraphic system were on behalf of the Government; forty per cent of Belgian messages were 'transit' traffic from other countries.

Most of the continental state telegraphs at this time had a zone (distance) tariff for a standard message (either fifteen or twenty-five words, with five word increments), charging as well for addresses and for delivery outside of the destination town. A one hundred word limit was commonly imposed on public messages.

Every sort of Government traffic, even the most trivial, had priority over the

public. In France and Russia all messages had to be inspected before

transmission by an official for "objectionable" matter.

In many Continental countries there were railway telegraphs working public traffic to and from their passenger stations outside of the main Government systems, mostly using dial equipment rather than the American telegraph. The largest of these was probably La Grande Société Russe des Chemins der Fer, an Anglo-French company founded in 1857, which owned 2,693 miles of railway in Russia by 1868, and worked the Siemens magneto-electric dial telegraph throughout its system.

The railways of the German states finally abandoned the Siemens dial telegraph for the American telegraph on the re-creation of the unified Empire in 1871.

As well as the Rijkstelegraaf in Holland in this period there also existed two small regional joint-stock companies, carrying 6% of public message traffic in 1860, compared with the state's 92%; the balance was borne by the railway telegraphs.

The Rijkstelegraaf had 63 offices in 1863, with 145 instruments, employing 253 officials and

89 messengers. In that year it managed 653,261 messages. The competitive

Netherlands Telegraph Company, with three stations between Rotterdam and

Nieuwediep, then had a traffic of 19,205 messages; and the Rotterdam Telegraph

Company with a small network of five stations between Rotterdam and

Brouwershaven, carried 12,130 messages. The public telegraphs of the Holland

Iron Railway, with nine stations, carried 9,206 messages, those of the

Dutch-Rhenish Railway, nine stations, 1,503 messages, and the Maastricht-Aachen

Railway, five stations, 266 messages.

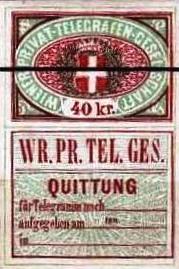

Wiener Privat-Telegraphen-Gesellschaft

Stamp & Receipt 1870

40 kreuzer tariff to forward a 20 word message to another system

The frank at the top attached to the message form,

the receipt beneath was filled-in and torn off

The Wiener

Privat-Telegraphen-Gesellschaft (WPTG) was formed in Austria during 1869 with a

capital of 200,000 florins (£20,000), having a Central Bureau at Friedrichstrasse 6, Vienna.

It was to possess a very large network within Vienna and its outskirts. In 1874

there were a total of 88 private stations, covering the Inner or Old City, the

Vorstadt and the Suburbs; including 15 banks, 10 hotels, 10 post offices, 4

hospitals and sanatoria, 4 major factories, 3 steamboat operators on the Danube,

2 newspapers, a brewery, and the railway

stations of the Südbahn and Westbahn, as well as secondary agencies for message-forwarding.

It was organised in a similar manner to the London District Telegraph Company.

The WPTG tariff had a base message rate

for up to 20 words of 25 kreuzer (6d) between any of its own stations. There was

an additional charge for forwarding by the State or railway telegraphs to their

stations in Vienna of 15 kreuzer (c. 3½d) and 25 kreuzer (6d) to telegraph

stations outside of the city and its environs.

Telegraph, from the Greek “tele”, distant, and “graphos”, writing