11. THE COMPANIES AND THE NEWS

|

The relationship between the press and the telegraph companies in Britain was

discrete. Unlike in the United States where the press was extraordinarily

active in promoting telegraphy and organising news-gathering and news

distribution, in Britain the press was initially cautious and then became

hostile. The sole exception to this antagonism was the considerable personality

of Julius Reuter.

In the period described, between 1845 and 1870, the British press was

divided between that of London and that of the Provinces. The eight or so

London daily morning and evening papers were large organisations, with a

variety of specialist correspondents. At first confined to the metropolis the

railways had just started to distribute the London morning newspapers nationally

on the day of issue, much to the detriment of local competition. As with the

telegraph the papers showed their helplessness when faced with new technology

by ignoring the potential for increased distribution, leaving it to

third-parties. In 1845 W H Smith & Son, wholesale news agents, were sending

packages of London journals to nine distant cities by railway so that they

arrived in the morning, albeit the late morning. The railway companies working

out of London joined in, offering subscribers close to their stations the

metropolitan papers delivered by their porters in the morning. Both added ¼d to

the 4d or 6d cover price. The papers metaphorically wrung their hands but did

nothing for many years. It was to be W H Smith, rather than any newspaper owner,

who became a shareholder in and director of the Electric Telegraph Company.

However, all

provincial cities and towns throughout the United Kingdom had their own daily

paper, many of formidable influence, but these lacked the resources of those in

London in regard to news-acquisition. They relied, before 1845, on a mass of

corresponding agents in the capital to forward them by post such national and

foreign information that they could gather. These agents were rewarded, by

the newspapers in the larger towns and cities, with advertising space that

they could sell on, rather than money, demonstrating the peculiar “cashless” nature of the newspaper business.

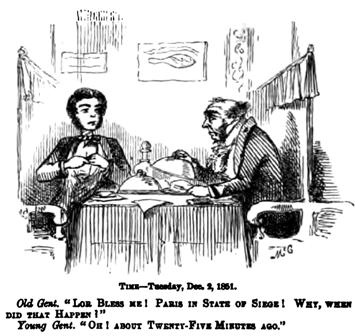

The first telegraphic newspaper report in Britain appeared in the ‘Morning

Chronicle’ in London on May 8, 1845. It was a prosaic piece recording a meeting

of railway proprietors in Portsmouth.

Humbug “The first duty of the

Press is to obtain the earliest and most

“Your telegraphic

summaries of foreign intelligence |

The Intelligence Department

The Electric Telegraph

Company organised the first systematic news dissemination service in April

1848. This dealt with just sports (horse-racing results) and exchange (market

price) news. It was subscribed to by provincial papers, news-rooms, clubs and public

houses and, before public messages became popular, was the Company’s largest

traffic for many years.

Charles Vincent Boys, known in Fleet Street as ‘CVB’, had charge of the “Intelligence Department” of the Company, as it was called, through its entire twenty-two year existence from 1848 until 1870. His age on appointment was twenty-three. By the end of this period ‘CVB’ was third or fourth ranked in the management of the Electric Telegraph Company, demonstrating the importance of ‘Intelligence’ to the organisation.

Intelligence provided subsequently, in the mid-1850s, comprised a Parliamentary Summary, Court & Society Gossip, General News, Commercial News, Sporting News, Law Reports and Weather Reports. The information was culled by the Company’s superintendent and his four news-clerks from London newspapers and foreign telegrams, and edited into bulletins, at a cost to provincial subscribers in the early years of between £150 and £250 per annum. The Company believed in volume as 4,000 words a day were supplied to newspapers, news-rooms and hotels, increasing to 6,000 words a day when Parliament was in session. The summary was sent to the provinces overnight before 7am with another bulletin at 6pm, as well as updates on prices, shipping and parliament during the day.

Of particular importance in the earliest days of the Intelligence Department were news-rooms, whether belonging to the Company, to exchanges and markets, to literary and educational associations, to hotels or to individual proprietors. These gave subscribers daily access to a range of printed publications and, from 1848, regular news reports through the day by telegraph before they appeared in the press.

The depth and regularity of the intelligence provided by the Company to its news-room subscribers from the earliest days is shown below – the aggregation and study of data in market-making is as old as the market itself...

The Electric Telegraph

Company’s

Subscription Room

Exchange Arcade, Manchester, Dec 5, 1848

In the News Room Department, the tables are supplied with the London and Provincial journals, periodicals, prices current, &c. with promptitude and regularity.

In the Intelligence

Department, the information brought by the Company’s Expresses is

regularly posted for the use of the subscribers. The following are some of the

principal expresses, and times of their daily arrival, save when otherwise

stated:

• Wind and

Weather from most of the principal towns in the kingdom, 9.0am

• Morning

Express, containing the city and parliamentary intelligence of the preceding

evening and general news up to an early hour in the morning, 9.30am

• Liverpool

and Hull Shipping, 11.0am

• Liverpool

Cotton Market (first report), 12.15pm

• Lloyd’s

List, 12.30pm

• Leeds,

Liverpool and Birmingham Share Markets, 12.30pm

• London

Corn and Cattle Markets (Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays), 12.45

• London

Share List and Money Market, 1.0pm

• Wakefield

Corn Market (Friday), 1.30pm

• Afternoon

Express, containing news brought by the Paris and Continental mails, which

arrive in London in the forenoon, 2.0pm

• Liverpool

Corn Market (Tuesday and Fridays), 2.0pm

• Leeds

Corn Market (Tuesday), 2.15pm

• Leeds

Cloth Market (Tuesdays and Saturdays), 2.15pm

• Newark

Corn Market (Wednesdays), 2.30pm

• Liverpool

Cotton Market (close), 2.30pm

• Hull Corn

Market (Tuesdays), 3.30pm

• Newcastle

Corn market (Tuesdays and Saturdays), 3.0pm

• Liverpool

Share Market (close), 3.30pm

• Leeds

Share Market (close), 3.30pm

• London

Share and Money Markets (close), 4.0pm

• Evening

Express, containing any important occurrences which have transpired during the

day, 5.0pm

In addition to the above, the arrival of the Foreign and Irish Mails at Liverpool, London, Southampton, Hull, &c. is immediately posted, with a condensed report of the information brought by them; and the arrangements of the company are such that no event of importance can occur without information of it being in Manchester many hours in advance of the ordinary methods of communication.

Subscriptions for the year 1849 may now be paid, admitting to all the company’s rooms throughout the kingdom – Single subscription, two guineas; for every additional member of the same firm, one guinea.

The Subscription Room is open from eight in the morning till nine in the evening.

The importance of the news-room may be judged from the Manchester Athenæum for the advancement and diffusion of knowledge, founded in 1836.

The Athenæum club house at Bond Street included a news-room, a library, lecture rooms, gymnastic and drama clubs. In 1855 it had 1,114 members, mostly working men, who paid 24s 0d a year subscription. The news-room, used principally in the evenings at the end of the working day, was the busiest and most expensive of its facilities. From its total annual income of £1,823 in 1855 the news-room spent £273 on newspapers, on nearly 200 of the Manchester and London dailies, the weeklies, Irish, Scottish and English provincials, and French, German and American journals, and, most worryingly for the newspaper owners, an additional £57 for the latest, almost hourly, intelligence by telegraph. In comparison the Athenæum’s large Library spent £82 on new books and magazines.

An example of a

typical private news-room, from the resort town of Brighton in 1864, shows that

it was “liberally supplied with all the London and local newspapers, reviews,

magazines, literary journals, railway records, share lists, army and navy

lists, peerages, court calendars, directories and other publications and maps,

so frequently required for reference. Electric telegraph news of any

importance, and the prices of English and Foreign funds and railway shares, are

received and posted in the rooms at different hours of the day for the

exclusive inspection of Subscribers. The Subscribers to these rooms have also

the advantage of Reuter’s foreign telegrams, which are regularly received and

posted in the Rooms.” There were writing tables and materials available, too.

The subscription in 1864 was annually 26s 0d, half-yearly 15s 0d, quarterly 10s

6d, monthly 6s 0d and for a week 2s 6d.

The last and largest of such facilities was the Lombard Exchange and News Room that opened for business on January 1, 1869. It occupied the ground floor of the huge City Offices building at 39-41 Lombard Street, on the corner with Gracechurch Street, built in 1868. It possessed a business and news-room of 7,200 square feet, its own telegraph instrument room, a dining-room and luncheon-bar at one end, with a smaller writing room upstairs. Within six months it had a membership of 1,596, each paying an annual subscription of £3 3s, who had access to newspapers, directories and maps, as well as instant telegraphic news and prices. Individuals could also use it as their place of business, able to deal in shares and stock and commodities on its floor. Its message traffic was such that a pneumatic tube was planned to connect with the Electric Telegraph Company’s station at Telegraph Street, instead of an overloaded private wire.

Regarding exchange news, the Intelligence Department provided the substantial

Stock Markets in Manchester and Liverpool with the London’s noon and closing

prices from 1848, and took their business numbers for the London newspapers; of

importance then were those for railway shares and Government funds.

During 1851 the Liverpool Stock Market was complaining about the irregularity

of the exchange intelligence it was receiving and negotiated a lower

subscription. Early in 1854 the Liverpool market dropped the Electric’s

exchange service for that of its competitor, the Liverpool-based Magnetic

company. In April 1854, the Manchester Stock Market followed suit. It is worth

noting that the railway share market on the Liverpool exchange was greater in

volume at this time than London, and that Manchester was a strong third in the

seven English stock and share markets.

The Electric was quoting the Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds stock

market prices as well as those of London in its exchange news circulated to

provincial subscribers during 1849; a service seized upon by stock speculators,

creating as well a new dealing speciality, the inter-market arbitrageur.

It was the sporting press that took to the telegraph with real enthusiasm: ‘Bell’s Life in London’ and other lesser sports papers, dealing with results of races and matches on which wagers were made, were soon sending messages concealed in a private key so that no advantage could be gained by intercepting them. The famous turf editor of ‘Bell’s Life’, William Ruff, contracted with the Electric company in 1852 an annual arrangement by which he and his reporters at the race courses received books of passes to pay for their messages giving results on account, without needing cash. Previously Ruff had used road coaches and pigeons to return results, but “the pigeons were often shot”.

Other newspaper reporters also carried pass-books paid for by their papers rather than use cash for sending news by electric telegraph.

An exception was the “aerial telegraph” at Goodwood Races, where the course’s owner, the Duke of Richmond, refused to allow telegraph poles on his lands. The Electric Telegraph Company kept 40 pigeons at its Chichester station to carry messages from Goodwood.

The Company was remarkably enthusiastic about supporting horse racing. Special wires were opened in the early 1850s to temporary telegraph offices in the grandstands at the fashionable courses of York, Chester, Doncaster and Epsom, even to lowly Brighton, on race days for press reports, tipsters and betting. But, as with aristocratic Goodwood, the headquarters of racing, Newmarket, would have none of it; messages had to be sent and received at the railway station. The Company even offered specially reduced rates from race courses in September 1853. To further accommodate the market, in November of the same year the Company’s R S Culley agreed to replace the unsightly overhead circuits at Chester race course with much more expensive “wires buried in the earth”. Coincidentally, C V Boys, superintendent of the Intelligence Department, was said to take a close interest in racing information...

William Ruff provided the telegraph company with all the horse racing results he compiled daily for sending to the provincial press. When the government tried to suppress off-course betting-offices in January 1854 the Electric Telegraph Company stopped reporting racing results for some years.

To fill the need William Wright, sporting printer and publisher, of 9 & 10 Fulwood’s Rents, High Holborn, producer of the daily ‘London Betting Price Current’ set himself up as an “electric telegraph agent”. From 1853 he distributed ‘Tattersall’s Betting and Results of Races’ and ‘Racecourse Information’, the latter with arrivals of horses, scratching, order of running, betting before going to the course, betting on the course, and betting at midday at Beeton’s, to private subscribers daily by electric telegraph for well over ten years. Each of Wright’s messages, concealed in a private key or code, cost 3s 0d.

By February 1867, the enterprising Wright, now styled “sporting printer, publisher, commission and telegram agency”, of the Handicaps Book Office, 16 York Street, Covent Garden, was advertising to bookmakers as “having the telegraph laid on to his premises”.

Samuel Powell Beeton, father-in-law to Mrs Isabella Beeton of ‘Household Economy’ fame, had opened an off-course betting market at his public house, the Dolphin, 39 Milk Street, Cheapside, in competition with the ‘aristocratic’ market at Tattersall’s during April 1851. He quickly acquired 200 ‘members’, other publicans, betting-office owners and private betting commission agents, who laid the racing odds personally and by post and by telegraph.

The awful army of racing tipsters, who advertised intensely in the sporting press in the nineteenth century, followed Wright’s example in using the telegraph.

In 1854 it was noted

how the provincial daily press was served by the Electric’s Intelligence

Department: “At seven in the morning the clerks are to be seen deep in the

‘Times’ and other daily papers, just hot from the press, making extracts and

condensing into short paragraphs all the most important news, which are

immediately transmitted to the country papers to form the second editions.

Neither does the work stop there, for no sooner is a second edition published

in London than its news, if of more than ordinary interest, is transmitted to

the provinces”.

The busiest time was on Friday nights when the London and continental news was

‘condensed’ for the so-called ‘Saturday’ provincial papers; these weeklies had

the largest circulations in the country as they were actually intended to be

read on the one day-of-rest, on Sundays. The printing and distribution of

papers on the Sabbath was forbidden, if not illegal.

In 1855 the Company came to an agreement with ‘The Times’ newspaper to

receive its news messages from abroad without charge to the sender in exchange

for rights to sell them in the provinces.

In 1858 163 of the 1,200 daily and weekly provincial newspapers subscribed to

the Electric’s Intelligence Department; up from 120 in 1854. It was also

forwarding news to news-rooms, hotels and individual journalists. This

relatively low up-take was despite rates 25% less than ordinary messages when

sent during the day and 50% less when sent at night, with a further 25%

discount for delivery to additional addresses in the same town.

By December 1861 the Intelligence Department was contracted to supply information to 175 newspapers and to 99 institutions with news-rooms.

Newspapers in Glasgow, Edinburgh, Newcastle, Manchester and Liverpool leased dedicated circuits at the Electric Telegraph Company’s London offices at night, when public traffic was light, by which they could send and receive their own news-copy using the Company’s clerks. The Company’s messengers delivered the “slips” with the news messages to the newspaper offices. In 1867 four Scottish newspapers each had a special night wire between London and Scotland; the ‘Scotsman’ and the ‘Daily Review’ in Edinburgh, and the ‘Glasgow Herald’ and the ‘Glasgow Daily Mail’. Latterly, when other telegraph companies joined the news pool in 1865, the Scottish press preferred the Hughes type printer on their circuits.

In Dublin, by 1869, the ‘Irish Times’ had a Special Wire, and the ‘Freeman’s Journal’ and ‘Saunders’s Newsletter’ shared the use of a press wire. The ‘Scotsman’ and ‘Glasgow Herald’ paid to have the telegraph on their premises, much against the better judgement of the telegraph companies who feared all manner of fraud and deception. The wire for the ‘Scotsman’ was leased of the Electric company; those for the ‘Edinburgh Review’ and ‘Glasgow Herald’ of the Magnetic company; and for the ‘Glasgow Mail’ of the United Kingdom company. The Dublin wires were provided by the Magnetic.

The Telegraph Newspaper 1864

From an article also

titled ‘My Newspaper’ in

Charles Dickens’s

magazine, ‘All the Year Round’, June 25, 1864

I proceeded to a suite of rooms occupied by the sub-editor and the principal reporters. In the outermost of these rooms is arranged the electric telegraph apparatus – three round discs with finger-stops sticking out from them like concertina stops, and a needle pointing to alphabetic letters on the surface of the dial. One of these dials corresponds with the House of Commons, another with Mr Reuter’s telegraph office, the third with private residence of the conductor of my journal, who is thus made acquainted with any important news which may transpire before he arrives at, or after he leaves, the office. The electric telegraph – an enormous boon to all newspaper men – is especially beneficial to the sub-editor; by its aid he can place before the expectant leader writer the summary of the great speech in a debate, or the momentous telegram which is to furnish the theme for triumphant jubilee or virtuous indignation; by its aid he can “make-up” the paper – that is, see exactly how much composed matter will have to be left “standing-over,” for the tinkling of the bell announces a message from the head of the reporting staff in the House to the effect, “House up – half a column to come”.

This refers to the new ‘Daily

Telegraph’ paper, the first mass-market journal

in Britain, which had a price of

1d, when ‘The Times’ was 6d

The Competition

During

1853 the Submarine & European Telegraph Companies jointly maintained a

small News Department which contracted with the Agence Havas,

a general news agent at Paris, to supply them with a summary of continental

news in the afternoon at a fixed price. This it distributed to the gentleman’s

clubs and to some daily newspapers in London. They originally undertook this to

generate publicity rather than as a general service. However from March 1855

the British Telegraph Company, which acquired the European concern, continued

the provision and extended it to subscribing newspapers in the north of the

country, providing a single daily Telegraphic Despatch of

foreign news from Havas.

The Magnetic Telegraph Company managed news on a different model. Firstly, it

offered recognised news correspondents a day rate of 6d for nine words between

any two stations or a night-message rate for long despatches of one-tenth that

for the public. Secondly, it provided news by contract to newspapers and

news-rooms throughout Britain and Ireland at a cost of between ¼d and ½d a line

of ten words, providing daily the equivalent of two whole broadsheet newspaper

columns of information. It achieved the latter through a News Exchange in

Liverpool to which all the subscribers contributed and from which a

consolidated, common news selection was received in return. It also had paid

agents, news-collectors and parliamentary reporters.

The Magnetic provided share, corn, cotton, coal, iron, cattle, provision and

produce market prices, information on fairs, shipping arrivals, foreign and

domestic news, ‘gazette’ (government and legal) news and parliamentary reports;

much as the Electric’s Intelligence Department. It also leased a private wire

from London to ‘The Freeman’s Journal’ newspaper in Dublin.

This merged with the British company’s News Department in 1857, much improving its foreign sources as it then had access to Paris and the news resources of the Agence Havas.

The British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company had a special contract with Lloyd’s of London, dating from April 1861 for which it was paid £250 per annum. It collected in London details of shipping “casualties” from Lloyd’s agents and correspondents in Britain and on the continent, arrivals and departures of shipping at Liverpool, arrivals and departures at Gravesend and at Deal, and received messages from Lloyd’s agents throughout the country. As well passing all this intelligence to Lloyd’s it was permitted to add its details to the daily public news despatches. In addition, it collected for Lloyd’s exclusive use information on European shipping “casualties” in American waters from ships speaking with its coastal stations at Queenstown, Galway and Londonderry.

The Magnetic company performed a great telegraphic news feat during the evening of Sunday, December 27, 1857. President James Buchanan’s 13,654 word first annual message was delivered in Washington in America on December 8, 1857. A copy of the speech arrived at Liverpool on the Cunard liner Africa at 6 o’clock on December 27. It was telegraphed to London by the Magnetic in 300 minutes, and was in the hands of the printers of the London newspapers by 11 o’clock; appearing in ten whole columns of their Monday editions. This was twice the length of the previous longest message.

The News Combination

The Electric and the Magnetic combined

their news operations, continuing the title of the Intelligence Department, at

the latter’s new Central Station during January 1859, and, abandoning the Agence

Havas, contracted jointly with Julius Reuter to buy his foreign news

telegrams to transmit to the provinces for £800 per annum. Reuter retained the

right to despatch foreign, commercial and shipping news to the much larger and

wealthier London daily and evening papers and his private subscribers within

fifteen miles of London. In February 1865 the United Kingdom company joined the

Intelligence Department pool; the revenues were divided up in proportion to

their total public message turnover.

The combined companies issued “Intelligence Instructions” to clerks with its arbitrary two-letter codes for transmitting statistical information such as Share Lists, State of the Weather, Bank Returns of debt, money and coin, the Corn Market and the Cattle Market.

There was a warning code for Special Express Messages for news of the greatest importance that gave them priority over all others. The code for so-called ‘Expresses’ had to be authorised by the department’s superintendent from Founders’ Court.

The weather was reported from Aberdeen, Belfast, Brighton, Cardiff, Cape Clear, Deal, Dublin, Dundee, Falmouth, Gravesend, Greenock, Hartlepool West, Holyhead, Hull, Leith, Liverpool, Londonderry, Milford Haven, Penzance, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Queenstown, Ramsgate, Shields, Swansea, Valentia, Whitehaven and Yarmouth. Independent of the government’s Meteorological Department, it consisted of ten two-letter codes.

Charles Dickens’ magazine, ‘All the Year Round’, during 1868 reported that the Intelligence Department issued “a jumbled piecemeal of items sent from the thirty instruments of the Threadneedle Street office. No sounds heard save the intermittent click of the handles of the instruments, and the shrill, tumultuous rhythm of the bells”. Not a ringing endorsement of the companies’ news provision – but then Dickens at heart was still a journalist…

The provincial newspaper owners and their parochial editors complained to Parliament that they wanted racing results and not the tedious details of foreign wars and politics that the Intelligence Department provided. The telegraph companies had the papers subscribe to separate contracts, over and above those for intelligence, to receive valuable sporting news and results.

However, according to Edward Bright during 1868 the telegraph companies were supplying bulletins to about 400 subscribers; and the income to companies from these activities was over £20,000 per annum. According to government reports in 1868 the Intelligence Department sent news to 306 subscribers, including 173 newspapers, in 144 towns.

There were then four services provided: 1] general intelligence, 4,000 words a day including Reuter’s foreign news; 2] special wires from the telegraph offices in London over which the papers provided their own news; 3] sporting news; and 4] special messages at a discounted rate for the newspapers’ roving correspondents.

Outside of the daily General Intelligence by subscription the Intelligence Rates by the combined companies for Special Messages in 1865 were; between 7am and 7pm, the tariff rates but allowing 30 words rather than 20 words, and half rate for the next 15 words and above rather than 10; between 7pm and 7am, the tariff rates but allowing 40 words rather than 20 words, and half rates for 20 words rather than 10. There was a 200 word limit on copy sent, unless previously authorised by London. To avoid hoaxes prepayment in cash or stamps was required by most newspapers.

In the late 1860s only twenty-four of around 140 subscribing provincial news-papers, thirteen dailies and eleven weeklies, used the Companies’ Special Messages, spending in all a paltry £280 a year on such telegrams to obtain news from London.

|

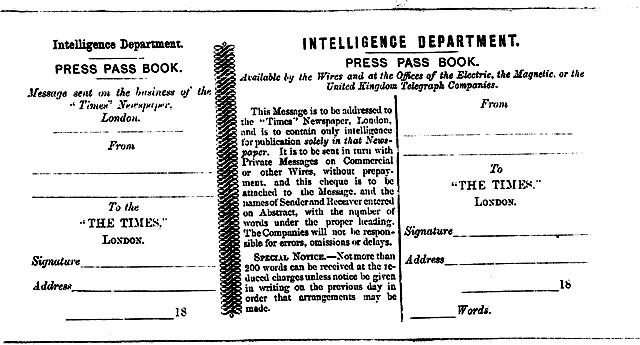

Telegraph Company Press Pass

The nine London papers, the ‘Globe’, ‘Daily Telegraph’, ‘Star’, ‘Glowworm’ (sic), ‘Morning Advertiser’, ‘Shipping Gazette’, ‘Morning Post’, ‘Pall Mall Gazette’ and the ‘Times’, had annual contracts initially with the Electric Telegraph Company and after 1865 with the combined telegraph companies for Press Passes. These were provided in books with tear-off slips that authorised the sender to transmit up to 200 words of news on account rather than for cash. The companies refused to extend this privilege to the hundreds of provincial newspapers as it would have been too open to fraud.

Press Passes on annual contract were also used by the sporting press in London: ‘Bell’s Life’, ‘Sporting Gazette’, ‘Sporting Life’, and ‘Sportsman’.

The passes were printed on different coloured stock for each newspaper and around six pass books were issued to each paper.

Sporting Intelligence comprised arrivals of horses, order of running, Tattersall’s betting, City betting, Manchester betting, latest betting and results of races. It cost subscribers, newspapers, news-rooms and individuals £25 per year, or £6 each for the winter quarters and £9 each for the summer quarters. In addition there was, throughout the 1860s, a Special Contract by which the “indefatigable” Benjamin Sutterby, the Company’s principal sporting news reporter, provided a half-column article each day at 10pm. In 1867 and 1868 he wrote for fourteen newspapers; the ‘Sporting Life’ and ‘Sportsman’ in London, the ‘Daily Post’ and ‘Gazette’ in Birmingham, the ‘Yorkshire Post’ in Leeds, the ‘Courier’, ‘Mercury, and ‘Post’ in Liverpool, the ‘Courier’, ‘Examiner’ and ‘Guardian’ in Manchester, the ‘Chronicle’ and ‘Journal’ in Newcastle and the ‘Daily Telegraph’ in Sheffield. For this he earned £400 a year.

There were two types of agreement for Special Wires in 1865. By one contract they were available from any of the three central stations of the combined telegraph companies between 7pm and 3 am. The companies provided the staff, messengers and stationery. For a circuit under 100 miles length the newspaper had to guarantee an annual expenditure of £400; for under 200 miles an income of £450 and above 200 miles, £500, to Ireland, including use of the underwater cables, £800. The rate charged on these wires was the tariff rate but with 60 words allowed instead of 20, and half-rate for every subsequent 30 words rather than 10 words.

In the other contract, for unlimited use of a Special Wire, the charges were: under 100 miles £600, under £200 miles £675, above 200 miles £750, and to Ireland £1,000.

The receipts of the Intelligence Department in 1865 from the Electric & International Telegraph Company’s general news contracts was £14,306, from the British & Irish Magnetic Telegraph Company’s contracts £9,494 and from Sporting Intelligence £6,000. Special Messages brought in a further £1,684. Their combined costs were £3,769 for collecting general news and £1,019 for sports.

In November 1868 the Intelligence Department was transmitting news to subscribers in: Aberdeen, for the ‘Free Press’, ‘Herald’, and ‘Journal’; Arbroath, ‘Guide’; Banff, ‘Journal’; Belfast, ‘Banner of Ulster’, ‘Morning News’, ‘Newsletter’, ‘Northern Whig’, ‘Northern Star’ and ‘Ulster Banner’; Birmingham, ‘Gazette’, ‘Journal & Daily Post’ and ‘Midland Counties Herald’; Bolton, ‘Chronicle’ and ‘Evening News’; Bradford, ‘Daily Telegraph’, ‘Observer’ and ‘Daily Times’; Bristol, ‘Daily Post & Mercury’, ‘Mirror & Times’ and ‘Western Daily Press’; Brighton, ‘Daily News’; Cardiff, ‘Cambrian Daily Leader’, and ‘Western Mail’; Clonmel, ‘Chronicle’; Cork, ‘Constitution’, ‘Examiner’, ‘Herald’ and ‘Reporter’; Darlington, ‘Times’; Doncaster, ‘Chronicle’ and ‘Gazette’; Dublin, ‘Daily Express’, ‘Evening Mail’, ‘Evening Post’, Freeman’s Journal’, ‘Irish Times’ and ‘Saunders’s Newsletter’; Dumfries, ‘Courier’, ‘Herald’ and ‘Standard’; Dundee, ‘Advertiser’ and ‘Courier & Argus’; Durham, ‘Advertiser’ and ‘Chronicle’; Edinburgh, ‘Daily Review’, ‘Evening Courant’ and ‘Scotsman’; Elgin, ‘Courant’ and ‘Courier’; Exeter, ‘Flying Post’, ‘Gazette’, ‘Weekly Times’ and ‘Western Times’; Glasgow, ‘Citizen’, ‘Daily Herald’, ‘Daily Mail’ and ‘Morning Journal & Evening Post’; Gloucester, ‘Citizen’; Hartlepool, ‘Mercury’ and ‘Herald’; Hereford, ‘Times’ and ‘Journal’; Hull, ‘Eastern Counties Herald & Hull News’, ‘Morning & Evening News’ and ‘Packet & Times’; Inverness, ‘Advertiser’ and ‘Courier’; Leeds, ‘Mercury’, ‘Times’, ‘West Riding Express’ and ‘Yorkshire Post’; Liverpool, ‘Albion’, ‘Courier’, ‘Dawn’, ‘Gore’s Advertiser’, ‘Journal & Daily Post’, ‘Mail’ and ‘Mercury’; London, ‘Daily News or Express’, ‘Daily Telegraph’, ‘Echo’, ‘Globe’, ‘Glowworm’, ‘Morning Advertiser’, ‘Morning Herald or Standard’, ‘The Star’, ‘Morning Post’, ‘Pall Mall Gazette’, ‘Shipping Gazette’ and ‘The Times’; Londonderry, ‘Guardian’, ‘Sentinel’, ‘Standard’ and ‘Journal’; Manchester, ‘Courier’, ‘Examiner & Times’ and ‘Guardian’; Newcastle, ‘Advertiser’, ‘Chronicle’, ‘Courant’, ‘Journal’, and ‘Northern Express’; Norwich, ‘Norwich Chronicle’, ‘Norwich News’ and ‘Norwich Mercury’; Nottingham, ‘Express’, ‘Guardian’ and ‘Journal’; Perth, ‘Advertiser’; Peterborough, ‘Advertiser’ and ‘Times’; Plymouth, ‘Western Counties Daily Herald’, ‘Western Daily Mercury & Journal’, ‘Western Morning News’ and ‘Western Daily Standard’; Preston, ‘Chronicle’, ‘Guardian’ and ‘Herald’; Sheffield, ‘Independent’ and ‘Telegraph’; Shields, ‘Daily News’ and ‘Gazette & Telegraph’; Shrewsbury, ‘Chronicle’ and ‘Journal’; Stafford, ‘Advertiser’; Stamford, ‘Mercury’; Sunderland, ‘Herald’ and ‘Times’; Taunton, ‘Herald’ and ‘Gazette’; Tralee, ‘Chronicle’ and ‘Kerry Post’; Worcester, ‘Herald’ and ‘Journal’; and York, ‘Gazette’ and ‘Herald’.

The telegraph office at all these places was kept open at night to receive news, whether daily or once or twice a week, dependent on the frequency of the paper.

Separately from the press, the Intelligence Department continued to provide information on annual contract to public and private news rooms in the provinces, for clubs, hotels, exchanges and institutes. These were each charged around £50 a year.

In 1868 the Electric Telegraph Company published its own view of the news combination:

“For many years the Electric & International Telegraph Company have had an ‘Intelligence Department’, to which a large and experienced staff of editors, reporters and others is attached, for the purpose of collecting home and foreign news, political, domestic and commercial, and distributing the same to every point at which such information can afford interest. The clubs in London receive, every half hour, intelligence of the general proceedings of Parliament. The provincial news-rooms and subscription-rooms, farmers’ ordinaries, and other circles, are supplied by telegraph with news of every occurrence which can affect their interests. A visit to any one of these political or commercial centres will illustrate at once the vast importance, as well as the immense public convenience of this organisation.”

“The ‘Intelligence Department’ of the Electric & International Telegraph Company has very varied duties to perform. Wherever there is any considerable gathering of individuals, whether for a permanent or a temporary purpose, the wires of the Company have to be placed in their midst, and special arrangements have to be made for the conveyance of the intelligence arising from the gathering.”

“If an agricultural meeting, a musical festival, or a Social Science Congress is held in any part of the United Kingdom, however distant, information of every day’s proceedings has to be collected and conveyed. If a public man of mark addresses his constituents or a public meeting, in any portion of the country, the words which fall from his lips have to be reported and telegraphed to the principal newspapers of the kingdom almost as soon as they are uttered.”

“At the present time it is certain that all this information, so important to the public and the world at large, with the greatest expedition, in the best and most comprehensive form, and at the lowest possible prices.”

According to William Hunt writing in 1887,

in ‘Then and Now, or Fifty Years of Newspaper Work’:

“At the time of the transfer of the

telegraphs to the Government, 168 papers used the telegraph services of the

companies, 59 dailies and 109 weeklies. Eight were using special wires, three

in Scotland and five in Ireland... The customers of the [Intelligence] Department

numbered 355 — newspapers, 168; literary institutions, 38; clubs, 33; exchanges

and chambers of commerce, 32: general merchants, 23; corn merchants, 19;

hotels, 18; share brokers, 12; banks, 3; Dublin Castle, 1.”

It was not until the anticipated demise

of the telegraph companies and their news departments during 1865 did the daily

provincial press in Britain manage to organise their own domestic

news-gathering and distribution service: the Press Association, whose name survives

today. This is surprising given that a flourishing Provincial Newspaper Society

had existed since 1836 and that there were several long-established commercial

agencies in London that collected foreign and metropolitan news, forwarding it

to newspapers by the Post Office mails in return for advertising space which

they sold on for cash to large-scale advertisers in the metropolis.

As might be expected the newspaper owners

forming the Press Association in 1865 soon fell to squabbling amongst themselves.

The Provincial Newspaper Society, representing the weekly papers, was happy

with the telegraph companies’ news services so were excluded from the new body.

More importantly only newspapers representing the “Liberal Interest” were represented

in the Press Association’s management. It had to be wound-up and a new, more

inclusive, Association created in 1868, grudgingly allowing the weeklies and

the Conservatives a voice.

Buying the Press

The Post Office was also conspiring with

the press owners with a systematic leaking of policy and promises over the

prospective appropriation of the telegraphs. William Hunt revealled in 1885 that their chief conspirator wrote “many

letters” secretly to provincial editors. As an example on April 6, 1868:

“I have been in communication with many

of your professional brethren on the matter to which you refer, and have told them

what I shall be prepared to recommend. It is as follows:

“1. That the newspapers shall appoint

their own collector or collectors of news (inasmuch as the Government

Department can hardly be expected to know the requirements of the press); and

“2. That we shall transmit the news thus

collected at rates which shall be sufficient to cover the cost of working.

“3. That our charges for special wires

shall be no more than enough to make the service self-supporting.

“4. That when the bill has become, or

seems likely to become, law, the newspaper proprietors shall appoint a small

committee to confer with me, and post me up as to the exact wants of each class

of paper.

“You will perceive that we can put

nothing of this in the bill. If we did we should be accused of bribing the

press, and should lose all the value of their support, but I have either spoken

or written in these terms to many of your brethren, and they have expressed

their satisfaction with my proposals.

“It is very desirable, however, that my

statements should only be mentioned privately and in strict confidence.”

Writing again on June 5, 1869, with details

of the highly confidential terms accepted by the Electric Telegraph Company,

the conspirator added:

“I shall be able, I hope, in a few days

to send you some more precise information, but if in the meanwhile you like to

use the substance of this letter I think you can do the measure good service. I

will ask you, however, in that case to put the case in your own words and not

to mention my name.”

The innovative and independent Intelligence Department, a “large and experienced staff of editors, reporters and others… for the purpose of collecting home and foreign news, political, domestic and commercial, and distributing the same to every point at which such information can afford interest”, was dissolved in 1870 at the instance of the Post Office.

Its manager, C V Boys, contrived to be both effective in business and a bon viveur. He was associated with the theatre, as well as horse racing, and supported newspaper and thespian charities. He negotiated a substantial pension from the government and received a testimonial in 1870 for his services to the Intelligence Department from his noble, journalist, acting and telegraphic friends consisting of a fine clock and a library of books. He was then age forty-five.

The Press Association ensured that the direct provision of information to public and private news-rooms – regarded as competitors – by the Post Office Telegraphs was prevented. When requested to service the rooms it quoted annual costs of £113 rather than the Intelligence Department’s £50. By these actions the Press Association, the creation of the leading critics of the telegraph companies, was established as a monopoly provider of news to the provinces and began its distribution service immediately afterwards using the Post Office Telegraphs, having been bribed with an incredibly cheap message rate that bore no relation to the costs; in London it used messengers.

There is no independent history of the Press Association and its secretive, subsidised news monopoly.

Only one of the existing commercial news-agents, William Saunders of 112 Strand, London, who had set up as a “stereotyping and general reporting agency” as recently as 1863 saw the opportunity that the telegraph offered and was willing to challenge the omnipotent Press Association in 1870. But it was not until November 1872 that the enterprising Saunders managed to separate his telegraphic news agency from the “hard-copy” distribution business as Central News, of 2 Telegraph Street, Moorgate, supplying articles and reports “to newspaper proprietors and to the managers of clubs, news-rooms and exchanges; also to private persons”. He took on many of the skilled writers and reporters of the Intelligence Department.

Reuter

I sing of one no pow’r

has trounced,

Whose place in every

strife is neuter,

Whose name is

sometimes mispronounced

As Rooter.

How oft, as through

the news we go,

When breakfast leaves

an hour to loiter,

We quite forget the

thanks we owe

To Reuter.

His web around the

globe is spun,

He is, indeed, the

world's exploiter:

‘Neath ocean, e’en,

the whispers run

Of Reuter.

‘St James’s Gazette’ 1859

Foreign News Agency

Julius Reuter developed the telegraphic foreign news-agency in London

from October 1851 onwards by means of a network of contacts on the

Continent of Europe. A German by birth and connexion, he gained

experience initially in selling twice-a-day foreign stock prices and

exchange rate information in printed circulars derived from telegraphic

and postal sources in Paris, Amsterdam, Berlin, Brussels, Vienna and

Athens to businesses in the ‘City’ of London from his two-room

“Continental Telegraph Office” at 1 Royal Exchange Buildings. He soon

realised the value of news.

His advertisement in the ‘Daily News’ , October 13, 1851,

the day before his office opened for business and a month before

the Submarine Telegraph to France was inaugurated

The Submarine Telegraph Company, then having a monopoly of European traffic, appointed J Reuter ‘General Agent for the Continent’ upon the opening to the public of their cable to France on November 13, 1851, to assist correspondents in sending and receiving messages. Despatches from foreign parts for London could be safely sent care of “Reuter Calais”.

Reuter opened “Continental Telegraph Offices” at Exchange Buildings in Liverpool in June 1852, and at Exchange Arcade Buildings, Manchester in July 1853, as well as at Calais in France and Ostend in Belgium, in careful concert with the arrival of the Submarine telegraph connection across the Channel to Europe. These offered quotation of funds and exchange, and prices of bullion from Amsterdam, Berlin, Frankfort, Hamburg, Madrid, Paris, Petersburg and Vienna. To these he added the latest prices and the state of the markets of corn, metals, colonial produce, silk, cotton, tallow, political news, &c., from Alexandria, Amsterdam, Antwerp, Bremen, Breslau, Calcutta, Danzig, Genoa, Hamburg, Königsberg, Leghorn, Odessa, Rio de Janeiro, St Petersburg, Stettin and Trieste.

Oddly, the Continental Telegraph Offices in Liverpool and Manchester were operated in Reuter’s birth name of ‘S Josaphat’. These offices prospered, providing British stock market and continental bourse data to newspapers and private subscribers, abandoning the Josaphat name at the end of 1854, finally adopting the Reuter instead of the “Continental Telegraph” by-line.

The Liverpool and Manchester offices were also providing foreign news by telegraph to several journals in the north of England and Scotland during 1854, well before Reuter was accepted by the London papers. The ‘Belfast Newsletter’, Edinburgh ‘Caledonian Mercury’, ‘Glasgow Herald’, ‘Leeds Mercury’, ‘Liverpool Mercury’, ‘Manchester Times’ and the ‘Preston Guardian’ all subscribed to Reuter’s earliest continental news service, benefiting from his German and Austrian contacts during the war in the Crimea.

The ‘Daily News’, a newly-established journal in London, originally edited by Charles Dickens, began to publish Reuter’s foreign market information, with the “Continental Telegraph” by-line in January 1855. The Submarine Telegraph Company furiously pointed out that it and the International company carried the information from Europe and that there was no such concern as the “Continental Telegraph”. The ‘Daily News’ ignored the complaint and continued to use the Continental by-line for Reuter’s economic data until 1858.

Initially rejected by the self-regarding attitude of the London press his business from 1852 until 1858 was primarily in the supply of mercantile intelligence and news of commercial value to private subscribers in the City of London for £8 8s per month. Reuter contracted all of his message business to the International Telegraph Company and their new cables to Holland in September 1853 in return for a modest discount. The International company shared his rooms in Royal Exchange Buildings for a couple of years, before merging with its parent, the Electric Telegraph Company. At the beginning of the following year he negotiated an additional rebate of 50% on the public rate for transmitting foreign news on their cables.

In addition to his mundane financial and mercantile bulletins for the commercial community in London, Reuter was providing the newspapers of Europe with telegraphic news from Britain, America and from all the distant places with which London, Liverpool and Glasgow traded.

|

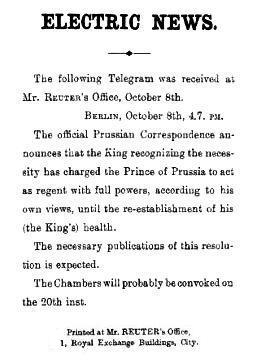

Reuter’s Telegram No 1

The news-slip

distributed to the London daily newspapers

on the evening

of October 8, 1858

But it was not until 1858 that Reuter was able to commence a trial scheme of foreign news telegrams over the public wires to the London press by offering a two-week free trial followed by £30 a month thereafter. On October 8, 1858 the ‘Morning Advertiser’, a daily newspaper published by the Licensed Victuallers and widely distributed in their public houses and inns, took Reuter’s first foreign news telegram; the other papers followed its example within days. The ‘Times’, joining with Reuter on October 13, was charged 2s 6d for twenty published words with a credit, or 5s 0d if no credit was given to Reuter. The other papers in London negotiated different rates, eventually on term rather than piece prices.

Reuter also sold news telegrams to the Electric Telegraph Company’s Intelligence Department for sending to the provinces, as well as selling them direct to the larger provincial papers with London offices.

During 1862 of the widely-circulated London papers, the ‘Times’ was paying £100 per month, the ‘Morning Herald’ and the ‘Daily Chronicle’ £83 6s 8d, the ‘Daily News’ £75, the ‘Daily Telegraph’ and the pioneering ‘Morning Advertiser’ £66 13s 4d, for Reuter’s foreign news messages.

The politics of 1860s, with countless wars in Europe, America and Asia, gave enormous impetus to news collection and hence to Reuter’s business. From 1859 he quickly established a pool for collecting and distributing international news with Havas in France, Wolff in Prussia, Stefani in Italy and Ritzau in Denmark.

In the papers Reuter’s

news messages were always called telegrams, introducing that word to

the public.

Reuter was one of the first users of the new Universal telegraph for internal

messages between his City offices in 1860 and by the mid-1860s was using it to

transmit foreign news over private wires to the offices of the major London

newspapers, replacing printed circulars and manifold (carbon) copies.

His firm had a day office at Royal Exchange Buildings, open from 10am to 6pm; a

night office at Finsbury Square, open from 6pm to 10am; and a West End office

at Waterloo Place, midway between the City and Parliament, all connected by

telegraph.

Already by 1861 the Waterloo Place office had its own wires provided by the Universal Private Telegraph Company, with instruments in the editor’s rooms of the main daily and evening newspapers in the Strand and Fleet Street supplying foreign news. The papers eventually included the ‘Daily News’, ‘Daily Telegraph’, ‘Echo’, ‘Globe’, ‘Morning Herald’, ‘Morning Post’, ‘Morning Star’, ‘Pall Mall Gazette’, ‘Standard’, ‘Sun’ and, of course, ‘The Times’. This office had thirty telegraph circuits in August 1861; eighteen for newspapers and for Reuter’s service use and twelve for the foreign ambassadors to London. It had its own private circuit to access the Electric Telegraph Company’s cables to the Continent. It was truly a communications “hub”.

Reuter promoted with C W Siemens the South-Western of Ireland Telegraph Company in 1863, to connect the city of Cork with Crookhaven, on the isolated southernmost point of Ireland, where metallic containers with news-messages were collected from the Cunard steamers from America. His news agency then promoted its own cable from Lowestoft to Norderney in Hanover, with connecting land lines in Germany, in 1865 as a speculation. He leased the public traffic rights to the Electric Telegraph Company.

When Reuter’s original contract with the combined telegraph companies’ Intelligence Department expired on January 1, 1865 he negotiated a new five year agreement. Under this he received £3,000 per annum, a substantial increase from the original £800, the companies having exclusive rights to sell and distribute his news telegrams to the provinces outside of a fifteen mile radius of Charing Cross in London.

In 1865 the news agency was incorporated as a joint-stock enterprise called Reuter’s Telegram Company. By this time he was charging each of his London newspapers an average of £1,000 a year for his foreign news.

Julius Reuter also

promoted and then became a director of the Société du Câble

Trans-Atlantique Français, an Anglo-French intercontinental telegraph, in

1867 so that his news agency might get priority access to American news-sources.

In 1869, as the telegraph companies were being appropriated, to maintain his

business Reuter contracted to provide the Press Association with foreign

telegrams for exclusive use in the British Isles outside London, and to

disseminate Press Association news overseas.

Reuter’s foreign news monopoly did not go unchallenged. The Telegraphic News Association, with a joint stock capital of £50,000, was established at 90 Cannon Street, London, on October 6, 1864. It began to circulate despatches from New York in January 1865, but ceased trading a month later. The Universal Telegram Company commenced with an even larger nominal capital of £100,000, at 4 Skinner’s Place, Size Lane, London, “conveying to or from all parts of the globe, news, intelligence, &c.,” on October 28, 1864. It, too, had a short life, such was Reuter’s strength.

It should be noted that the London newspaper press, the strongest critics of the telegraph companies’ news services, were very quick in adopting the Universal telegraph (q.v.) internally and on private wires between their editorial offices and their news-providers, such as Reuter. However their hostility to the companies by then was such that they were coy about admitting it – going to the length of censoring their titles from the Universal company’s newspaper advertising of its list of customers in 1860.

TELEGRAPHIC NEWS

|

Telegraph, from the Greek “tele”, distant, and “graphos”, writing